Introduction

The aim of this research is to identify cutting-edge studies on leadership applied to police work, especially in critical or dangerous contexts. An integrative literature review was carried out to collect and analyse relevant scientific articles indexed in the selected databases, in addition to bibliometric analyses using VOSviewer software and trends by subject analysed using the Google Trends tool.

Every country has a police institution. The emergence of the police does not fit into a well-defined period, since maintaining order in a clan, village, or city goes hand in hand with the development of civilisation. In contemporary democratic societies, the police are the embodiment of public power and are considered the main arm of the state in matters related to public order and establishing a climate of harmonious, peaceful coexistence for the public good (Hipólito and Tasca, 2012).

As societies become more heterogeneous and complex, the role of the police is increasingly demanding and multifaceted, and typical functions and tasks can quickly change depending on contextual factors. Police officers must develop specific skills and possess personal qualities to carry out their role. A study of police officers from six European countries found three important characteristics of police work: leadership, knowledge, and the ability to establish good relations with citizens (Inzunza and Wikström, 2020).

Police work, in itself, is a dangerous job. Dealing with crime on a daily basis, either preventing or repressing it, places the work of these individuals among the most dangerous professions in the world. “Physical injuries are only some of the risks faced by police officers; another important dimension of the hazards of police work is the psychological consequences” (Brandl and Stroshine, 2012, p. 14). In the United States, police work is among the 25 riskiest professions, with high rates of fatal accidents or injuries resulting from the activity. Working as a police officer in the US is about four times more dangerous than the average job (considering the workplace fatality rate). In 2018, 108 deaths of police officers were recorded (University of Delaware, 2020). In Brazil, the rates are even higher, more than triple for the same year, with 343 police officers killed on duty (Brazilian Public Safety Forum, 2021).

This study’s context of interest is made up of cases considered critical, high risk, dangerous, and defined “as those in which leaders or their followers are personally faced with highly dynamic and unpredictable situations and where the outcomes of leadership may result in severe physical or psychological injury (or death) to unit members” (Campbell et al., 2010, p. 3).

Understanding how leadership manifests itself in critical contexts is essential for people’s integrity and management of the process. “In crisis situations, leaders must often manage resources at a location they did not choose, quickly diagnose problems on less than complete information, and make critical decisions that may send subordinates in harm’s way” (Johns and Jarvis, 2016, p. 3).

Leadership is a theme that has been explored by international literature since the beginning of the twentieth century. It is a comprehensive issue, and studies on leadership address many other topics, such as leader characteristics, leader-led relations, and the interference of the context in these behaviours. Leadership has also been the target of specific reviews related to organisational behaviour (Fonseca et al., 2015).

Defining leadership is not simple, as there is a polysemy of the word’s meanings. Northouse (2016), citing a research review by Stogdill (1974) and apud Northouse (2016), points out that leadership has as many different definitions as the number of people who have tried to define it. It would be enough to start a sentence “Leadership is...” and many ways to finish this sentence would be presented. Like democracy, love, and peace, leadership is a word we intuitively know the meaning of, but it can have different meanings for different people. Rost (1991, apud Northouse 2016) analysed written materials from 1900 to 1990, finding more than 200 different definitions for leadership. This shows that scholars and practitioners have been trying to define leadership for over a century without consensus.

Northouse (2016) analysed the many definitions and noticed four central components of leadership: (1) leadership is a process; (2) leadership involves influence; (3) leadership occurs in groups; (4) leadership involves common goals. Based on these components, the author defines leadership as the process by which an individual (leader) influences a group of individuals (followers) to achieve a common goal.

It is necessary to highlight the context in which leadership takes place in any analysed group (Northouse, 2016). This study focuses on the police, and the context is critical events. Despite a plethora of literature and practical guidelines concerning the promotion of leadership in various organisations, for example, military, business, finance, or medicine, “not many published research reports and analyses exist pertaining to police leadership during critical incidents” (Johns and Jarvis, 2016, p. 3).

Given the importance of police leadership in critical contexts for the population’s well-being and social security and the improvement of management tools within organisations – particularly military organisations – this article offers an integrative literature review connecting different perspectives and inspiring new ones.

