Introduction

Maritime infrastructure has become a cornerstone of national security, economic development, and energy independence for many developed coastal nations. This kind of infrastructure also has regional significance as it connects states’ energy systems, making such nations more resilient and competent. Nowhere is this situation more evident than in the Baltic Sea—a sea that has a semi-enclosed, quite narrow, and shallow continental shelf with unique environmental and geopolitical characteristics. An interesting part of this sea is the southern Baltic Sea. It is already witnessing a rapid expansion of offshore wind farms, cable and subsea pipeline connections as well as intensified maritime traffic, placing increasing pressure on already limited spatial resources. Consequently, the need for robust, intelligent security solutions is more urgent than ever. In this context, artificial intelligence (AI)-driven naval drone operations offer a revolutionary approach to enhancing the monitoring, surveillance, protection, and resilience of maritime infrastructure.

This study, first and foremost, defines the area of the southern Baltic Sea and determines the boundaries within which dynamic processes in maritime security are taking place. Subsequently, it attempts to characterise these ongoing processes or maritime operations. This will help illustrate the complexity and uniqueness of the region. The study also seeks to answer the question of what the main limitations to naval operations in the area are.

Furthermore, the study addresses the region’s energy potential and attempts to explain why the prospect of its exploitation is so appealing to the coastal states. Building on this, it focuses on both current threats and those likely to emerge in the near future. By investigating these challenges, the article analyses possible solutions through the central research question: Why and how would AI-driven naval drone operations improve maritime security, and in which areas would they perform best?

It is important to acknowledge that this research faces certain limitations, primarily due to the relatively low saturation of the maritime domain with unmanned systems and the fact that AI-based systems for managing maritime information—or, more broadly, maritime operations—remain largely in the conceptual phase.

This study adopts a qualitative analytical approach, grounded in the review of relevant literature, official reports, and statistical data from a variety of international and academic sources. The research process involves the analysis of the existing materials to identify key patterns and trends related to maritime infrastructure and security in the southern Baltic Sea. Through inference, the study aims to draw reasoned conclusions from the available data, particularly where direct evidence was limited due to the emerging nature of the subject matter. The findings were integrated through a synthesis of knowledge, which involved combining operational and vast maritime experience, knowledge of nautical charts, and insights from diverse sources to construct a coherent understanding of how technological advancements and evolving geopolitical factors are shaping the regional maritime security landscape. Finally, the focus was placed on identifying and understanding the current dynamics and emerging challenges associated with maritime infrastructure and security in the southern Baltic Sea.

The research process began with a spatial, geographical, and operational characterisation of the southern Baltic Sea. This included analysing geographical and environmental features, such as seabed topography and maritime traffic patterns, using open-access scientific studies and spatial datasets, notably those related to vessel tracking (Hakola, 2020) and marine protected areas (Drzycimski, 2000). These sources provided the foundation for delineating the operational environment based on maritime activities. The next phase involved assessing the status and developmental trends of critical offshore infrastructure—including offshore wind farms, pipelines, undersea cables, and nuclear energy facilities. This required the examination of sector-specific data from both regional and European institutions as well as corporate and policy reports detailing the scale and direction of current and planned investments. To analyse security aspects, the study relied heavily on recent expert analyses, including reports from the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats, Hybrid Centre of Excellence, and the Estonian Academy of Security Sciences. These sources provided valuable insights into the growing threat landscape—including hybrid and cyber threats—and established cornerstones of legal and strategic challenges in protecting transboundary infrastructure. Furthermore, the study incorporated theoretical and conceptual sources (e.g. Pająk, 2024; Sari, 2025), reflecting the current state of research and early-stage application of autonomous systems in maritime operations. Although practical deployment is still limited, these analyses helped identify the most promising areas where AI-driven drones may be effective, such as real-time surveillance, threat detection, and infrastructure monitoring.

A key criterion in source selection was recency. Given the rapid evolution of maritime security challenges and technological advancements, particular effort was made to ensure that all data and literature used were current and relevant—most sources date from 2020 to 2025. This up-to-date information was critical for providing an accurate assessment of the current situation and for projecting near-future developments. It is worth underlining that the interdisciplinary nature of the topic required the integration of materials from multiple domains, including security studies, maritime law, environmental science, and energy policy, reflecting the complex and interconnected nature of maritime infrastructure governance in the Baltic Sea region.

