The term ‘hybrid’, used in connotation with military domain, proved to be very popular at the beginning of the current century. It is linked with using other than military tools in combination with military pressure to influence the security situation in other opposing nations. It is based on the valid assumption that it is not necessary to use combat power in a globalised world to impact on the internal situation of other nations, which could lead to their partial or complete subordination. It was closely related to Russian operations in Georgia and later in Ukraine by the utilisation of asymmetric methods to subordinate Crimea without conducting large-scale military operations. Michael Kofman stated that just

“in two short years, the word has mutated from describing how Moscow was fighting its war in Ukraine incorporating all the various elements of Russian influence and national power. The term continues to evolve, spawning iterations like ‘multi-vector hybrid warfare’ in Europe. Hybrid warfare has become the Frankenstein of the field of Russia military analysis; it has taken on a life of its own and there is no obvious way to contain it” (Kofman 2016).

Those two wars in 2008 and 2014 proved that approaches to warfare are evolving when compared to the regime change in Iraq when a large-scale multinational force was used or the supporting of rebels in Libya with NATO’s air power. Therefore, “hybrid threats incorporate a full range of modes of warfare, including conventional capabilities, irregular tactics and formations, terrorist acts that include indiscriminate violence and coercion, and criminal disorder. These multi-modal activities can be conducted by separate units, or even by the same unit, but are generally operationally and tactically directed and coordinated within the main battlespace to achieve synergistic effects in the physical and psychological dimensions of conflict” (Hoffman 2009, p. 36).

The ‘hybrid warfare’ concept supported by new technologies and opportunities has been evolving over the centuries challenging contemporary democracies and threatening them via evolving attacking options. This is a tool exploited by some nations, illegal organisations, terrorist groups etc. as they do not have any moral and legal impediments stopping them. Constant study of interstate conflicts is required to define multidimensional threats allowing the creation of comprehensive capabilities to face them. The military sphere is just one of many fields a country or an organisation must further and purposely develop to preserve independence. European security is currently very complex in both the south and east part of the continent. It has been necessary to confront a non-military influx of displaced persons and migrants coming from regions affected by conflicts that may lead to losing full control over state borders and disorganisation of internal security systems and partial breakdown of the economic system. In the East, there is a threat of military conflict to be preceded by other means. In relation to the growing threat, armed forces have already been deployed in problematic regions in the south and east of Europe to perform a series of tasks in support of civilian law enforcement entities. Securing state borders, protection of the population, ensuring the functioning of public administration, protection of important infrastructure and performance of tasks for extra-military support of armed forces are the priorities of such a non-military crisis. In Eastern Europe, NATO battle groups have been deployed to enhance security, to show decisiveness and to deter any aggression against member states. The aim of the paper is to show the complexity of modern security structure that is facing ‘hybrid’ challenges. It will present the overall concept of ‘hybrid warfare’ as defined by selected nations and organisations and possible ways of opposing the type of non-military pressure that could lead to an armed conflict. The assessment is that there is strong focus on debates related to terminology, definitions and overall discussion but actions are not implemented by prepared nations to face ‘hybrid’ confrontation using all the available instruments of power in an orchestrated way. This is bringing up such basic questions as: How do we understand ‘hybrid warfare’ in a national context? What are the major vulnerabilities of the national security system? and Are national security related entities prepared to face threats in a coordinated and organised way?