Methodological procedure of the integrative review

The literature review is the basis for identifying current scientific knowledge and cutting-edge research on a given topic. It is a step in which the researcher needs to locate and analyse scientific publications on the researched topic. “Based on it, it is possible to identify gaps to be explored, and also having a better comprehension of the study object/theme” (Ferenhof and Fernandes, 2016, p. 550).

The integrative review adopted in this study is a method to orderly and comprehensively gather research results on a delimited theme or issue. It contributes to deepening knowledge of the subject investigated (Ercole et al., 2014), enabling “the synthesis and analysis of scientific knowledge already produced on the investigated topic” (Botelho et al., 2011, p. 129, our translation). It is called integrative because it provides broad information about a subject/problem, thus constituting a body of knowledge, allowing the researcher to review concepts, theories, or methodologies of a particular topic (Ercole et al., 2014).

The method includes experimental and non-experimental studies and combines theoretical and empirical literature to understand the phenomenon. Such studies are joined in the review to (1) subsidise the definition of concepts; (2) review theories and evidence on the subject; and (3) analyse methodological problems of a particular topic (Souza et al., 2010).

The integrative review process proposes the establishment of well-defined criteria. It has phases that involve defining the guiding question, literature search, data collection, analysis, discussion, and presentation of results (Lanzoni and Meirelles, 2011; Souza et al., 2010). Table 1 presents a synthetic and visual representation of the integrative review conducted in this study, identifying the phases.

Table 1

Phases of the integrative review.

The integrative review’s guiding question was grounded on an analysis of how leadership occurs during high-risk, critical, unconventional, and life-threatening events related to police and public security activities. The question was: how does leadership manifest itself in police organisations in critical, dangerous, high-risk contexts?

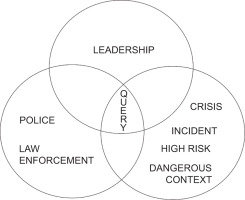

The literature search was conducted considering the search query: (Leadership AND (“law enforcement” OR police) AND (crisis OR incident OR “high risk” OR “dangerous context”)). In this kind of search, the appropriate keywords are selected and combined with logical and relational operators and special characters, standardising searches in the selected databases.

Leadership is the base keyword of the research, and we attempted to combine it with studies applied to police organisations (“law enforcement” or police) and occurrences of crisis, incident, “high risk,” or “dangerous context.”

The Scopus, Web of Science, Ebsco Host, ScienceDirect – Elsevier (focusing on the journal The Leadership Quarterly), Core; and SciELO databases were explored between May and June 2022, using the search query mentioned above by article title, abstract, or keywords, in English or Portuguese, with no limit to the year of publication and areas of knowledge. As for exclusion criteria, articles were excluded if the analysis of the titles and abstracts did not clearly identify that the studies addressed the phenomenon of leadership in dangerous, high-risk, crisis, or incident-related contexts concerning law enforcement or police. Notably, only studies in the format of a scientific article were selected, discarding grey literature1 (such as books, book chapters, theses, dissertations, and government reports).

Scopus was the first database consulted, considering its status as a recognised international database with multidisciplinary content. The search offered 146 results, of which 139 were excluded and seven were selected. In Web Of Science, a database with a wide variety of scientific content, of the 97 articles found, 96 were excluded (of which 1 was a duplicated article already obtained from Scopus), and only one was included. Ebsco Host, an international online research platform specifically for the administration area, presented 115 results, with 113 excluded (three duplicated articles already obtained from Scopus) and two selected. The publications available in the journal, The Leadership Quarterly, were also researched. The journal is accessible through ScienceDirect – Elsevier database and is ranked as Qualis A1 in the Brazilian agency Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) classification – Qualis A1 is the highest rank. The Leadership Quarterly is dedicated to promoting the understanding of leadership in several research fields. The search resulted in 59 articles, of which 57 were excluded and two were selected. CORE, a provider of open-access scientific and academic content data, offered 142 results, all of which were excluded because they did not fit the requirements of the search strategy. The SciELO database was chosen to analyse the publications from Latin America and the Caribbean countries. It presented 15 results, of which three publications were included and 12 excluded. Table 2 shows the summary of the search and data collection.

Table 2

Search strategy and results of data collection.

Table 3

Synthesis of the integrative review.