The Southern Baltic

The Baltic Sea is a complex region, and its borders are not always obvious. The very basic division of the Baltic Sea is based on the S-23 publication, a technical document by the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO, 1953), titled Limits of oceans and seas. In its third edition, S-23 publication defines three subdivisions within the Baltic Sea: the Gulf of Bothnia, the Gulf of Finland, and the Gulf of Riga. While not officially named in the publication, the remaining central water body is commonly referred to as the Baltic Proper (Jakobsson et al., 2019, p. 905). Consequently, the Baltic Proper itself is considered the middle part of the Baltic Sea, forming the biggest open part of it. In addition, the Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission (HELCOM, 2018) subdivided the sea into seventeen sub-basins based on salinity gradient and biological features. Although this classification extends the Baltic Sea to include the Kattegat and Skagerrak, it does not provide a clear geographical division within the Baltic Proper itself. The southern Baltic Sea refers to the southernmost part of the Baltic Sea. It encompasses key basins and bays, such as the Arkona Basin, Bornholm Basin, Bay of Mecklenburg, and Bay of Gdańsk, which are integral parts of the Baltic Proper. Although there is no clearly defined western border of the southern Baltic Sea, it may be assumed that the Fehmarn Belt is included, whereas the Bay of Kiel is usually not considered a part of the southern Baltic Sea, but rather a southwestern part. In the west, this maritime region is surrounded by the Danish islands of Lolland, Falster, and Zealand and in the north by the Swedish regions Skåne and Blekinge and the Kalmar County.

A latitudinal line joining the Swedish island of Oland in the west and the border between Lithuania and Latvia in the east is usually considered as the northern border of the southern Baltic Sea. Although this line is also not defined, most relevant publications indicate that the Gotland Basin is not a part of the southern Baltic Sea. This approach is also enshrined in the European Union (EU)-cofounded Interreg South Baltic Programme 2021–2027 (Figure 1).

In the east, the southern Baltic Sea is surrounded by Lithuania and Kaliningrad Oblast. Finally, in the south, it is surrounded by Warmińsko-Mazurskie, Pomeranian, West Pomeranian Voivodeships, and the German region of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.

The southern Baltic Sea is characterised by its shallow waters, including four main shoals: Oder, Bornholm,Slupsk, and Mid Baltic. The shoals have depths of between 6 and 20 m. The last is split between the Polish and Swedish exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and separates the so-called “southern basin” from the rest of the Baltic Proper.

Characteristics of the southern Baltic Sea in terms of maritime operations

The Slupsk Furrow (Drzycimski, 2000) plays a key role as the deepest connection between the Gotland Basin and the Bornholm Basin, separating the Central Bank from the Slupsk Bank. The furrow has a depth range of 65 m (in the western part) to 95 m (in the eastern part), ;consequently it offers only a limited water exchange with the North Sea through the shallow Danish Straits. Nevertheless, the southern Baltic Sea is the first in line to enjoy salty water that is rich in oxygen from the North Sea when an exchange happens. Such an influx of heavy salty water creates an additional layer of water (salty and heavy), spreading at the bottom. This periodic salty water layer further complicates the already very complex patterns of propagation of sound in the seawater. It increases the difficulty in predicting the pattern at a specific time and also makes underwater detection of objects much more complicated. Finally, under certain conditions, detection range could be reduced.

It is also worth underlining that this specific area has a very limited number of islands. Apart from Bornholm, which is situated at almost the centre of this area, there are merely three in the south, situated near the coast of western Poland and Germany, namely Wolin, Usedom (Uznam), and Rugen as well as a few small but rocky ones near the coast of Swedish Blekinge County. In addition, it needs to be mentioned that the southern coast is mostly sandy, an effect of the last glacier, whereas the northern one, except Scania, is rather rocky with a few sandy beaches.

Next, the influence of numerous rivers discharging freshwater into the Baltic Sea must be considered. This influx significantly reduces salinity—Baltic Sea water averages around 7–8%—and forms a surface layer with the lowest salinity (Stockmayer and Lehmann, 2023, pp. 466–483). Additionally, the high load of nutrients from these rivers accelerates eutrophication. As a result, the Baltic Sea, which is typically turbid, often turns green or brown during certain seasons, reducing visibility to just a few decimetres. This limited visibility can enhance the concealment of underwater operations, as it prevents the detection of submerged objects by aerial or even satellite observation.

Finally, the seasonal variability of the conditions in the Baltic Sea must be taken into account. In winter, for example, the water could be relatively clean and free of algae, and the speed of propagation of sound throughout the entire depth of the water remains relatively the same, producing the longest detection range and leaving no hiding place for submerged objects. However, sometimes in winter, a contrary scenario may emerge; the conditions could change dramatically if the sea freezes or is covered with drifting ice. Although the southern Baltic Sea typically remains ice-free, significant portions may freeze in particularly harsh winters, such as those of 1986–1987 and 2010–2011. In rare instances, the entire Baltic Sea can become frozen, for example during the winter of 1946–1947. Nevertheless, shallow areas in the northern and eastern parts of the Baltic Sea usually freeze during cold winters and during extended periods of deep frost; large sections of the sea may even become ice-covered. However, with the ongoing climate change, ice coverage in the southern Baltic Sea is becoming increasingly rare, and in some recent winters, even large bays that traditionally froze remained ice-free. It is worth mentioning that two extreme events occurred within the last decade in the Baltic Sea. The winter of 2015 was exceptionally mild, with the maximum ice extent reaching just 51,000 km2—the lowest value recorded since the beginning of the time series in 1720. However, only 5 years later, in the winter of 2020, the situation intensified further, with ice coverage dropping to just 37,000 km2—setting a new record low (HELCOM, 2023). Both drifting ice and frozen sea make the detection of underwater objects more difficult as well as render underwater operations themselves quite complicated. In spring, the surface layer of the water heats up and creates the perfect condition for algae to bloom. Consequently, catalysed by the nutrients brought by the rivers, the algae population explodes and the water could turn green or even brown, reducing the visibility significantly. In such circumstances, visual detection is not possible.

