Introduction

The current strategic context resulting from current budget constraints and rapid technological change poses new challenges for states. These challenges require a rapid response capacity from public and private organisations. These organisations should be able to decide, in a timely manner, to respond to the needs of the market, society and the current security environment (Borges, 2013; Garcia, 2015; Gomes, Mendes and Carvalho, 2010; Vicente, 2011). In the context of public organisations, new theoretical movements have emerged within the scope of a New Public Administration: New Public Management (NPM), New Public Governance (NPG), Public Value Management (PVM) and New Public Service (NPS).

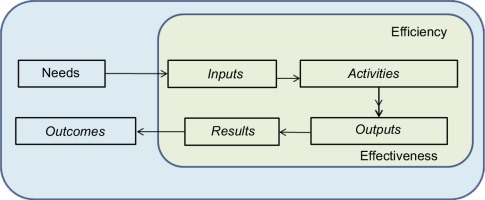

In the New Public Administration, public organisations should produce a public service with higher quality, optimising their performance in terms of the components of the public management cycle (inputs, outputs, activities and outcomes) and the respective efficiency and effectiveness indexes (Alford and O’Flynn, 2009; Gomes, Mendes and Carvalho, 2010; Moore, 2012; O’Flynn, 2007).

The improvement of performance in the public sector is becoming more focussed on the organisational products produced (outputs) and not so much on the resources that come in (inputs), and the results that have an impact on society (outcomes) are also increasingly relevant (Epstein and Buhovac, 2009; Dooren, Bouckaert and Halligan, 2015; Webber, 2004). This approach varies from organisation to organisation, as does the best way to adopt and implement this management process (Dooren, 2005).

One of the current public organisations at the service of the State with the potential to influence the environment, both internally and externally, is its Armed Forces, and it is crucial that they are also at the service of civil society. At the level of Armed Forces, their military capabilities are essential. These are what allow countries to defend themselves against threats and adversaries, national and foreign, in a perspective of being ready to act whenever necessary. These capabilities constitute the output of military power (Aberdeen, Thiébaux and Zhang, 2004; Heng, 2012).

Regarding the performance of Portuguese Armed Forces, under the current Strategic Concept of National Defence, it is essential to develop military capabilities, to face and respond to these threats and risks and to fulfil international commitments. In order for the Portuguese Armed Forces to provide a quality public service with an adequate organisational performance, they should be able to enhance the components of the public management cycle, namely, their final product (output) to allow them to carry out their missions in different scenarios (outcome).

This article aims to analyse the influence that military capabilities have in combatting current threats and risks, in fulfilling the various missions, as well optimising the performance of the Portuguese Armed Forces. In this sense, it is intended to answer the following research question: What is the impact of the military capabilities in the performance of the Portuguese Armed Forces? In terms of methodology, given the nature of this investigation, a quantitative analysis was carried out through data collection from a convenience sample of citizens and Portuguese military officers participating in promotional and training courses at the Portuguese Military University Institute.

Threats to humanity in the 21st century

The current security environment is faced with a wide variety of threats, risks and challenges. The threats and risks may be the same as in the last century but they currently have different acuity and perceptions. In addition, citizens “own perceptions of current threats and risks do not always coincide with countries” institutional views (Borges, 2016; Drent, Hendriks and Zandee, 2015). A threat is any intentional and violent event, action or event that jeopardises human lives, the unity of the international system, international peace and security (Pires, 2016; United Nations, 2004).

In view of the current security paradigm, it is therefore logical to state that new, transnational and more complex threats, like the expansion of activities associated with terrorism and transnational organised crime, the globalisation of cyber threats, the emergence of regional civil and military conflicts and natural disasters, bring to light more difficulties in terms of global peace and internal security (Bachmann and Gunneriusson, 2015; Duke and Ojanen, 2006; Feiteira, 2016; Ritchie, 2011). These transnational and hybrid threats present a high risk for a State, interfering in its functions, and have a high potential for exploiting structural and cyclical vulnerabilities. Therefore, several countries ought to establish and update national defence measures (Bachmann and Gunneriusson, 2015; Fernandes, 2005).