Therefore, the research corpus resulted in 15 documents for the literature review out of the 574 available in the databases. Most articles were excluded (558) because they did not fit the exact search strategy. In these cases, the studies addressed the descriptors leadership, law enforcement, police, crisis, incident, high risk, and dangerous contexts in isolation or combined, but in a way that did not fit the proposed query. It is inferred that the high number of keywords and Boolean logical operators’ entries led the databases’ selection algorithms to identify broader responses to the described strategy. It is also worth clarifying that the documents from the Core database were excluded because the results that could fit the search strategy were grey literature and not scientific articles. The below table contains a summary of the applied integrative review.

A careful examination was conducted to refine the scientific articles suitable for the search strategy, since the pure and simple launch of the query in the databases did not match the interests of the integrative review. The following section analyses the 15 publications that fulfilled the logical items defined in the search strategy.

Analysis of the results with the query proposed in the integrative review

Table 4 lists the 15 articles that fit our issues of interest – leadership, police, and dangerous context. They are ordered by year of publication, and the table also shows their titles, authors, and databases of origin.

Table 4

Articles that addressed the three issues requested in the search query.

| Title | Authors/Year | Databases | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The importance of context: Qualitative research and the study of leadership | (Bryman et al., 1996) | The Leadership Quarterly (Sciencedirect) |

| 2 | When failure isn’t an option | (Hillmann et al., 2005) | Web of Science |

| 3 | Crisis Negotiation Leadership: Making Ethical Decisions | (Magers, 2008) | Scopus Ebsco Host |

| 4 | A framework for examining leadership in extreme contexts | (Hannah et al., 2009) | The Leadership Quarterly (Sciencedirect) |

| 5 | Leadership in complex, stressful rescue operations: A quantitative test of a qualitatively developed model | (Sjoberg et al., 2011) | Scopus Web of Science |

| 6 | Informal Coordination Elements in a Police Special Operations Unit | (Zanini et al., 2013) | Scielo |

| 7 | An empirical examination of special operations team leaders’ and members’ leadership characteristics | (Arnatt and Beyerlein, 2014) | Scopus Ebsco Host |

| 8 | The influence of the consultative leadership style in the relationships of trust and commitment in the Special Police Operations Battalion of Rio de Janeiro’ | (Zanini et al., 2015) | Scielo |

| 9 | Conflict and compatibility: Perspectives of police officers with and without military service on the military model of policing | (Shernock, 2016) | Scopus Ebsco Host |

| 10 | Leadership During Crisis Response: Challenges and Evolving Research | (Johns and Jarvis, 2016) | Ebsco Host |

| 11 | A preliminary analysis of high-stakes decision-making for crisis leadership | (Oroszi, 2016) | Scopus |

| 12 | An analysis of the antecedents of trust in the leader of a special operations police unit | (Zanini et al., 2018) | Scielo |

| 13 | Leadership During Crisis Response | (Jarvis and Murray, 2019) | Ebsco |

| 14 | How contextual is destructive leadership? A comparison of how destructive leadership is perceived in usual circumstances versus crisis | (Brandebo, 2020) | Scopus |

| 15 | Asymmetries of leadership: Agency, response and reason | (Tomkins et al., 2020) | Scopus |

After reading each of the 15 publications, we sought to identify the main types of leadership, findings, and methodologies addressed to diagnose the scientific production of the highlighted topic.

Bryman et al. (1996) investigate leadership in a sample of 146 police officers in England, focusing on analysing traditional leadership, new leadership, and nonleadership (laissez-faire). Through semi-structured interviews, they found that instrumental leadership was much more widespread in the thinking of police officers as central to effective leadership and that charisma was not as prominent in the notions of what makes an effective leader according to the postulates of the new leadership. The reasons for such findings are attributed to contextual sensitivity, which is why researchers highlight the importance of qualitative research for studies involving leadership. Instead of following universal prescriptions, the qualitative approach values the context and allows the construction of evidence in different spheres.

In a theoretical essay that analyses leadership in negotiation contexts in crises in America, Magers (2008) highlights the importance of ethical leadership, since moral dilemmas appear for decision-making in situations involving hostages or barricaded criminals. Decisions to execute a tactical plan rest with the crisis manager, who, as a rule, follows action criteria with three questions as part of the decision-making process: (1) Is the action necessary? (2) Is the action risk-effective? (3) Is the action acceptable? Thus, effective crisis leaders not only rely on knowledge and technical skills, but also examine and prepare for various ethical challenges.