The Baltic Sea presents a very unique environment for underwater operations. On the one hand, its limited depths constrain the manoeuvrability of submerged submarines. With an average depth of just 50 m (Jakobsson et al., 2019, p. 921), not many areas of the Baltic Sea are suitable for conventional underwater operations. In fact, most areas with depths lower than 30–50 meters are not considered suitable for such operations at all (MXP-1(D), 2002, pp. 2–11). As a result, large parts of the Baltic Sea are unsuitable for conventional submarines. In particular, the Baltic Sea is generally considered a no-go zone for nuclear-powered submarines, which require deeper waters and more open space to fully exploit their advantages in speed and virtually unlimited power provided by a nuclear reactor (MXP-1(D), 2002, pp. 2–15). On the other hand, the shallow continental shelf limits the effectiveness of various antisubmarine detection systems. Many types of towed sonar arrays and even torpedoes require a minimum water depth to function properly (Colin, 2011), rendering them ineffective in large areas of the Baltic Sea. The inability to use towed sonars, which are usually most effective, makes anti-submarine forces resort to hull-mounted sonars or variable-depth sonars, deployed either from ships or helicopters.

To make matters more complex, the conditions of underwater operations in the Baltic Sea vary with the seasons (Klusek and Lisimenka, 2016). For example, during winter, the acoustic conditions of underwater operations are generally unfavourable. Sound tends to propagate uniformly through the water column, making it extremely difficult for submarines or other submerged objects to remain concealed (Trzciniak-1, 1978, p. 40). In contrast, during spring, summer, and autumn, the formation of both haloclines and thermoclines can lead to alternating layers within the water column where the sound speed profile fluctuates, periodically increasing and decreasing with depth. These layers can create acoustic shadow zones and affect sonar performance. However, such conditions are often unpredictable and difficult to model with precision. While some patterns are observable, there are no fixed rules, as local conditions and sudden weather changes can be decisive (Grelowska, 2016, pp. 27-28). For example, prolonged winds from a single direction can push the surface layer of water towards one shore and cause deep water to rise to the surface. This phenomenon is known as a seiche and affects local patterns of sound propagation in the water.

The unique environmental characteristics of the southern Baltic Sea, including its shallow depths, complex seabed topography, high maritime traffic density, and seasonal low predictability, present significant challenges for conventional manned underwater operations. However, these very conditions also create a compelling case for the deployment of unmanned systems, particularly naval drones (Liu et al., 2016). Their smaller size, adaptability, and, most of all, lower operational risk make them well suited to navigate and operate in this constrained and dynamic maritime space. As such, the region’s operational environment not only complicates traditional approaches but also supports the development and integration of drone-based solutions. Overall, it reinforces the broader argument about the operational necessity of unmanned capabilities, especially in shallow seas, such as the Baltic Sea.

The energy potential of the southern Baltic Sea

The southern Baltic Sea area holds significant promise for renewable energy development, particularly offshore wind energy. Its unique geographical conditions render it a strategic area for advancing Europe’s energy transition. In favourable circumstances, it could enhance regional energy security.

The region’s shallow waters, many shoals, consistent wind patterns and speeds (Olczak and Surma, 2023), as well as proximity to energy-demand centres (big agglomerations on the shores), create almost ideal conditions for wind farm development. In this context, it is important to note that several big energy-demanding cities are situated on the shores of the Baltic Sea. Among them are St. Petersburg (over 5.5 million citizens) (Interfax, 2022), Stockholm (almost 1 million), Helsinki (almost 0.7 million), Copenhagen (0.6 million), Goteborg (0.6 million), Riga (0.6 million), Gdansk (almost 0.5 million), Kaliningrad (almost 0.5 million), Tallin (over 0.45 million), Szczecin (almost 0.4 million), Gdynia (0.25 million), and Rostock (0.2 million) (Eurostat, 2025b). All of these cities are a basis for maritime industries, including the shipbuilding industry and other heavy industries, which are especially energy-consuming. It is noteworthy that only a few of these cities are located near a nuclear power plant, which could serve as a significant source of energy (including St. Petersburg, Helsinki, Stockholm, and Goteborg). Having that in mind, it is also important to point out that almost all of them, except a few situated by narrow passages or bays (such as St. Petersburg), have favourable conditions for expanding energy production from renewable sources, especially wind.