As for the different threats and risks to security, Borges (2016) analyses the institutional perspectives of transnational threats and risks based on a comparative analysis of the national strategies of the five permanent members of the Security Council of the United Nations (UN). Although the sample is small, the study is representative in terms of political, economic, and military weight. In this study, the author concludes that the threats of five of the members of the UN CS Council “are mostly common with regard to transnational threats, despite the different readings that are occasionally made of the same threats and the different regional and local concerns, issues directly and comprehensively related to the values, interests and political objectives of each State” (Borges, 2016, p. 48).

As Portugal is a member (founder) of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), it is also responsible for contributing to strengthening it through the cooperative defence of peace and security in the European and Euro-Atlantic regions, within the scope of its international commitments with NATO. The modern security environment contains a wide and growing set of challenges for the security of territory and populations. Citizens of allied nations depend on NATO for their defence. Thus, NATO’s essential mission will remain the same: ensuring that it remains an unparalleled community of freedom, peace, security and shared values (NATO, 2010). NATO’s current defence stance is based on an effective combination of systems, weapons and forces trained to work together seamlessly. This situation suggests that member countries must have adequate and always ready capabilities for facing these threats, and it is essential to invest correctly (Drent, Hendriks and Zandee, 2015).

At NATO level, the concept of continuing to be effective against new threats remains, identifying collective defence, crisis management and cooperative security as the essential tasks to be carried out to ensure the safety of its members. By specifying these tasks better (NATO, 2010), at the level of collective defence, it is essential to develop and acquire military capabilities to face the current threats, through multinational cooperation, to obtain economies of scale, reducing costs and providing interoperability of means. The NATO Defence Planning Process is the primary means of identifying and prioritising the necessary resources, with an emphasis on the defence industry in member countries. Adequate resources and new partners are required in times of change, namely to:

reconfigure the link between member countries against new threats and to guarantee the security of citizens;

work more closely with important international partners, namely the United Nations, the European Union and Russia, in the prevention and management of crises and conflicts;

create conditions for a world without nuclear weapons; however, if there are nuclear weapons in the world, NATO will remain a nuclear Alliance;

commit NATO to a more effective, efficient, and flexible alliance, so that taxpayers can see results in terms of money invested in defence.

The great certainty for the future is that NATO cannot depend on the power of the USA. The investment in the defence of the different member countries should be appropriate and reach 2% of the weight of the Gross Domestic Product in 2024 (Zandee, 2019).

At the level of analysis of current challenges (threats and risks) to national security and defence, the measurement variables used are those suggested either by Feiteira (2016) or by Borges (2016) in terms of the security strategies of several countries and organisations. These challenges are those contained in the Eurobarometer 432 questionnaire and are also in line with the current Strategic Concept of National Defence (Ministério da Defesa Nacional, 2013):

Public organisational performance

Performance management took on a more relevant role from the end of the seventies onwards, being seen as an integrated approach, to ensure the sustainable success of an organisation. The development of the New Public Administration was based on a variety of ideas from public management theories (Gruening, 2001; Osborne, 2006), with the aim of bridging the weaknesses and improving the strengths of business management.

With the introduction of business criteria and principles of public management, such as competition between the services provided, the increase in power and citizen participation, the public sector should be as efficient and effective as possible. These principles and ideas are emphasised by the approach called Public Value Management (PVM), in which public value results mainly from organisational performance (Moore, 2003, p. 18, 2012; Moore and Khagram, 2004; Stoker, 2006). In addition to this approach, at the level of the New Public Administration, new ways of enhancing relations between citizens and public organisations have also been seen. Responding to citizens’ preferences should be one of the current major objectives so that they play an active part in improving the quality of services (O’Flynn, 2007).

The focus of public management should be citizens, the community and civil society, so there must be a more humanistic approach and public policies favourable to democracy. In this way, a new relationship is established between the state and society (Robinson, 2015). The citizen must be valued, and must be distinguished from a simple consumer of public goods and services (Bryson, Crosby and Bloomberg, 2014; Denhardt and Denhardt, 2000).