Hannah et al. (2009) propose a framework for examining leadership in extreme contexts. For the authors, extreme contexts are different from crises. Crises comprise the threat to a high-priority objective and demand reactive responses with little response time. On the other hand, extreme contexts reach the threshold of “intolerable magnitude,” which may exceed the organisation’s capacity to prevent these events from happening. The framework is founded on five components: magnitude of consequences, the form of threat, probability of consequences, location in time, and physical or psychological–social proximity.

An article written by a leader of high-performance teams in the Special Operation Bureau of the Los Angeles Police Department, leaders working in organisations such as the World Bank and the National Fire Academy, a career coach for players of the Cleveland Browns, a planner of society weddings, galas, and other events, and a leader of a Stock Car racing team (Hillmann et al., 2005), concluded that, despite the professional differences, some similarities emerge in how teams consistently perform at the highest levels. For example, selecting team members is crucial, as is the willingness to weed out members who do not consistently perform. It is essential to count on a leader who supports and builds trust – teams without such a leader often identify one informally. Finally, the stress that defines these teams’ work helps generate short-term peak performance and poses the constant risk of member burnout.

Sjoberg et al. (2011) studied leaders of the ambulance and rescue services and the police force in Sweden, concluding that the most important factors to explain the outcome of complex operations were the organisational climate before the incident, positive reactions to the stress, and technical knowledge of the co-actors during the event.. The research adopted a quantitative approach tested on 385 participants from three organisations with leadership experiences during complex or stressful rescue operations. Among the limitations of the research were the high dropout rate and the fact that there were comparatively few large-scale rescue operations.

Three studies were carried out with a special operations police unit (BOPE) of the state military police of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Zanini et al. (2013), Zanini et al. (2015), and Zanini et al. (2018). The approaches were quali-quantitative, with in-depth interviews and the sending of questionnaires to 400 police officers, with a sample of 128 police officers in the first study and 115 in the last one. Zanini et al. (2013) point out that the sense of common mission, the quality of leadership, and the quality of the bonds between the members of the organisation (based on loyalty and high trust) and between the members and the institution, are the explanatory factors of the quality of the organisation’s informal coordination in the teams of the special operations unit researched. When analysing the consultative leadership style, Zanini et al. (2015) found that leadership and trust partially explain the quality of informal coordination in the unit’s teams. These same factors explain the propensity for extreme risk for operations and focus on results. Zanini et al. (2018), when deepening the understanding of the elements of informal coordination in the management of teams that operate in complex and unpredictable scenarios, found a direct and negative relationship between power distance and professional trust in the leader, and a direct and positive relationship with some antecedents of trust. The greater the perception of the quality of internal communication and the sharing and delegation of authority in decision-making processes, the greater the trust in the leader.

In a study to examine the characteristics of leaders and members of law enforcement special operations teams (e.g., SWAT, Swift, HRT, and Strategic Response Teams), Arnatt and Beyerlein (2014) conducted a quantitative survey by giving the Authentic Leadership Questionnaire (ALQ) to 99 members of the US local, state, and federal special operations team. The findings reveal that members and leaders differ regarding scale scores that represent relational transparency, morals and ethics, sociability, and disaster self-efficacy. The authors warn that despite the importance of police special operations teams, there is virtually no empirical research specifically addressing leadership within these teams.

Another study in the United States compared the perspectives and compatibility of police officers with military experience in combat and others without a background in military service (Shernock, 2016). The author observed that a military background had positive consequences both for the police service and for the service provided to the community. The study also showed that military leadership increases the ability to face stressful situations. The study’s approach was quantitative, and data was obtained through an online survey of police officers in a rural Northern New England state. A total of 266 officers participated out of a population of 1,150.

For Johns and Jarvis (2016), there is limited knowledge of leadership in crises, and many people think that the simple application of leadership protocols – which may be sufficient on a daily basis – will be equally effective during critical events. This seems to be reductionist reasoning in the face of the statement, “the nature and scope of leadership required to effectively respond to crises may, in fact, be different in the confusion of these situations” (Johns and Jarvis, 2016, p. 8). In another study, Jarvis and Murray (2019) find that leadership exercised during a crisis represents a conglomerate of personality, experience, motivation, support from others, and trust. Ongoing practice is necessary because skills need regular exercise, evaluation, and adjustment to get the best chances for an optimal result.