‘Hybrid warfare’ as a concept

The comprehensive approach to develop capabilities for ‘hybrid type’ aggression is a time consuming and enduring process, as it requires overall national effort to prepare proper tools for use. This is a complex process for every entity both internally for its own nation/organisation and externally towards taking action against a would-be aggressor. From an aggressor’s side, it is based on complex analyses of a country, alliance or organisation to be targeted to have a clear understanding as to what tools and in what sequences to use them to achieve the desired end state. From an internal national point of view, it requires coordination among all national security related bodies to develop proper tools and methods to use them in concert as “the political, security, economic and social spheres are interdependent: failure in one risks failure in all others” (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development 2006, p. 7). The asymmetric approach to contemporary operations is a reflection of the complex nature of modern societies, which is, among other things, the outcome of the technological revolution and globalisation processes. These require solid analyses of an opponent to recognise capabilities to be used within the engagement space including the civilian dimension, as “hybrid societies are a mixture of the modern and the traditional. Hybrid societies, in turn, have organised hybrid military forces, and it is these forces that will challenge military and diplomatic planners in the future” (Nemeth 2002, p. 3). This is especially true in relation to nations, which are weak militarily but able to face a stronger aggressor using ‘hybrid’ and nonconventional ways to conduct operations.

Proven examples can be given from the Afghan wars, the US forces struggles in Iraq after defeating regular armed forces, operations in Somalia, initial wars in Chechenia and longstanding conflicts on all continents. During those wars, the western model of armed conflict was developed against a different type of enemy and not based on proper assessment of opponents and the environment and caused casualties and engagement in long-term and costly struggles. The “operationally, hybrid military forces are superior to western forces within their limited operational spectrum. Their main strength lies in the hybrid’s ability to employ modern technology against its enemies as well as its ability to operate outside the conventions governing war, which continually restrain its modern foe” (Nemeth 2002, pp. 68-69, 70). At the same time, the complexity of modern societies requires “the employment of all the means at a nation’s command, short of war, to achieve its national objectives, (…) from such overt actions as political alliances, economic measures, and ‘white’ propaganda to such covert operations as support of ‘friendly’ foreign elements, ‘black’ psychological warfare and even encouragement of underground resistance in hostile states” (Kennan 1948) to undermine the roots of their existence leading to their defeat.

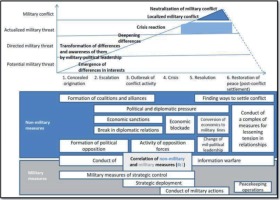

The term ‘hybrid’ started to be more popular after the Russian Chief of General Staff, General Valery Gerasimov, published a paper (Gerasimov 2013; Thomas 2016, pp. 16-19) in which he recognised that a state actor could achieve a desired end state by using a combination of ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ power. The ratio of correlation of non-military and military measures was estimated 4:1 in favour of non-military assets. His approach has also been called the ‘Gerasimov doctrine’. It is noteworthy that Gerasimov was not discussing the term of ‘hybrid warfare’ as the focus was on changes in the reality of ‘nonlinear’ warfare recognising that “the role of nonmilitary ways of achieving political and military goals has been enhanced, which in some cases significantly exceeded the power of armed forces” (Gerasimov 2013). It was visualised by presenting options to utilise both conventional and non-conventional means in a sequence of follow-on phases of an operation (Fig. 1). The author researched conflicts after the Cold War and distinguished that “the role of non-military ways in achieving political and military goals has been enhanced, which in some cases significantly exceeded the power of armed forces” (Gerasimov 2013). Gerasimov at a meeting of the Academy of Military Science, elaborated on the fundamental changes in warfare because of the increased role of non-military resources applied to achieve political and strategic objectives. He emphasised that they have been proven to be more effective than classical military confrontations between large combat forces. Therefore, contact-free (distance) actions could be used to achieve a desired end state where differences between the strategic, operational and tactical levels, between offensive and defensive activities, are becoming blurred2 (Gerasimov 2013). He claims that asymmetrical activities allowing for nullification of an opponent’s advantage in military combat has leapt to prominence. Using special forces and internal opposition or rebels are normal to establish a permanent front within the whole territory of a hostile country (Kuczyński 2009, p. 159). It was based on studies of the Great Patriotic War, conflicts in the Middle East and Afghanistan and the Northern Caucasus.