Estimates indicate that the total offshore wind potential of the Baltic Sea could reach 60 GW by 2030 and soar to 300 GW by 2050, with the southern regions alone potentially contributing up to 450 GW (European Commission, 2023). This figure is approximately forty-five times greater than the combined output of all the following nuclear power plants: Loviisa Nuclear Power Plant, with two reactors of about 507 MW each (Fortum, 2025); Forsmark Nuclear Power Plant, with three reactors: Forsmark 1 about 1,025 MW, Forsmark 2 about 1,038 MW, and Forsmark 3 about 1,212 MW (flexRISK, 2013); Ringhals Nuclear Power Plant, with two reactors: Ringhals 3 about 1,074 MW and Ringhals 4 about 1,130 MW (Vattenfall, 2025); and Leningrad Nuclear Power Plant, with two RBMK-1000 reactors of about 925 MW each as well as two VVER-1200 reactors of 1,195 MW each (NS Energy, 2020). With inter-Baltic energy connections enabling bidirectional energy transfer, this wind potential will not only be sufficient to meet future energy demands but will also significantly bolster the green energy transition.

Although Denmark and Germany are currently at the forefront of the European maritime energy sector, the Polish, Danish and Swedish EEZs offer particularly favourable sites due to more favourable depths, accessibility, higher market values, and fair wind conditions.

Technological impact on spatial security challenges

The southern Baltic Sea’s evolving maritime landscape presents a dual challenge: safeguarding critical infrastructure while managing complex spatial constraints. Traditional surveillance and security measures—reliant on manned patrols, radar, and static sensors—struggle to provide comprehensive, continuous coverage in the situation of a growing presence of infrastructure at sea. As much infrastructure is planned for the southern Baltic Sea, the area is going to become geographically congested. An example of the planned infrastructure is offshore wind farms, which are often located in distant areas in vast EEZs and cover big maritime areas. Other examples are subsea pipelines and cables, which connect electrical, gas, and telecommunication systems on opposite shores of the southern Baltic Sea or connect maritime infrastructure, such as oil rigs and wind farms, with onshore parts of their systems.

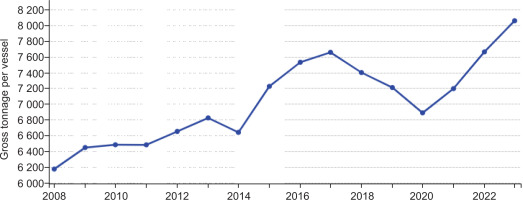

Beyond these, the southern Baltic Sea is experiencing a growing maritime traffic. In 2023, a 3.6% increase was observed in the number of International Maritime Organisation (IMO)-registered vessels operating in the Baltic Sea (Jalkanen et al., 2024, p. 2). In 2024, the year-on-year increase in the number of ships exceeded 4.5% (Bartosiewicz et al., 2024). Not only are there more ships transporting more cargo each year but also the ships themselves are becoming bigger (Figure 2). For example, between 2012 and 2020, the average container ship size in the Baltic Sea grew from 1,342 TEU to 1,903 TEU—an increase of 42% (Kerbiriou, 2024, p. 213). This trend reflects global developments in the shipping industry, where economies of scale and efficiency drive the deployment of increasingly larger vessels. For example, since 2006, the average container ship has doubled in size, reaching 4,580 TEU in 2024 and is expected to exceed 5,000 TEU in 2025 (Baltic and International Maritime Council [BIMCO], 2024). This reflects an average annual growth rate of approximately 5.5% in ship size over the 19-year period. What is particularly interesting is that ships with a capacity of more than 12,000 TEU have accounted for 51% of fleet’s capacity expansion (Marine Link, 2024). This trend is reflected in the growing size of average ships calling at main EU ports.

Figure 2

Average size of vessels calling at main ports, EU, 2008–2023. Note: Main ports are ports handling more than one million tonnes of goods or 200,000 passengers annually. Data is based on inward declarations. Break in time series from 2015 due to methodological improvement in the data reported by the Netherlands. Source: Eurostat (2025a).

The southern Baltic Sea is experiencing a significant and continuous increase in maritime traffic, both in terms of the number of vessels and the volume of cargo being transported. Nevertheless, maritime traffic lanes remain mostly unchanged. Most of the traffic goes through the Baltic Straights to the North Sea and Atlantic Ocean or from that area to the biggest Baltic ports. Almost all the incoming or outgoing ships move via the southern Baltic Sea. Maritime spatial plans take traditional shipping lanes into account, but in many cases the planned infrastructure is very close to the lanes. All the above issues contribute to greater pressures on the maritime space.

As maritime transport continues to grow, the spatial and environmental challenges in the southern Baltic Sea become more pronounced, raising concerns about safety, environmental sustainability, and long-term spatial planning. It is important to highlight that the Baltic Sea, due to its unique ecological characteristics and semi-enclosed nature, is designated as a Sulphur Emission Control Area (SECA). This imposes stricter environmental regulations on ships operating within the region, particularly regarding the allowable sulphur content in marine fuels. While such regulations are crucial for reducing air pollution and protecting marine ecosystems, they also place additional operational and economic demands on maritime transport operators, which may influence traffic patterns and ship routing decisions.