Organisational performance is obtained when the inputs produce the quantity and quality of the desired outputs through the organisation of activities, resulting in adequate outcomes for society. Assessment of the organisations’ outcomes is the main interest of performance management (Bouckaert, 2013; Dooren, 2006; OECD, 2009). But, regarding the performance of public organisations, the inputs are difficult to measure and the outputs are hard even to conceptualise (Klein et al., 2013). For a public organisation to optimise its organisational performance, it is important to understand the inputs that go to the organisation, the outputs made based on these inputs, and the outcomes that result from being made available to the society of outputs. Good organisational performance is thus obtained through the appropriate combination of these components (inputs, outputs and outcomes), analysing the following variables (Bouckaert, 2013; Dooren, 2006; OECD, 2009):

efficiency: number of resources used per unit of service provided;

productivity: quantity of service provided per unit of resource used;

effectiveness of the service provided: number of effects or impacts on society per unit of service provided;

cost-effectiveness ratio (economy): amount of social benefit per unit of resource used.

quality: reflect the set of properties and characteristics of goods or services, giving them the ability to satisfy the explicit or implicit needs of users.

The Portuguese armed forces performance

The adoption of business principles at the level of public management implies that the public sector must be efficient and effective to improve its performance. The need for a New Public Administration focused on high organisational performance now appears as a need in terms of the literature on public administration management.

With regard to public organisations, Moore (2003, p. 18, 2013) and Moore and Khagram (2004) believes that citizens want their governments to have a combination of the following objectives that enhance public value:

high performance public services and not simply bureaucratic;

efficient and effective public organisations to achieve the desired social results;

public organisations that operate fairly and lead to fair conditions in society at large.

In terms of public organisational performance, the current emphasis is centred on the efficiency and effectiveness of the organisation and its results (Moore and Khagram, 2004). The efficiency improvement can be achieved by increasing the outputs with the same inputs (inputs), or maintaining the results with a reduction in the inputs. Such as Julnes and Holzer (2001) and Poister (2003) found that outputs are essential to achieving outcomes, with output measures being more widely used than measures of inputs and outcomes. Output measures are fundamental in the allocation of resources, in the management and monitoring of programmes and, also, in the dissemination of information for management.

The importance of achieving the right outputs (outputs) is emphasised, preferably by efficiently managing the inputs (inputs) in order to improve the results (outcomes) and, thus, bring added value to public organisations (Boland and Fowler, 2000; Webber, 2004). Organisational performance is maximised when the inputs produce the desired outputs in quantity and quality through the organisation of activities, resulting in adequate outcomes for society (Bouckaert, 2013; Dooren, 2006; OECD, 2009). Figure 1 emphasises the relationship between efficiency and effectiveness in order to optimise organisational performance at the public sector level.

The measurement of outputs has two distinct advantages, namely, it uses more general performance indicators and provides opportunities for practical learning (OECD, 2009). “Despite many uncertainties in the relationship between public sector outputs and the intended results or outcomes, measuring outputs is fundamental to any empirical understanding of performance in the public sector” (OECD, 2009, p. 43). However, the nature of the outputs is different between organisations, and should be adjusted, thus allowing to create results with an effect on society (Dooren, 2006).

The performance of the Portuguese Armed Forces is associated with the inherent fulfilment of the missions according to their Strategic Concept of National Defence (Estado – Maior General das Forças Armadas, 2018). In order to perform, it is essential to implement a capacity planning methodology, considering efficiency and effectiveness criteria i.e. how well the Armed Forces uses those resources for military purposes (Beckley, 2010). In Portugal, priority should be given to the development of capacities that contribute to (Aguiar-Branco, 2014):

participation in international theatres, within the scope of cooperative or collective security, or in an autonomous framework, for the protection of Portuguese communities abroad in areas of crisis or conflict.

national surveillance and assertion in maritime areas under national jurisdiction.

increased resilience against cyber-attacks.

the consolidation of the Portuguese Armed Forces as a modular, flexible, and modern organisation and adapting them to the new security environment, which will imply synergies in capacity building, maintaining the objective of a credible deterrent capacity.