The role of non-military measures is significantly highlighted throughout all six phases and strategic deployment of military assets is planned during phase 3 – Outbreak of conflict activity leading to military conflict and combat operations. The paper and ‘new generation war’ concept is closely related to perception of threats which are being faced by Russia, as expressed by Gerasimov later in February 2016 when briefing members of the Academy of Military Sciences. He said, “Russia faces a broad range of multi-vector threats, especially linked to the use of soft power: political, diplomatic, economic, informational, cybernetic, psychological and other non-military means” (McDermott 2016). Therefore, “the main result of Russian military science should be practical, leading the way in formulating new ideas and thinking on these issues” (McDermott 2016).

Roger McDermott, assessing Gerasimov’s works, confirms “the non-existence of a Russian hybrid doctrine, or approach to warfare per se. Rather, according to his public remarks, Gerasimov sees the need to respond to the United States and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), which he claims are forming such capabilities” (McDermott 2016). McDermott estimates that the General was very interested in presenting such a concept as he “was keen to establish himself as a reforming general supportive of the new Defence Minister, Sergei Shoigu, who was eager to continue such efforts albeit in modified form. Consequently, he chose to return to the theme of Russian views of future warfare” (McDermott 2016). Gerasimov has been a very knowledgeable commanding and staff officer with combat experience, and his papers and briefings were based on his personal comprehension of military history and modern warfare allowing the formulation of military thought, which was widely quoted and analysed. In the context of the Russian approach and promotion of the term ‘hybrid warfare’, Nicu Popescu from the European Union Institute for Security Studies claims, “the term itself is a Western description of Russian military practice, rather than a conceptual innovation originating in Russia” (Popescu 2015, p. 1). Therefore, “the West is carrying out its own hybrid operation against Russia in the shape of smear campaigns and the imposition of economic and financial sanctions” (Popescu 2015, p. 1). According to Ieva Berzina, “Russia itself has a sense of being the target of aggressive informative activities from the West” (Berzina 2018, p. 162) and she based the assessment on works of Russian authors like Sergey Rastorguyev, Igor Panarin, Sergey Tkachenko and Andrei Fursov. As an outcome of Russian military thought, the ‘hybrid’ approach was practically executed by using “green men” on Crimea during the bloodless annexation. It caused real concerns and disputes in the West as to the boldness and effectiveness of such a way of conducting operations against an independent nation. In parallel, using natural resources to pressure other nations, cyber-attacks against selected military and non-military targets, successful diplomacy to divide opponents underpinned by an armed forces build-up show that ‘hybrid warfare’ is now not just a theory – it is reality. It was a wake-up call asking for a consolidated attitude to avoid such acts against any European Union nation or NATO member. The concept of hybridity in the context of security could be additionally explained as:

“a mixture of different methods – starting from the soft ones, such as informational war, cyberspace war, propaganda, psychological operations, up to the hardest ones, also with military involvement. We deal with the soft ones on an everyday basis, which might be observed Russian action aimed at intimidating the public opinion of other countries” (Koziej 2015).

In modern military conflicts, definitions of hybridity vary as it is defined as a “combination of symmetrical and asymmetrical war” (McCuen 2008, p. 108) drawing a connection between three sources of danger: irregular activities (guerrilla); classic conflicts (but limited in scope) and asymmetrical threats (McCuen 2008, p. 103). It is a logical combination of strategy and tactics of mixing various types of military activities (Lasica 2009, p. 11) or as a synergistic fusion of conventional and non-conventional forces in conjunction with terrorist acts and crimes (Hoffman 2007, p. 14).