Despite the changing dynamics of vessel size, environmental requirements, and traffic volume, the maritime traffic lanes in the southern Baltic Sea have remained largely unchanged over the past decades (Figure 3). The majority of vessel movement continues to concentrate along traditional shipping routes that go through the Baltic Straits (mainly Sund or Great Belt) to the major Baltic ports. The main shipping lanes traverse the northern section of the southern Baltic Sea and diverge south of Gotland into the eastern and northern routes. The first one leads to ports in either the Gulf of Finland (Russian: Petersburg, Primorsk, and Ust-Luga, or Finnish: Hamina-Kotka and Helsinki, or Tallinn in Estonia) or the Gulf of Riga. The northern lane leads to the Sea and the Gulf of Bothnia (e.g. ports of Kokkola, Lulea, Pori, Rauma, Vaasa, etc.) as well as to Swedish ports in the central Baltic Sea (e.g. Stockholm). Besides, local lanes connect the Baltic Straits to the ports of Gdynia and Gdansk, Kaliningrad, Klaipeda and Świnoujście-Szczecin. In addition, the southern Baltic Sea is crossed by a few important local shipping lanes connecting ports on both sides of the Baltic Sea (e.g. Gdynia–Karlskrona, Trelleborgto Świnoujście, Klajpeda, Lubeka (Ivendorf), and Rostock; Rostock–Gedser, Lipawa–Lubeka, Ystad–Świnoujście, and Rone to Koge, Sassnitz, and Ystad). All of them are traversed by passenger ferries and/or roll-on/roll-off ships.

Based on earlier discussion, it needs to be highlighted that seas can no longer be considered as areas for shipping only. Maritime areas have a number of usages that can benefit not only humanity but also the environment. There are at least eleven functions of maritime areas (Pająk, 2019, pp. 166–167), including energy generation, transportation, exploitation of natural resources, military practices, environmental protection, and preservation of submerged heritage. Some of the functions can exist simultaneously, while others cannot.

Therefore, maritime (or Marine) spatial planning (MSP) has emerged as a strategic tool to manage and coordinate the various uses of maritime space, ensuring that economic development is balanced with environmental protection and maritime safety. In essence, MSP is “about managing the distribution of human activities in space and time to achieve ecological, economic, and social objectives and outcomes.” In this regard, it is both a political and social process (Ehler et al., 2019, p. 1). Meanwhile, as the demand for marine space (with different uses and activities) increases, MSP becomes a process for managing the marine environment under growing human demands. Most maritime spatial plans in the Baltic region acknowledge and incorporate traditional shipping lanes as a fundamental layer of spatial organisation. However, there is a growing concern that the proposed locations of some planned infrastructural developments—such as offshore wind farms, underwater cables, and aquaculture zones—are in relatively close proximity to these established routes. This spatial proximity raises potential risks, including navigational hazards, reduced manoeuvring space for large vessels, increased likelihood of maritime accidents and conflicts between maritime functions.

As maritime transportation, so far, remains the most important function of the sea, MSP frameworks continue to give priority to shipping routes. Meanwhile, maritime trends, including the growth in ship size and volume, environmental constraints, and the need for secure and efficient navigational corridors, will put additional pressure on existing and planned infrastructure. As the demand for clean, renewable energy continues to grow (International Energy Agency [IEA], 2025, p. 3), maritime areas are set to play an increasingly vital role in meeting future energy needs. Consequently, coastal nations would experience a boom in the number of wind farms and other sources of renewable energy at sea, such as floating photovoltaics (Pająk, 2023, pp. 189–203) and buoys generating energy from wave movement.

To ensure harmony and, more importantly, safety while utilising the sea for various maritime functions, a proactive and adaptive approach to MSP, data collection, and sharing is critical, since technological development not only brought new possibilities of maritime area utilisation but also new threats.

Threats—both longstanding and newly emerging on the horizon

Although the Baltic Sea enjoyed a long period of relative calm in terms of maritime security and infrastructure, recent events have changed that situation. A series of attacks and suspicious incidents that resulted in damage to critical underwater maritime infrastructure have made it necessary to reassess security issues in the Baltic Sea. It is noteworthy that since the onset of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, several such events have occurred. First, the Nord Stream 1 and 2 gas pipelines were damaged (26 September 2022). Next, the Baltic connector cable was damaged by the ship Newnew Polar Bear (8 October 2023). A year later, the cables between Germany and Finland (BCS East-West Interlink and C-Lion) as well as between Sweden and Lithuania were damaged by Yi Peng 3 (18 November 2024). Shortly after that, the Estlink 2 power cable connecting Finland and Estonia was damaged by the vessel Eagle S. (25 December 2024). In addition, the fibre optic cable connecting Latvia and Gotland was damaged by the bulk carrier Vezhen (26 January 2025). Some of the cases mentioned above are connected with the so-called Russian “shadow fleet”. “Shadow fleet activities are (war-) economically motivated but come with political and diplomatic leverage” (Uusipaavalniemi and Juha-Anterko, 2025, p. 7). Since merchant ships are engaged in damaging the infrastructure of other states, the incidents shall be, without any doubt, identified as clear examples of hybrid warfare.