Military defence planning for capabilities in Portugal

For public organisations, the creation, development and management of capabilities is a central point for achieving public goals (Klein et al., 2013).

In Portugal, “military capabilities are understood as the set of elements that are articulated in a harmonious and complementary manner that contribute to the realisation of a set of operational tasks or effect that it is necessary to achieve. It comprehends components of doctrine, organisation, training, material, leadership, personnel, infrastructure and interoperability” (Aguiar-Branco, 2014, p. 23657). These capabilities are the final product produced by the Portuguese Armed Forces, i.e. their output (Garcia, 2015; Santos, 2013).

The development of adequate military capabilities becomes fundamental and more important than operations in the performance of Armed Forces, allowing countries to defend themselves against threats and adversaries, national and foreign, not only to face and respond to the most likely threats and risks, but also to achieve international commitments and certain outcomes (Hannay and Gjørven, 2021; Ritchie, 2011; Tardy, 2018).

It appears that combatting the various threats and risks is one of the main priorities of Portuguese National Defence at the moment, but they are quite different, as is the way to combat them. The development of military capabilities at the level of the Portuguese Armed Forces is essential to face and respond to the most likely threats and risks to ensure the safety of citizens, ensuring one of the objectives of the current national defence policy (Garcia, 2015).

Presently, the number of personnel and the financial resources available for the development of the main programmes for the re-equipment and support of the Portuguese Armed Forces are particularly constraining. These current conditions mean that it is essential to improve organisational performance. The current Portuguese Military Defence Planning Cycle was defined through a Ministerial Guiding Directive,1.with the purpose of implementing a security planning system based on the development of military capabilities to achieve the outcomes and carry out operations. It is intended, therefore, to define the requirements of these capabilities through:

identification of gaps considered as priorities;

definition of the objectives of capabilities;

implementation and development of these capabilities;

a review of results.

In the same Directive, it is also emphasised that priority should be given to the development of capacities that contribute to participation in international Theatres of Operations within the scope of cooperative or collective security, maintaining a credible deterrent capacity and adapting these capacities to the new environment of safety.

To implement the military capabilities planning methodology and align national planning with the NATO planning cycle, the Portuguese Ministry of Defence approved another Directive in 2014, noting that the development of military capabilities is a fundamental activity in which greater effort is required. Focused on the future, the clear identification of capabilities and how to achieve them is a priority that must be integrated at different levels, always including the essential assessment of available resources and defined expenditure ratios.

The Portuguese Armed Forces should thus be able to generate and exploit the military capabilities that allow them to carry out their missions in the various general scenarios, and their employment in these scenarios must respect the priorities and guidelines contained in the Strategic Concepts (Garcia, 2015). The execution of these missions makes it possible to identify areas of potential intervention by the Portuguese Armed Forces for their defence or for capacity development. The military effectiveness of these capabilities, in addressing the most likely threats and risks and in fulfilling international commitments, becomes the outcome (Tellis et al., 2000).

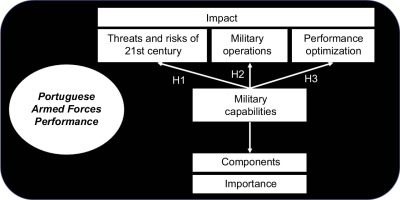

In terms of the performance of the Portuguese Armed Forces, these being a subsector of Public Administration and with a continuous need for modernisation of equipment, our research model analyses the influence that military capabilities (outputs) have on performance, in the fight against current threats and risks and through the fulfilment of the various missions (outcomes).

The research model underlying this investigation is described in the Figure 2 below, proposing the following hypotheses:

H1:The development of military capabilities has a positive effect on the combat of actual threats and risks by the Portuguese Armed Forces.

H2: The development of military capabilities has a positive effect on Portuguese Armed Forces operations.

H3:The development of military capabilities has a positive effect on the performance of Portuguese Armed Forces.