Oroszi (2016) discusses high-risk decision-making as a critical component of crisis leadership. The study examined the decision-making processes of professionals in leadership positions in the national security, law enforcement, and government sectors, identifying that crises have different factors: they are time sensitive, pose substantial risks, and demand consequential decisions. The qualitative approach was conducted with 15 professional experts in crises.

Brandebo (2020) explores the differences between destructive leadership in two different contexts: crisis management and everyday circumstances. The study emphasises the importance of leaders’ task- and strategy-oriented behaviour and building trusting relationships with subordinates. The results highlight the importance of leaders creating and maintaining good relationships with their subordinates in everyday conditions. The quantitative research was carried out in Sweden, and the questionnaire was applied to 337 individuals with experience handling various societal crises, such as terror attacks and forest fires. The respondents represented four different organisations: municipalities, county administrative boards, the police, and the emergency services.

Tomkins et al. (2020) end the list of 15 articles selected in this research with a study conducted in a British police organisation. They analysed leadership asymmetries, noting that leaders expect and have responsibility for much more than they can control, experience more blame than praise, and interpret the reasons for failure based more on personal fault than on situational or task complexity. For the authors, leadership in police activity involves a combination of the necessary and the impossible, in addition to resilience in the face of the paradoxical perspective of being held accountable for success as readily as for failure. The reflections of the study are derived from an action research project in a major city police service in the UK. Over two years, researchers collected data through in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 57 volunteers who were leaders, officers, and staff in administrative and frontline policing functions.

In conclusion, it should be noted that all databases searched, articles from only three policing journals were found: “Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management” (Arnatt and Beyerlein, 2014) and (Shernock, 2016); “FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin” (Johns and Jarvis, 2016) and (Jarvis and Murray, 2019); Journal of Police Crisis Negotiations (Magers, 2008).

Bibliometric analysis using VOSviewer software

VOSviewer was developed by Van Eck and Waltman (2021) from Lenden University. This software was designed to build and visualise bibliometric networks, allowing one to assess citation relationships, bibliographic coupling, co-citation, or co-authorship based on a specific research focus.

Bibliometrics is a statistical method that can quantitatively analyse research papers on a particular topic through mathematical methods. It also gives access to the quality of studies, examining key areas of research, and predicting the direction of future studies (Yu et al., 2020).

Bibliometric analysis of citation, co-authorship, and occurrence of keywords makes it possible to assess the evolution of a field of knowledge. Citation analysis helps identify influential articles within a given body of literature (Linnenluecke et al., 2020). Co-authorship analysis examines the social networks that scientists create when collaborating on research, allowing verification of co-productions, social networks, authors’ affiliations and their geographic location, and cooperation at the level of institutions and countries. Keyword occurrence analysis is a technique that uses words in documents to establish relationships and build a conceptual structure of the domain. The idea behind the method is that when words frequently co-occur in documents, the concepts behind those words are closely related. This semantic map helps with the understanding of a field’s cognitive structure and conceptual space (Zupic and Cater, 2015).

Based on the review that resulted in a corpus of 15 documents, an RIS (Research Information Systems) file was extracted from the Zotero software, a tool that collects and organises bibliographic references. The file was imported into VOSviewer for analysis and showed no bibliometric relationships due to a lack of metadata. We therefore decided to expand the corpus and collect enough data to run through VOSviewer. The strategy was to re-analyse the 574 articles retrieved from the databases and select those that studied leadership in police organisations or leadership in dangerous, critical, high-risk, or incident contexts encompassing firefighters and the armed forces. The rationale was that dangerous contexts, where there is a risk of death for the people involved, usually include military personnel, police officers, and firefighters with a history of combat (Campbell et al., 2010; Kolditz, 2006, 2007). 48 articles were thus added to the 15 studies selected in the initial query to form the corpus used in the bibliometric analysis through VOSviewer. Table 5 illustrates the strategy used to form the corpus of 63 articles.