A characteristic of hybrid warfare is that it is very difficult to attribute responsibility for the damage caused and to distinguish it from accidental or unintentional actions. In addition, the zonal logic of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) convention makes it particularly difficult for coastal state authorities to safeguard critical underwater infrastructure against hybrid threats (Sari, 2025, p. 20). Consequently, infrastructure located in international waters is within a legal grey area, which makes it susceptible to hybrid warfare attacks (Muuga et al., 2025). However, the extension of these systems beyond territorial waters does not render them legitimate targets, and any effort to damage such infrastructure should be deemed unlawful.

In the Baltic Sea, much of the critical underwater infrastructure is situated along deeps or rather deeper parts of this shallow sea, often located beyond territorial waters, within the EEZs but relatively far from the coast. The considerable distance from shore and the legal status of international waters—ensuring freedom of navigation—increase their vulnerability to hybrid threats. Moreover, much of this infrastructure is transboundary in nature, as pipelines, and power and telecommunication cables are usually operated by multiple entities from different countries (Miętkiewicz, 2025, pp. 55–57).

At sea, protecting critical underwater infrastructure becomes nearly impossible due to the low density of patrols and the significant influence of weather on maritime accidents. An important contributing factor is the blurred responsibility among the shipowner, operator, charterer, insurer, captain, and crew as well as the fragmented ownership spread across multiple companies. Beyond that, the existence of flags of convenience not only allows for reduced operating costs of vessels but also lowers the requirements of technical maintenance standards, crew training and experience as well as the scope and level of insurance coverage. As a result, a significant portion of vessels operating on the world’s seas may potentially pose a threat to critical maritime infrastructure.

Countering hybrid threats to critical underwater infrastructure at sea is very challenging as protection of maritime cables is embedded not only in maritime and cyber security policies but is also connected to ocean governance as well as digital and infrastructure policies (Bueger et al., 2022, p. 40). Consequently, an efficient approach must include not only robust foreign, defence, and security policies but also a comprehensive development policy and international cooperation across various levels and within multiple organisations, not limited to maritime ones. This approach is difficult to implement if one of the Baltic states deliberately undermines these efforts and exploits loopholes in UNCLOS, such as grey zones and flags of convenience. The situation deteriorates if such a state occupies two locations in the Baltic Sea, which not only broadens the range of potential threats but also provides a constant convenient pretext for conducting maritime shipping between both of them.

Meanwhile, the emergence of maritime drones introduces an entirely new dimension to the creation of threats and the potential for damaging maritime infrastructure. While it is already difficult to assign responsibility for incidents at sea, it becomes significantly more challenging in the case of maritime drones, which are by definition unmanned, not subject to international conventions, and lack crew members.

The use of drones significantly broadens the range of hybrid and full covert attack scenarios, where identifying the perpetrator is extremely difficult. This will undoubtedly offer new opportunities not only to terrorist groups but also—and perhaps most importantly—to states hostile to the collective West, seeking to undermine the global order that largely depends on maritime trade and naval power. A natural candidate in this regard is Russia, a Baltic state with access to the sea in two areas, the first in the Gulf of Finland and the second in the southern Baltic Sea.

Solutions to hybrid threats

Unmanned maritime vehicles, sometimes referred to as aquatic drones (Anderson et al., 2023, pp. 1–7), and more commonly known as maritime drones, constitute a robust and rapidly growing set of capabilities. Principally, these platforms could be divided into subgroups. The very basic subdivision relies on the environment the vehicles operate in: either on the surface of the sea (unmanned surface vehicles [USVs] or beneath it (unmanned underwater vehicles [UUVs]). The latter could be divided into remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) (Pająk, 2024, p. 10). In addition, some research articles add biomimetic vehicles to the UUV group (Miętkiewicz, 2023, pp. 22–23). Recently, a new group of unmanned maritime vehicles that are able to operate in more than one domain emerged—unmanned hybrid vehicles. This group usually consists of hybrid aerial–underwater vehicles (HAUVs) (Qi et al., 2025, p. 667) and hybrid surface–underwater vehicles (HSUVs) (Jin et al., 2020, pp. 475–476). Nevertheless, the key term that is reshaping the field is the autonomous system. Here, autonomy is described as “designed and verified to emphasise the need for formal approval of the automation system to operate without human supervision or control” (Rodseth et al., 2022, p. 012018) for a long period. Meanwhile, it seems that the advancement of AI and its integration into maritime vehicles have significantly enhanced the scope and effectiveness of autonomy.