According to R. G. Walker, hybridity is a result of a convergence of rules of conventional warfare and special operations (Walker 1998, pp. 4-8). His definition fits the theory of Toffler, pointing out the increase of special operations’ significance in modern conflicts. Walker underlined the so-called demassification of world threats, replaced by multitudes of regional threats, yet exerting influence on a global scale. Special Forces are best equipped to deal with them and could be used “in any type of warfare, from nuclear confrontation to tribal border skirmishes” (Walker 1998, pp. 4-8). Therefore, ‘hybrid warfare’ is a fusion of classic military activities, both the regular and irregular ones (guerrilla warfare, sabotage, diversion, terrorist attacks) in combination with elements of informational warfare (propaganda, disinformation) and cyber warfare, as well as actions conducted in political, economic and cultural spheres. For Walker, the concept of ‘hybrid warfare’ reflects the US perception of modern warfare and constitutes an attempt to answer why the United States failed to use the position of global hegemony and took advantage of engaging with a considerably weaker opponent in the so-called peripheral conflicts both in Iraq and in Afghanistan (Walker 1998, p. 10). As aptly pointed out by Michael Evans “we are facing a strange mixture of pre-modern and post-modern conflict (...), with mosques and Microsoft programmes in the mix” (Evans 2003, p. 137) and military power is not guaranteeing victory. Hybridity may, therefore, be defined by (Wojnowski 2017, p. 8): applying variable methods of conventional war and asymmetrical activities; using mass-scale acts of terror, violence and crimes; surprising an opponent leading to taking over the initiative and gaining an upper hand by exerting psychological influence; utilising numerous diplomatic, informational and radio-electronic activities; cyber-attacks; intelligence operations and economic pressure. Herfried Münkler (2004, pp. 97-128) analysed contemporary conflicts and drew attention to so-called pathologies accompanying modern wars, which are exploited differently by parties to the conflict. These are: uncontrolled migration (a hard to control exodus of people from Africa and the Middle East to Europe – the so-called southern flank), human trafficking and sexual violence (e.g. the situation of Syrian women in refugee camps in Turkey), drug smuggling and trafficking, as well as overexploitation of raw materials and culture (e.g. trade of stolen cultural heritage in Iraq and by Islamic State). This would mean that modern armed forces are required to combine their combat capabilities with those held by law enforcement forces and authorities, such as police, border guards, customs service, etc.

Perception of ‘hybrid’ threat

NATO recognised the complexity of ‘hybrid warfare’ in the report “Multiple Futures Project. Navigating Towards 2030” released by the Allied Command Transformation in 2009. The report explained that security is evolving and it is necessary to “identify potential roles within the military realm that NATO could consider emphasising for 2030”; among them, the first focus area was described as the requirement to enhance readiness to face “the demands of Hybrid Threats” (Multiple Futures Project. Navigating Towards 2030 2009, p. 6). The document saw the implementation of that type of warfare against NATO and its members. It highlighted that there were adversaries who could be

“both interconnected and unpredictable, combining traditional warfare with irregular warfare, terrorism, and organised crime. Psychologically, adversaries will use the instantaneous connectivity of an increasingly effective mass media to reshape or summarily reject the liberal values, ideas, and free markets that characterise the Alliance” (Multiple Futures Project. Navigating Towards 2030 2009, p. 7).

Consequently, an opponent is ready to apply all available tools, using all opportunities, and exploiting all identified weaknesses within the engagement space to influence NATO and its strategic partner, the European Union. It is to be used to weaken nations’ economic and political leadership to undermine cohesion, to influence societies and to shape their perception of threats. That type of warfare is to be exploited by foe organisations, radical elements and terrorist groups, which are not limited by moral and ethical values denying their destructive actions. There was a perception that those types of enemies use hybrid type operations, as they are too small to face any nations or alliance openly. The Ukrainian crisis showed that state actors are also successfully employing such a complex combination of non-military and military methods. The application of ‘hybrid warfare’ methods by a nation makes the situation more complicated as there are many more possible apparatuses, which in some cases could even involve using weapons of mass destruction. In general, “risks and threats to the Alliance’s territories, populations and forces will be hybrid in nature: an interconnected, unpredictable mix of traditional warfare, irregular warfare, terrorism and organised crime” (Multiple Futures Project. Navigating Towards 2030 2009, p. 33). The important requirement is to understand the nature of possible threat and to educate military personnel at all levels as to how to identify and oppose them. This is not an easy task as NATO is involved in the full spectrum of crisis response operations, so the prerequisite is to “develop a culture where leaders and capabilities are well suited for irregular warfare or the hybrid threat, while simultaneously maintaining NATO’s conventional and nuclear competency” (Multiple Futures Project. Navigating Towards 2030 2009, p. 57). Such complexity requires a clear understanding of ‘hybrid’ threats at all levels, especially by political leaders, to allow the full involvement of instruments of power.

