Introduction

Since the 1940s, there have been over 370 recorded cases of revolutions, rebellions, protests, and civil unrest, in general. Given that a significant majority of these cases were recorded in the last decade, it is made obvious that a generalised approach for the analysis of such cases would be greatly beneficial for both academia and policy-makers. This research paper aims to accomplish the above, as presented in the research hypothesis.

The existing analytical approaches often fall short of offering a unified, multi-factor framework capable of explaining and assessing political instability across diverse contexts. Despite the existence of a large volume of relevant literature and bibliography, previous studies focussed on two specific approaches, namely examining specific cases individually, or providing a general approach that however emphasises, in most cases, a singular casual mechanism, such as economic grievances or resource availability. These approaches fail to provide a systematic analytical process that can be utilised across diverse contexts.

This study attempts to address this critical gap by combining different theoretical concepts with a strong and recognised literature background on the subject in order to produce a singular analytical framework, integrating different elements from each of the major theories. The said framework could potentially be used for both retrospective case analysis and prospective internal political instability assessment.

To this end, a brief discussion on the available literature regarding the subject is initially provided, followed by the presentation of the methodology deemed appropriate for this research. The selected cases are then analysed, and the factors influencing their occurrence are identified and cross-referenced with previously discussed literature in order to structure a generalised analysis framework.

Literature Review

The existing literature on the subject has two noteworthy aspects: Firstly, the literature addresses cases individually, documenting the events of a specific incident as well as examining the dominant events and characteristics of that incident. Secondly, there exist several theories in literature that base the emergence of movements on the analysis of a specific factor, rather than providing a universal framework for the analysis. A number of texts published in the previous century attempt to generalise the procedure of social insurgency by focusing mainly on economic and class criteria (Che Guevara, 1964; Le Bon, 1894; Taber, 1970). In addition, the predominant theories examine specific dimensions of movement formation, as discussed below.

The Social Movement Theory is considered a notable theory on the subject. While the theory is extensive in regard to the reasons for the emergence of social movements, it would be beneficial to focus on two specific structural parameters, the resource mobilisation and political opportunity processes (Klandermans and Stekelenburg, 2009). Resource mobilisation refers to the abundance of physical (such as money and equipment) and non-physical (such as organisational and recruitment strategies) resources, which make it more likely for a social movement to successfully emerge (Bob and McCarthy, 2004).

The latter identifies a number of political opportunities within a society for the emergence of social movements, such as the inability of the central government to efficiently address a situation via repression of the protestors and the external help received by some movements from foreign centres of power during their emergence (Meyer, 2004). However, the above theory fails to provide a universally accepted analytical framework, and it is argued to reflect a Western point of view regarding the social processes involved (Cox et al., 2017).

Other relevant theories include the greed and grievance theories (Murshed and Tadjoeddin, 2009). According to Collier and Hoeffler (2004), movements need to be economically viable, and their aim is mainly the redistribution of societal and economic resources. In contrast, according to the grievance theory, a movement is formed on the basis of perceived injustice and identity politics.

Specifically, there are three major subgroups of the grievance theory, namely relative deprivation, polarisation, and horizontal inequality. Relative deprivation is defined as the “discrepancy of what people think they deserve and what they actually believe they can get” (Collier and Hoeffler, 2004). Polarisation refers to the emergence of extreme intra-societal heterogeneity while simultaneous elements of homogeneity are present, for example significant discrepancies in the income distribution of the same ethnic group, which could potentially lead to sectarianism. The final subgroup, horizontal inequality, refers to the unequal distribution of resources in a way that significantly and systematically favours specific groups within a society.

A rather individualistic approach to the interpretation of social movements is that of relative deprivation, which refers to the resentment, anger, and dissatisfaction a subject might feel when comparing its situation to the objective or perceived situations of other similar subjects. This phenomenon is especially apparent in cases of unfavourable comparison, that is the subject is in a worse perceived condition than those it is compared to (Bernstein and Crosby, 1980).

Another major theory that directly correlates with the emergence of social movements is the collective behaviour theory, which refers to “relatively spontaneous and relatively unstructured behaviour by large numbers of individuals acting with or being influenced by other individuals” (Blumer, 1969). The above theory can be utilised especially in the case of mass violent protests, following a triggering societal event. Finally, a theory not directly linked to the emergence of civil unrest but, rather, to its success and continuation is that of the repression of social movements, which refers to the attempts made by the governing authority to “control, constrain, or prevent” protests (Earl, 2022).

Complimentary to the above sociological causes, new factors have been identified, emerging mainly in the 21st century. These factors stem from advancements in technology as well as societal conditions (Brannen et al., 2020). For example, the free flow of information, the impact of information and communication technology, its influence on the perception of what is considered acceptable by the population in terms of democratic values and oppression, as well as environmental stress and climate change are the issues that promote unrest globally (Brannen et al., 2020).