Autonomous naval drones equipped with sophisticated programmes, not even AI, offer a scalable and adaptive solution that can counter old and emerging threats. These platforms can operate not only independently but also in swarms (groups), navigating shallow waters, tight corridors, and adverse conditions with precision. The relatively small size of autonomous naval drones enables them to navigate freely among natural barriers, such as small islands or skerries, and between artificial structures, including oil rigs and wind farms. Due to their low weight and compact dimensions, USVs are highly manoeuvrable and readily deployable in shallow environments—including rivers and coastal areas—where larger craft face operational limitations (Liu et al., 2016). This great freedom to manoeuvre is far beyond those of conventional ships, not to mention submarines. Moreover, artificial or small natural islands, usually considered as navigational threats for ships, could serve as support sites or supply bases for drones in terms of charging batteries, maintenance, data exchange points, and even spare parts depots. Confined areas usually offer very limited spaces in terms of navigation for conventional forces, especially underwater, as the relatively big size of conventional vessels renders manoeuvrability in congested areas rather impossible. Meanwhile, technological advancement allows drones to better manoeuvre in such areas. Also, due to such advancement, it is now possible to make drones smaller and more capable as well as expand their endurance and range. As a result of their small size and weight, it is easy to integrate drones with conventional forces.

It is of utmost importance to highlight that drones possess one more crucial advantage:they can accept greater risks (Pająk, 2024, p. 75); such risks would normally not be accepted in terms of conventional operations. This is due to their relatively low price, greater number and lack of personnel that could be put in a distress situation. Moreover, the development of adaptive autonomy has enabled maritime drones to operate effectively in dynamic and unpredictable environments by adjusting missions in response to changing conditions, whether managing emergencies, tracking moving targets, or complying with regulations and environmental requirements (Kale, 2023, p. 598). Each of these capabilities represents a significant advantage. Consequently, maritime drones are becoming more and more present in many types of operations, even those that were traditionally considered too risky or ineffective for surface combatants and submarines.

It is widely acknowledged that maritime drones are subject to certain limitations. Their relatively small size reduces detection range, both directly (as a result of low height) and indirectly (as a result of the need to reduce the size of devices). Their small size also makes them vulnerable to weather conditions, which could affect the effectiveness of elecro-optical sensors in harsh seas (Prasad et al., 2016). Also, managing dynamic environments, such as vessels, obstacles, and waves, poses significant challenges for maritime drones and swarms, as path planning and formation control are computationally complex and coordination-intensive, and the existing algorithms often fail to generalise effectively (Liu et al., 2024, pp. 992–1003). Drone-assisted mobile communications hold significant promise but remain in its early stages, facing critical challenges, such as enabling seamless wide-area coverage through high-speed, low-latency integration with heterogeneous airspace networks, and addressing the security risks inherent in wireless transmission, particularly for maritime drones vulnerable to eavesdropping, interception, and channel estimation attacks (Wang et al., 2023). Also, for now, drones are somewhat limited in endurance (up to 72 hours of operations in terms of medium autonomous naval drones, using HUGIN as an example; Naval technology, 2019) and range (about 200–250 nautical miles for underwater autonomous vehicles to 500–800 for surface autonomous drones, using combat-proven Magura surface drone as an example; Hatton, 2024). However, larger units are being constructed with greater autonomy and range.

Artificial intelligence possesses capabilities that could make drone operations even more effective. This is mainly due to real-time threat detection and mitigation (Paulraj et al., 2025) and the ability to react strictly in line with a protocol. AI is also capable of predictive pattern analysis and autonomous decision-making (Unlap, 2024). All these features empower drones to detect anomalies, track unauthorised activities, and respond rapidly to both physical and cyber threats.

However, deploying such systems in the southern Baltic Sea also raises challenges. These include securing global positioning system (GPS) signal, navigation of unmanned maritime systems (Omitola et al., 2018) as well as communication networks against jamming, ensuring safe coordination among multiple autonomous agents, and integrating drone operations into civilian maritime traffic systems without disruption. Addressing these issues requires not only technological innovation but also coordinated policy frameworks, cross-border collaboration, and investment in AI-specific maritime infrastructure.

Operational use cases in the Southern Baltic Sea

Maritime drones in the southern Baltic Sea could be employed as versatile Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) assets, with USVs acting as relocatable, sensor-equipped platforms—potentially hosting UAVs—for persistent monitoring and rapid detection of hostile activities in order to counter disinformation and enable timely responses. Meanwhile, UUVs would surveil undersea infrastructure for tampering and, together with other sensors, provide a layered defence against underwater intrusions (Savitz, 2024, p. 15). The deployment of AI-driven naval drones in the southern Baltic Sea would enable a wide range of operational use cases tailored to the region’s unique challenges. One primary application is the protection of offshore wind farms, and subsea cables and pipelines, which are rapidly expanding as part of national energy strategies. Drones equipped with AI can conduct continuous monitoring of maritime infrastructure, detect unauthorised vessels, and identify anomalies, such as dropped objects or potential sabotage attempts. This will lead to increased efficiency as the frequency of patrol will increase. In distant maritime areas, it would be necessary to utilise a large number of unmanned vehicles and provide bases for maritime drones.