The annexation of Crimea and war in Ukraine highlighted the importance of utilisation of non-military and military means in parallel. Their skilful coordination allowed annexation of part of a country without a single shot. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg explained in 2015 that behind “every hybrid strategy, there are conventional forces, increasing the pressure and ready to exploit any opening” (Keynote Speech by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg… 2015). According to his statement, ‘hybrid warfare’ is “the dark reflection of our comprehensive approach” (Keynote Speech by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg… 2015) used to destabilise countries, as happened in Georgia and in Ukraine. Stoltenberg agreed with the general understanding of ‘hybridity’, highlighting that the concept as such was “making it much easier to cross borders and to attack at short notice. As a result, to stay ready to react on time with proper assets, the NATO Secretary General explained:

“We need classical conventional forces. Hybrid is about reduced warning time. It’s about deception. It’s about a mixture of military and non-military means. So, therefore, we have to be able to react quickly and swiftly. And when we are increasing the readiness and the preparedness of our forces, well that is also an answer to the hybrid threat. When we are doing more to increase our capacity when it comes to intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, then it’s also an answer to hybrid threats… so, to increase the capability, the readiness of our conventional forces is also part of the answer to hybrid” (Keynote Speech by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg… 2015).

The statement is very valid and it is linked to e.g. Baltic countries, as by shaping NATO and EU nations mind-set, the Russian Federation is able to inflict their decision-making. Such an approach could affect reaction time to support Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in the case of any aggression, especially a ‘snap’ one. Nonmilitary tools could create a supporting environment facilitating both ‘hybrid’ and conventional attack. As for now, aggression is not expected but should not be fully excluded as relying on the cost-effect calculus of Moscow could be miscalculating methodology. Such threat caused by ‘hybrid’ aggression is recognised in the US “Joint Operating Environment JOE 2035”. In the document, it is evidently stated that “a number of revisionist states will employ a range of coercive activities to advance their national interests through combinations of direct and indirect approaches designed to slow, misdirect, and blunt successful responses by targeted states. These hybrid stratagems will be designed to spread confusion and chaos while simultaneously avoiding attribution and potentially retribution” (Joint Operating Environment JOE 2035 2016, p. 6).

Facing comprehensive aggression

In response to the phenomenon referred to as ‘hybrid warfare‘, a nation must be prepared for non-conventional operations below the threshold of war. This includes propaganda campaigns, informational and psychological activities, and exerting economic and social pressure. This is required, as an opponent could use all the available means to antagonise society; by resorting to legal measures, weakening the trust in legal government and self-government authorities and undermining the credibility of public institutions. The goal of all these activities is to affect the will and response time of leaders and to change society’s attitude towards its own country. Consequently, a society must be aware that ‘hybrid’ conflicts are already a reality and there is a need to find reasonable ways to face them and to make effective and timely decisions. Within that context, to counteract ‘hybrid warfare’, crucial tasks associated with monitoring local developments, reconnaissance, surveillance and patrolling the border area are among the responsibilities of the Territorial Defence Forces (Territorial Defence Forces n.d.). They need to be used to preserve contact with the local population and national minorities within a given territory. Protection of the local population, securing local authorities and ensuring the availability of communication routes are the spheres of extensive cooperation between the Territorial Defence Forces and the Border Guard. When fighting a hybrid threat, it is important to coordinate the tasks of combat forces with territorial defence units, the Border Guard and non-military forces at a time of crisis and war. Professor Michalski recognises a few phases of an attack against a nation as follows:

warfare over minds (cultural and historical warfare, politics);

propaganda and historical tools;

cyberspace warfare;

economic war;

paralysis of state and local centres of power, structures of strength, media and business representatives;

spontaneous establishment of the separatist groups acting with support of the armed forces and special forces of an aggressor;

limiting the possibilities for the armed forces and the ministry of the interior and administration to conduct their activities;

full-scale military operations (Michalski 2017).