Methods

In terms of the research methodology, given the exploratory nature of this investigation, a quantitative analysis was carried out. This type of analysis seeks to determine the existence of relationships, based on the current forecast or finding of some phenomena (Creswell, 2003). At the level of quantitative analysis, univariate, bivariate and multivariate analyzes were performed (Marôco, 2014). The univariate analysis consisted of descriptive statistics (mean) regarding the importance of the various items analysed and also comparison of means of these items between the samples. For the comparison of means, the parametric t-Student test was used, being the most adequate test to analyse means of the same variable or the characteristic observed on two independent samples of individuals (Pocinho and Figueiredo, 2000).

The bivariate analysis consisted of performing correlations, using the bivariate linear correlation (Pearson’s r), to determine the strength or intensity of a linear association between the respective variables (Brites, 2016). According Mukaka (2012), correlations above 0.9 indicate a very strong correlation, between 0.7 and 0.9 indicate a strong correlation, between 0.5 and 0.7 moderate and between 0.3 and 0.5 weak.

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was also carried out (Marôco, 2014) to reduce the information inherent to the influence that military capabilities can have on the performance of the Portuguese Armed Forces. It was found that the total explained variance was greater than 60%, but that the reliability of the extraction of the constructs was acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.6). The citizens who pay for the Armed Forces should influence and indicate their needs on national basis in terms of security and defence (Ritchie, 2011). To meet the interests of citizens and the guidelines defined by the military, the sample chosen to answer the questionnaire was as follows:

a convenience sample of Portuguese Officers from various posts (115 militaries) on graduation and promotion courses that teach these topics;

a convenience sample of Portuguese citizens with a higher level of education.

In terms of the author’s questionnaires, the 7-point Likert scale was preferred in order to maximise the intended effects (Krosnick and Presser, 2010), where 1 corresponds to the lowest value and 7 corresponds to the highest value of the scale.

The answers “Don’t know / don’t answer” were considered missing values (Hair et al., 2017).

The quantitative analysis was performed using the statistical program IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0.

Results

Relatively to security threats (Table 1), according to the EFA, made to the global sample (KMO = 0.764), it was possible to ascertain two constructs. These constructs concern “conventional threats” (46.2% of the variance) and “natural and man-made disasters” (16.9% of the variance), the latter being the most important construct (mean = 6.16, σ = 0.93).

Table 1

Analysis of items and constructs for the challenges of Portugal National Defence.

The militaries differentiate these threats and their nature more, highlighting the growing importance of “conventional threats.” For citizens, although “terrorism” remains one of the most important threats, “natural and man-made disasters” (a national threat) are the second most important. The results also show that “natural and man-made disasters” should even be investigated as a separate (construct) factor, and the importance given to this threat by citizens is quite different from the importance given by the militaries (this threat is just the fifth most important for the military).

As for the Armed Forces’ missions to deal with the current threats and risks to national security (Table 2), the AFE allowed two constructs to be obtained concerning “and executing military missions” that represents 50.4% of the explained variance and the construct of “Guaranteeing the internal security of citizens” which explains 20.3% of the variance. However, from the analysis of the Portuguese Armed Forces missions that best suit national security, differences of importance have emerged between the samples from militaries and citizens. The militaries agree more with Armed Forces missions that aim to guarantee sovereignty and international peace (missions and military nature). The citizens give priority to missions to “ensure the internal security of citizens,” with a statistically significant difference between militaries and citizens (t = −3.166; p < 0.001). These types of missions present the higher degree of agreement to ensure national security and defence (mean = 6.29, σ = 0.92). So, while the militaries give more importance to missions that guarantee the national independence and international peace, citizens prioritise missions that are aimed at guaranteeing the internal security of citizens.

Table 2

Analysis of items and constructs of Portuguese Armed Forces missions.

Regarding the performance of the Armed Forces according to the current principles of the New Public Administration (Table 3), the EFA to the global sample (KMO = 0.841) reveals just one construct that refers to how the Portuguese Armed Forces act (61% of the explained variance). Acting with “efficiency” obtained a low factor loading (0.399) and is also of less importance (mean = 5.89, σ = 1.17). But there is a significant difference statistically between militaries and citizens (t = −4,171; p < 0.001). For citizens, it is one of the most important ways of acting. In developing a model of performance, the results obtained reinforce the importance of efficient management of the Portuguese Armed Forces.