Table 5

Strategy to form the corpus to conduct the bibliometric analysis.

The new research corpus with 63 articles was reorganised in Zotero, resulting in a new RIS file extracted and inserted in the VOSviewer. The software produced two types of analysis: co-authorship and the co-occurrence of keywords , offering a visual representation of maps that connected relevant authors and keywords.

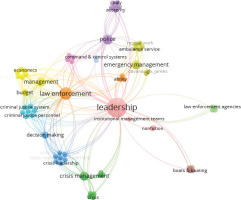

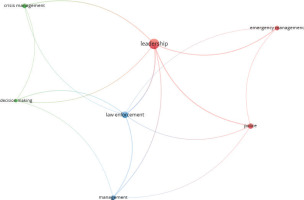

Based on the co-authorship criterion with authors as the unit of analysis, provided that an author has had at least one work published, the tool calculates the total strength of co-authorship, selecting the strongest links. The result is that most of the 129 authors analysed have no connection with one another. Only one cluster with the authors Evernham, Allen, Dongier, Hillmann, Khosh, and Murgallis was formed, evidencing the article extracted from the Web Of Science database, “When failure isn’t an option” published in the Harvard Business Review of 2005. On the co-authorship analysis, considering the option of selecting authors with at least two publications, VOSviewer highlighted six authors: Alan Bryman from the UK, Marco Tulio Zanini and Carmen Pires Migueles from Brazil, T. Casey LaFrance, Sean T. Hannah and Bruce J. Avolio from the US. As for the co-occurrence analysis of the keywords of the literature review, of the 108 detected by the software, 68 were part of the largest connection set, forming a network with leadership as the central word in various clusters (Figure 2).

The node size indicates the frequency of a given keyword, and the curves between the nodes represent their co-occurrence in the same publication. The smaller the distance between two nodes, the more the two keywords co-occur (Yu et al., 2020). In this analysis, ‘leadership’ appears the most and has a strong connection with law enforcement (total strength of link 46), management (total strength of link 27), police (total strength of link 25), decision-making (total strength of link 21), crisis management (total strength of link 19), and emergency management (total strength of link 15). The refinement of the type of analysis for keywords with at least two appearances filtered the selection to 9 words, two of which were excluded by VOSviewer because they are not connected to this network, leaving evidence of the previously mentioned strong ties, as shown in Figure 3.

The exploration of this technological engendering suggests that the concepts of leadership, law enforcement, police, management, crisis management, emergency management, and decision-making are strongly related, considering the extract found in this literature review. It means that from this research focus, the analysis of leadership in law enforcement is closely related to the concepts of management, crisis management, emergency management, and decision-making, which together presuppose the cognitive structure of this field of study.

Trend analysis of police leadership searches using Google Trends

Google Trends is a tool that allows the evolution of the number of searches for a given keyword or topic to be tracked over time in various languages and regions of the world (Farias, 2020). Google Trends looks at a percentage of web queries to determine how many searches were made in a given time. The data is anonymous, categorised, and clustered, which allows the interest in a given topic to be assessed. The tool’s data analysis limit is from 2004 to 72 hours before the search (Google Trends, 2023b).

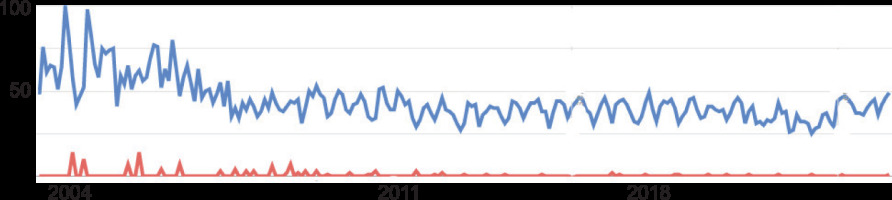

Considering the subject heading leadership, applying the search criteria in the category science, worldwide, and the period from 2004 to the present day, the interest in the subject reached its highest point on the graph in 2004. The term’s popularity fell to 50% by 2007, remaining variably at this level up to today. Using the same criteria but with the descriptor leadership and police,2 the results show some peaks of interest up to 2010. After that, the indexes start to be close to zero. In this case, the only country highlighted by Google Trends with interest in scientific searches on the web about police leadership was the United States. When the search is refined further with the entry of the descriptor leadership and police and crisis,3 the tool informs us that there is insufficient data to display results. Figure 4 illustrates a comparative graph between searches.