All of them are bound by kinetics and non-kinetics. He explains this based on the example of Poland, which has been attacked on numerous fronts for many years, but with variable intensity (Michalski 2017). The historical politics of Russia are far more conservative and long-term oriented and focused on undermining the position of Poland on the international scene, resulting in some western media and politicians to believing Russian propaganda proclamations. In propaganda and psychological warfare, the greater the lie is, the easier people will believe it. It is a harsher type of first stage hybrid warfare, i.e. warfare over minds. The most recent example of immediate activity against Poland is a series of articles and reports on Polish politicians, and an attempt to discredit the Polish initiative to present a different picture of the history of the Second World War and post-war communist period. The follow-on stage includes cyber-attacks, connected with exploitation of the outcome of previous stages, using e.g. the internet, social media, fake news, trolling, i.e. writing negative comments under anti-Russian articles or the entire media apparatus (Life News, Russia Today), which is also very active across social media3. Besides, cyberspace creates an opportunity to strike (paralyse) the critical infrastructure of a state directly. It needs to be emphasised that cyberspace is a binder that joins non-kinetic stages of the hybrid warfare with the kinetic ones.

Subsequently, it is about: paralysing state government and local legal authorities, representatives of media and business through: establishing selected friendly individuals at posts in state and local administration acting for the benefit of an aggressor; infiltrating the armed forces, special services and decision-making circles of the Ministry of National Defence, the Ministry of the Interior and Administration and the strategic companies of the Ministry of Treasury; influencing politicians or entire political parties. The outcome is disruption to the functioning of administrative centres and state treasury companies crucial for defence. Paralysis of state and local administration centres, structures of strength, representatives of media and business is a very long process but it constitutes an introduction to kinetic activities. In Poland, radical nationalistic and radically left-wing parties are the ones most susceptible to Russian influence (their leaders might be invited to meetings in Moscow under variable pretences – e.g. the Hungarian party Jobbik is coddled by the highest Russian authorities). It is also possible to set entire political parties from the ground up, to sponsor them and affect the political landscape in Poland through them. The sport fans communities (along with their leaders) might also be used by the aggressor’s intelligence to fire up social unrest, whether they are aware of this fact or not.

The subsequent phase of ‘hybrid warfare’ is economic warfare such as taking over the companies belonging to the Ministry of Treasury; destabilising the financial system; imposing embargos and protective custom duties; using crime and mafia structures to reduce state budget income and discrediting the country on international exchange markets. An example could be high gas prices for Polish customers and promoting the ‘Nord Stream 2’ concept, which is against Poland’s interest. The final effect might be the intensification of the economic dependency of a state and decreasing its credibility on financial markets. To pursue this, there could be an attempt to limit the capabilities of armed forces and the Ministry of the Interior and Administration by eliminating key personnel in charge and the leadership of the armed forces and selected units, preventing them from entering emergency areas or disrupting their entry, sabotaging and disrupting command and communication systems. It could be followed by a classical military operation or Crimean type variant in relation to Poland and to the Baltic countries. In every case, national armed forces will be first to fight followed by NATO units. In the event of aggression, powerful reaction is important for NATO credibility and unity. The challenge is the asymmetric approach, as Russian activities in the Crimea and in the Eastern Ukraine showed skilful and effective use of the special services and forces, opposition groups (irregular subunits), and militia (Cossacks). It was repeated in the economic sphere (gas blackmail) and the information war. Because of the rather passive reaction in Europe, Russia initiated a separatist movement in the Eastern Ukraine but faced a decisive response from Ukraine. Such a surprising approach to warfare validates the assumptions presented by Thomas Huber. He perceived it as Compound Warfare (Huber 2002, p. 1) a “simultaneous use of regular or main forces and irregular or partisan forces against an opponent” (Huber 2002, p. 1). This means an increase of military influence (combat capabilities) by applying both conventional and non-conventional forces at the same time. In his reflections on the issue, the author states that without synergistic command, with no network-centric management of military operations and with no proper combat area situational awareness, in which the key role should be performed by intelligence services, simultaneous use of regular army units and scattered irregular (special) forces will not be effective in combat activities.