What is more, previously proposed models focus greatly on the theoretical–sociological interpretation of events in order to determine the causes of political instability. Therefore, they significantly lack the pragmatic approach necessary for them to be both universally accepted and useful in problem-solving and decision-making processes. An example of such a model is the Flashpoints model, which includes structural, political/ideological, cultural, contextual, situational, and interactional levels of analysis. The above model has seen criticism regarding its value for decision-making, as analysis can only be performed in retrospect (Meyer and Minkoff, 2004; Newburn, 2021).

This highlights the existence of two different analytical approaches, a prospective and a retrospective one. The more utilitarian of the two would naturally be the prospective approach, as it could be implemented in the decision and policy-making processes of politics as they evolve. The selection and analysis of the above theoretical concepts were done strategically in order to address the gaps in the fragmented literature on movement emergence. For example, the social movement theory can be utilised for explaining mobilisation incentives; greed and grievance theories integrate economic and identity-driven motives, while resource mobilisation identifies the different enabling factors of a movement’s emergence. By integrating elements of different theories into a unified framework, this study aims for a multi-dimensional understanding of internal instability by combining both structural and agency-driven explanations on movement emergence.

Research Hypothesis, Question, and Objectives

Given the above brief analysis, a tool that is able to provide a satisfactory degree of prediction and/or methodological approach for the analysis of these developments is a necessity for the modern political and security analysis procedure. It is argued that such a tool could be created through the study and analysis of various historical cases. Given the above, this paper aims to determine the factors and variables that influence the actions of various political entities.

Therefore, the hypothesis presented is that there are certain factors that influence the actions of various social, religious, state, and economic entities and compel them to act by utilising the means at their disposal to change the status quo of a system that they are part of in their favour. For the context of this research, an entity will be considered as part of the population of the state under examination, be it a religious, social, or ethnic entity, or others. Therefore, the research question is formulated to determine the factors mentioned above, while the subsequent research objective is to specify these factors by analysing relevant historical cases. The above factors can then be applied in an analytical methodology assessing the likelihood of occurrence of such events. This paper focuses on determining these factors.

Methods

The proposed hypothesis identifies a dependent variable, namely the likelihood of occurrence of the type of event described above, as well as several independent variables contributing to this occurrence. The independent variables were determined through the research methodology explained below and cross-referenced with the existing literature. All the variables involved are considered qualitatively (see Saunders et al., 2019).

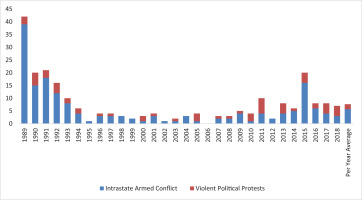

The method selected for answering the research question posed in the introduction is the qualitative comparative analysis of relevant cases. The events taken into consideration include intrastate armed conflicts, internationalised intrastate armed conflicts, and violent political protests. The time frame of the selected cases was from 1989 to 2018. The reasoning behind this selection stems from the necessity for data completeness and representativeness. Specifically, the source from which data were acquired was the Uppsala Conflict Data Programme (UCDP). The data available on the programme’s website shows the records of intrastate armed conflicts from the end of the Second World War (1946) to 2023. However, data for violent political protests was recorded from 1989 to 2019, but the cases of 2019 have not being updated for conclusion. Therefore, in order for the sample to be representative of the population under examination, the case timeframe was limited to 1989–2018. The cases were extracted from the UCDP Violent Political Protest Dataset v.20.1 and the UCDP Armed Conflict Dataset v.24.1; 230 cases were identified. The cases were categorised into three groups only, namely intrastate armed conflicts, internationalised intrastate armed conflicts, and violent political protests, as mentioned above. Furthermore, for the cases included, data must be available regarding the initiation of the conflict, which is the main interest of the research, and not their continuation. After processing the relevant data, the per-year and average distributions of the events were determined, as shown in the Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Events of interest occurring per year from 1989 to 2018 (Davies et al., 2023; Gleditsch et al., 2002; Svensson et al., 2022). Data was acquired from UCDP.

Based on the interpretation of the above distribution of events, it is made evident that globalised military and political conflicts and events greatly influence the occurrence of internal instability, as seen in 1989 and the following years (dissolution of the Soviet Union and its aftermath), 2011 (Arab Spring), and 2015 (emergence of Islamic State of Iraq and Syria [ISIS]).

The sample size was calculated based on the statistics of the overall per-year case distribution so as to provide a more accurate result. The formula used for the calculation of the sample size was that proposed for qualitative variables (see Taherdoost, 2017):

where:

Z = standard normal variate,

p = expected proportion in population,

E = precision error.