Another key use case is harbour and port security. Given the region’s quite dense maritime traffic, concentrated along main sea lines of communication and narrow straits, road steads, anchorage areas, and port entrances, it is observed that certain regions are very vulnerable. In most of these areas, naval drones, even with medium range and autonomy, can perform regular monitoring and patrols. Moreover, autonomous drones with short range and very limited autonomy can perform high-frequency inspections of harbour basins, coastal underwater infrastructure, and even hulls in ports or, sometimes, in anchorages. Maritime unmanned systems can support security, customs, freight and anti-trafficking operations without seriously disrupting port workflows. Finally, AI-based video and sonar analytics would allow for early detection of divers, hostile unmanned vehicles, and suspicious objects, enabling a pre-emptive, quick response by dedicated forces.

It is not without significance that drones can also play a vital role in search and rescue operations (Queralta et al., 2020, pp. 1–6) and environmental monitoring. Drones, as vehicles with buoyancy, can be used in emergency situations to assist a person in water, possibly giving them a life jacket and an individual survival kit. In coastal waters, AI-enabled autonomous maritime systems can also be used to detect oil spills (Moursi et al., 2025) and monitor marine litter (Escobar-Sánchez et al., 2022). In addition, such systems can also be used to detect sediment pollution (Bojke et al., 2024, p. 252) and dead fish floating on the surface (Fernandez-Figueroa et al., 2025, p. 482). Underwater vehicles can be used to observe sediment displacement and even to analyse the basic parameters of water in the sea. Certainly, an increased density of vehicles measuring the propagation of sound in the water would help to provide more data in order to better predict patterns in this dynamic environment. These uses of drones contribute to broader maritime situational awareness.

It is important to acknowledge that ensuring maritime security, especially for infrastructure, requires the daily deployment of multiple drones. While current operators can manage a handful of drones simultaneously, scaling up to dozens, or even hundreds, necessitates the integration of AI-supported systems. These systems can autonomously resolve most operational conflicts, optimise coordination, and significantly enhance the overall efficiency while limiting operational costs. Besides, it should be acknowledged that AI is enhancing, en masse, the quality of decisions made. AI would also make it relatively simpler for unmanned maritime vehicles to conduct the distinction, proportionality assessments, and targeting of military objectives at sea (Kadlec, 2025, p. 497). This will not only deliver the technological advances that NATO seeks (NATO Science and Technology Strategy, 2025, p. 4) but will also strengthen its deterrence posture and its ability to repel potential adversaries.

Conclusions

The southern Baltic Sea is expected to change rapidly in the coming years. In this regard, the volume of maritime transportation will increase as well as the size of the average vessel. In parallel with these phenomena, processes related to the planning and development of maritime areas will accelerate. This will be influenced by the growing demand for electricity in coastal regions as well as the global trend towards energy transformation. The southern Baltic Sea area, which is already heavily designated for specific functions, will within the next dozen or so years become a highly developed basin, with numerous wind farms located on shoals and shallow coastal areas, and rather narrow corridors serving as maritime transport routes. Spatial management itself will certainly be more efficient with the use of AI; importantly, the management of space (above water, on water, and underwater) as well as the traffic within it, taking into account safety concerns, will not be possible without strong support from AI-assisted systems.

Considering that MSP is a highly complex, multi-year process involving the interests of numerous stakeholders—some of which may be compatible while others are mutually exclusive—the integration of AI into this process is likely to be highly beneficial. AI has the potential to make the planning process more efficient and flexible while supporting long-term sustainability. By processing vast amounts of data—including inputs from drone sensors, geospatial and hydrographic data, seabed surveys, satellite or aerial imagery, AIS signals, and historical weather patterns influencing current climate change—AI can provide planners with dynamically updated spatial maps and comprehensive risk assessments, both current and predictive. This would enable a more adaptive and proactive management, allowing planners to respond rapidly to shifts in activity patterns and environmental conditions based on solid, evidence-based insights. Most importantly, AI can enhance the transparency of MSP by visualising complex datasets in formats accessible to all stakeholders. The technology also provides help in other aspects. The development of unmanned vehicles is already bringing a new dimension to the perception of maritime threats and security. This process will deepen, and unmanned and autonomous vehicles will be able to effectively expand the range of tools used in hybrid warfare at sea and increase their effectiveness. AI would also provide support and would be used to increase the frequency of monitoring the seabed, surface, and airspace. Thanks to drones, it will be possible to maintain a constant and effective force ready to repel attacks on critical maritime infrastructure. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that managing multiple drones will not be possible without the implementation of AI systems, which would not only provide support but also take some decisions, similar to what watchkeepers do now while keeping watch in maritime operational centres.

With drones and MSP tools integrated into operations, managing the maritime domain—including the airspace above the water, the surface, and the subsea environment—becomes significantly more effective. These three spatial layers are becoming increasingly saturated and interconnected, creating a complex operational landscape. Human oversight alone is clearly insufficient to continuously monitor, assess, and respond to the dynamic and expanding range of threats emerging across these domains.

Without AI support, ensuring maritime security would not only become increasingly difficult but also more susceptible to human error—errors that could jeopardise navigational safety, environmental protection, and, ultimately, a state’s reputation and the authority of its political leadership. AI is, therefore, not merely an optional enhancement but a foundational requirement for modern maritime governance.