The aspect of hybridity

Examples of the ‘hybrid’ approach include the armed struggle for Islamic identity and values (the fight against globalisation and the western lifestyle; religious conflict between Sunnis and Shiites); ISIS operations (the organised fight against Syrian, Iraqi and coalition forces), unconventional forces (guerrilla and opposition groups operating e.g. in Libya and Mali) supported by terrorist attacks (France, Belgium, etc.) and criminal activities (organised crime). All these activities are reinforced by exerting information warfare aimed at evoking and constantly raising awareness of threat among opponents using all available media. Many receive external support e.g. ISIS is financed by Sunni states (Dozier 2018; ISIS Financing 2015 2016, p. 20). It should be stressed, however, that the complexity of contemporary conflicts and the variety of ways and means of resolving them dictates that a visible difference between the parties does not necessarily mean strategic imbalance between the opponents. Although coalition forces are far more capable than ISIS, the political and cultural complexity of the Middle East means that the Islamic State is still not defeated. It validates the thesis that technological supremacy, organisational excellence and psychological superiority are not the decisive factors for ultimate success today. In that context, the Defence Lexicon definition of asymmetry as “a different way of thinking, organising and acting, resulting from social, civilisational and military factors, pursuing victory by maximising one’s own strengths and exploiting the weaknesses of an enemy” (Huzarski Wołejszo 2014, p. 173) is valid. The forms of asymmetry are disproportion, difference and incompatibility within classical and non-classical asymmetry. The latter is divided into “asymmetry of involvement, civilisational and cultural asymmetry, technological asymmetry and systemic asymmetry” (Huzarski, Wołejszo 2014, p. 173). It is linked with asymmetry of engagement, which includes involvement of not only armed forces but also of society as a whole in the course of military activities. The asymmetry of engagement also applies to the role, duration and extent of participation in a conflict. It is closely related to “the factor of willingness to engage in a fight, but most often it occurs in conflicts entailing a great cultural difference between antagonists. It emerges when one of the opponents is mentally prepared for a long battle, while the other wants to finish it as soon as possible” (Huzarski, Wołejszo 2014, p. 175). Closely associated with this definition is the civilisational and cultural asymmetry, which refers primarily to hostile parties’ perception of war and is considered through the prism of civilisational achievements, such as: the way of exercising power, the socio-political system, education of society, its religion and the standard of living (Huzarski, Wołejszo 2014, p. 173). Globalisation supports the use of ‘hybrid’ type tools, as the access to other countries in all modern society domains is much easier.