Figure 4

Interest over time in the descriptor leadership (blue line) compared to the descriptors leadership and police (red line) (Google Trends, 2023a).

Google Trends indicates that research interest in the subject of leadership on the web, specifically in the science category and worldwide, had the highest increase in the first decade of the 21st century, remaining stable in the 2010s. However, with regard to leadership and police research interests, the results are close to zero, with few peaks occurring in the first ten years. Considering the historical analysis and trends presented by the tool, in which “a line trending downward means that a search term’s relative popularity is decreasing” (Google Trends, 2023b, p. 3), there are indications that the scientific interest in internet searches with a focus on police leadership have a downward line.

In congruence with such findings, the literature from the 2000s onwards shows an “explosion of leadership theories and novelty of approaches to studying leadership” (Gardner et al., 2010, p. 951), which has continued to rise over the last 30 years (Day et al., 2021; Gardner et al., 2020). On the other hand, the same is not seen with the analysis of leadership in police organisations, especially when critical, dangerous, or high-risk contexts are added to the subject.

Discussion and conclusion

Leadership has been studied for over a hundred years. It represents a broad concept and has countless definitions and multiple applications in different areas of knowledge. The theme became popular after the 1980s, entering the twenty-first century with emerging approaches (Northouse, 2016).

The analysis of Google Trends clearly shows this “fashion” of research on leadership. The record peaks of the term leadership in the science category worldwide and from the 2000s onwards demonstrate the apex of interest in the subject. Afterwards, the popularity of the term drops but remains relatively stable. However, when we refine the searches for police leadership, interest in the topic is close to zero. Some peaks coincide with the wave of the early 2000s (the US stood out as the only country interested in the topic according to Google Trends). The tool showed no results when we added context to the searches.

As the internet is notoriously the main means of searching for scientific studies, the results of Google Trends, with data in the billions categorised and clustered, seem to reinforce the findings of the integrative review. The results of the databases were consulted with Scopus, Web of Science, Ebsco Host, ScienceDirect – Elsevier, Core, and SciELO, which are interfaces that process and interconnect thousands of pieces of data, showed only a few articles (indicating reliable and quality publications) that explored the phenomenon of leadership in police organisations and even fewer when adding the interest for such leadership in critical contexts.

The integrative review sought to identify cutting-edge research on leadership in police work applied to a critical context. In an accurate analysis of the research strategy – query – only 15 articles fully met the proposed criterion out of 574 retrieved from the databases. The examination of these publications showed the adoption of various leadership concepts, such as instrumental, transformational, charismatic, consultative, ethical, authentic, military, destructive, and lack of leadership (laissez-faire), with qualitative and/or quantitative approaches. The lack of studies and the multiple approaches, even for the same theme, indicate the need for further research in the area.

For the bibliometric analysis using VOSviewer, the research corpus was expanded from 15 to 63 articles (out of the 574 articles initially retrieved). This measure was taken since the metadata from the 15 articles was insufficient to carry out a bibliometric analysis using the software. The 63 articles were gathered after re-analysing the articles obtained from the databases and accepting studies about the phenomenon of leadership in police organisations or in dangerous, critical, high-risk, or incident contexts that included firefighters and military personnel. The analysis showed almost no co-authorship link between the 129 authors of the 63 articles, meaning that the cooperation network of authors and institutions is very low for this specific topic. The keywords co-occurrence analysis suggests that leadership has a strong link with law enforcement, police, management, crisis management, emergency management, and decision-making, establishing a close relationship between these concepts and a fundamental semantic map of this field of study.

Among the study’s limitations is the selection of databases – assuming that adding other databases would result in a more extensive metadata set that would improve the review. However, the low incidence of studies examining leadership in police organisations in critical, high-risk, or dangerous contexts reveals a clear gap in the literature. It also reinforces the fact that there is room to explore the theme, which is of great value when observing its impact on people’s lives. Good leadership in police organisations in dangerous contexts is decisive for the physical and moral integrity of all those involved – police, victims, third parties, and criminals – as well as for public order and the reputation of the police organisation.