Table 3

Analysis of items and constructs of Portuguese Armed Forces ways of action.

From the analysis to the importance of the various components in terms of developing military capabilities (Table 4), the results show that for both samples, personnel and training are the most important components (mean = 6.55, σ = 0.77 and mean = 6.53, σ = 0.79, respectively). This reveals the importance of building adequate military capabilities (output), with a special focus on human resources and their training.

Table 4

Analysis of items for the components of military capabilities.

The results obtained according to the correlations made (Table 5) showed that military capabilities have a positive influence in combatting current threats and risks in carrying out missions and in their performance. However, although all correlations are positive and, for the most part, statistically significant, their value is somewhat different.

Table 5

Military capabilities impact on Portuguese Armed Forces performance.

The results allow us to accept Hypothesis 1 (H1), verifying that military capabilities positively influence the fight against current threats and risks, although there are weak, but similar intensities between the correlations. There was a weak correlation between “military capabilities” and the fight against “conventional threats” (0.383) and the fight against “natural and man-made disasters” (0.414). Despite these weak correlations, the results also show that the importance given to the threat from “natural and man-made disasters” by citizens is quite different from the importance given by the military (this threat is only the fifth most important for the military). In terms of combat using military capabilities, this threat will even be considered as a construct apart.

The results obtained also allow the validation of Hypothesis 2 (H2), in which military capabilities positively influence military missions (0.668) and missions that “guarantee the internal security of citizens” (0.505). The correlations obtained between “military capabilities” and the missions to be performed were moderate, but it was possible to see that the development of military capabilities must be essential for the fulfilment of internal missions that guarantee the security of citizens and classic missions (peace and national independence).

Regarding the validation of Hypothesis 3 (H3), we found that military capabilities should also allow the Armed Forces to act in accordance with the current principles of the New Public Administration (obtained construct), with a strong correlation also being found (0.767), despite the citizens preferring the performance of the Armed Forces for efficiency, while the militaries prefer the execution of missions with quality.

As a theoretical contribution to the level of the performance of public organisations, this article shows that military capabilities (outputs) are essential to the fulfilment of missions (outcomes). These results corroborate Webber (2004), Epstein and Buhovac, (2009) and Dooren, Bouckaert and Halligan (2015).

Conclusions

The current expectations of society demand that public organisations produce better quality public services and optimise their rates of efficiency and effectiveness. In this way, the aim is to meet the guiding principles of the New Public Administration. To answer the central research problem and the respective research objectives, it was crucial to understand the interorganisational complexity of the public sector, as well as of the Portuguese Armed Forces, and trying to evaluate how this public sub-sector measures its performance. Within the scope of this “new” public administration, it is essential for the Portuguese Armed Forces to develop adequate military capabilities (output) to see the extent of its missions (outcome) to respond to the threats and risks of 21st century.

We found that military capabilities have a positive impact on the performance of the Portuguese Armed Forces, namely, in combatting current threats and risks (conventional and civil protection) and in the execution of military operations (external and internal), meaning it can optimise its performance. The performance should improve the efficiency and quality of the missions. With regard to dealing with current threats and risks, we found that military capabilities have to face “conventional threats,” as well as threats caused by “natural and man-made disasters.” These last threats are actually the most important from the perspective of citizens and they need to be seen as just as relevant. As for the missions of the Portuguese Armed Forces, military capabilities have a positive influence on the execution of military missions that guarantee national sovereignty, as well as ensure the inherent international commitments, which are the missions the military are most in agreement with. However, military capabilities must also guarantee the internal security of citizens, which citizens are most in agreement with.

The results also show that the citizens rate the performance of the Portuguese Armed Forces as efficient, while the military point to the quality of missions. This reveals the importance of the proper development of military capabilities, with a special focus on human resources.

The use of a convenience sample was a limitation because it could mean that the results are not reflective of the entire population. However, Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill (2009) consider that this type of sample is suitable for a study like this that is eminently exploratory.

With regard to the relevance of the topic, future researchers can propose an evaluation model with key performance indicators to measure the performance of the military capabilities.