Interesting conclusions on hybrid activities were drawn from Israeli actions in Lebanon against Hezbollah in 2006, and Hamas in 2009 (Johnson 2010). David E. Johnson, assumed that in 2006, the methods of fighting local rebels/terrorists used in the conflict in Kosovo (1999), Afghanistan and in Iraq turned out to be ineffective. As Israeli military personnel were focused on training for a Low-Intensity Conflict (LIC) and to counter-terrorism activities, it was not possible to conduct joint operations4 which caused casualties. Similarly, Russia suffered losses in Afghanistan and Chechenia by not being adaptable at short notice to a new type of enemy. This was similarly true for US and coalition forces’ struggles in Afghanistan and Iraq. Experience gained from the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and from the Arab Spring clearly shows that it is essential in modern wars to be able to combine military operations with civilian management, not only in crisis and post-conflict situations, but also in the course of a conflict. During the flow of military intervention, an asymmetric advantage of the armed forces of a state or a coalition is sufficient to take control over a given area and to create conditions for establishing local institutions of state authority. The hypothetical scenario of a hybrid conflict could be part of the routine activity of Military Intelligence and Special Forces allowing increased tensions in bilateral relations. It could lead to initiation of an information war, including the use of disinformation and propaganda elements using media platforms, such as “Russia Today”, “Sputnik” radio, as well as social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram) and activities in cyberspace (cyber espionage, attacks on selected portals related to national security).

The next phase is about further actions of the Military Intelligence and the Special Forces; accelerating military build-up; violation of airspace and territorial waters; cyberattacks on communication systems, defence and security subsystems, state economy and finances, the power sector, transport, and the health service and intensification of cyber espionage, using captured resources, as well as through sponsored groups. In addition, an attempt to divide society using ethnic and national minorities to organise demonstrations, riots, unrest, and to trigger events, “accidental disasters” by controlling critical infrastructure, such as bridges, power plants, pipelines, road junctions, etc. The follow-ons are attempts to create conditions for:

utilizing operational and special activities to influence the economy/finance of a state by using the acquired companies/companies of strategic importance,

violating the state border in order to check reactions and run a reconnaissance of border protection system,

creating trafficking channels and “leakage” of the state border and provocations, intimidation of local government officials, the border guard, and the police.

In addition, attacks on critical infrastructure, “blackouts”, sending advisors (“instructors”) to criminal groups and supporters, recruitment and training paramilitary groups, provoking riots and public demonstrations especially in areas where national minorities exist are present. The final stage is the direct threat of combat and special activities including crossing borders and creating logistics bases, kidnappings, murders, assaults, roadblocks, hampering communication facilities, elimination of individual targets, mass attacks in cyberspace, reconnaissance and disorganisation of the defence system. It is assumed that command and communication systems of military units and state administration will be disrupted, military traffic will be blocked, the mobilisation process will be disturbed, local administration facilities and entire towns will be seized, riots will be provoked, and Western countries will be deterred by demonstration of military power and the political will to use it.

Conclusions

In conclusion, it is worth noting that ‘hybrid warfare’ is a fusion of classical military activities, both the regular and the irregular ones (guerrilla, sabotage, diversion, terrorist acts), combined with elements of informational warfare (propaganda, disinformation) and cyber-warfare, as well as activities carried out in the political, economic and cultural spheres. It is a non-declared war, and according to international law, formally it is not even a war. Taking into account the conclusions of the ‘hybrid warfare’ analysis, it is possible to consider the occupation of the Crimea by Russia as a model example of conducting hybrid activities through a skilful combination of informational warfare, exercising political and economic influence, supported by activities of special services, armed forces and irregular sub-units. An attempt to reiterate this type operation in eastern Ukraine failed which highlights the complexity of the modern security environment and confirms the rule stating that every war is different. It must be recognised by civilian and military leaders that combat power, technological superiority, organisational brilliance and psychological advantage alone are not the decisive factors guaranteeing victory in a conflict today. Modern armies should make use of more flexible methods of fighting and the means to engage with both classic and new opponents with a different degree of organisation than a regular army (Al-Qaida, Hezbollah). The essence of this new opponent’s activity is the wide use of unconventional methods, often going beyond the standards of international law (e.g. attacks on civilians), and avoiding the places and areas where opposing forces have a definite advantage. All the above factors must be understood by civilian and military decision makers causing them to work closely together. This is linked with using proper tools and capabilities during different stages of recognised ‘hybrid warfare’ against one’s own nation following the logic presented above that the ratio between non-military and military actions is in favour of the former.