The standard normal variate for this study is set at 5% (1.96). The per-year distribution of active cases from1989 to 2018 shows a mean of 7.6667. Therefore, the expected proportion based on the assumption of an average of 186.8667 states is 0.0410. The acceptable precision is set at 10% (0.1) (Sapra, 2022). Therefore, the sample size is calculated as follows:

Having calculated an acceptable sample size, the relevant cases were then identified for analysis. The selection was random. Specifically, the cases were sorted by the year of occurrence, and each case was assigned a unique number from 1 to 230. A random number generator was used to generate fifteen random numbers from 1 to 230. Each generated number corresponds to a case from the processed data. The generator also provided a unique token for each number, which can be used to cross reference its validity. Among the fifteen cases initially selected, one case had double selection, as a number was generated twice; hence, a new number was generated in order to select a new case. Furthermore, two of the original fifteen cases did not correspond to the initiation of movements or were not documented sufficiently to provide a complete analysis; hence, two new numbers were generated in order to replace the defective cases. Based on the above, the final selection is as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of cases studied.

Each selected case was analysed based on the following elements:

Parties involved in the conflict,

Historical and political context of the conflict,

Factors contributing to its occurrence according to relevant bibliography,

Actions taken by the rival groups,

Potential external involvement in the events, and

Other points of interest relevant to the study.

The sources from which information was drawn include peer-reviewed scientific publications, public statements, and relevant historical and journalistic sources. It should be noted that journalistic sources were avoided to the highest degree possible and only included in the analysis of the last two cases, as there were no sufficient academic sources on which an analysis could be based on.

Results and Discussion

The results of the analyses agree significantly with previous literature. Specifically, the resources available to the individuals of a movement seem to greatly affect its manifestation. The government’s ability and willingness to address these situations also affect the emergence of a movement. A significant factor that was not widely discussed in previous literature with regard to its generalised significance is the role played by new technologies, namely the Internet and social media. The role of new technologies was observed as a significant factor in the majority the cases studied that chronologically belong in the last decade (2010 and onwards).

By analysing the above findings and relevant literature, it is possible to identify certain factors that were common in all or, at the very least, majority of the cases examined and appear to have contributed to the manifestation of these movements:

Relative size (RS): Relative size refers to the relative power of the entity within the system in which it is examined. The entity’s diversity, and subsequent relative size, can manifest in various forms, such as religious, social, ethnic, racial, financial, and others. The relative size of an entity can be seen as an absolute number, such as in the case of the 1997 Anjouan Secession, which was supported by the majority of the Island’s population. Also, the relative size can be seen as the relative social and physical power an entity possesses, such as in the Comorian Coup d’Etat of 1989, where a minority faction, namely the Presidential Guard, held significant power that allowed them to instigate a movement, even though they were arithmetically inferior to the rest of the society (system).

Denial of a right (DR): Denial of a right does not refer to the universally and widely accepted definition of “right.” The right in question could be an actual or perceived right that the entity considers to have been denied by other entities in the system. This could be a commonly accepted right, such as the right to life, optimal quality of life, and self-determination, but it may also be a constructed right, such as the notion that an entity has the right to be the sole ruler within the system to which it belongs. For example, the former can be seen in the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MPA) insurgency of 1990 in Mali, which involved several grievances, such as the fear of instigated policies and their effect on the Tuareg culture, corruption, and regional economic neglect. The latter can be seen in the Comorian Coup d’Etat of 1989, where the Presidential Guard did not fight for a commonly accepted right but, rather, to maintain political power and influence.

Environmental conditions (EC): Environmental conditions are defined as incidents, geopolitical conditions, and the influence of external forces, such as neighbouring states and international organisations, on the immediate regional or wider international environment of the entity, which may affect the performance of an action on its part. A positive influence of the EC factor is observed in the MPA insurgency, as various sources state that the movement had significant “external sources of support,” implying heavy involvement of Gadafi’s Libya in the training and arming of the organisation, especially through the Libyan “Islamic Legion.” In contrast, a negative influence of the EC factor is seen in the Anjouan Secession of 1997, where the international response of the United Nations (UN), France, and the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) was to condemn the secession movement.

Flow of information (FI): This factor is associated with the degree of freedom of information flow related to the emergence of the movement. Information can flow from the external environment to the entity and vice versa as well as within the elements of the entity. The freedom of the flow of information may not be subjected to strictly physical constraints, such as the Internet accessibility or owning a radio or television. However, other elements may limit the flow of information, such as the quality of information, the existence of disinformation, fake news, and the targeted presentation of news. Two prominent examples of this factor are the 1990 Civil Unrest in Kosovo and the Nepalese Revolution of the same year. In these cases, the central government attempted to restrict information flow via the closure of opposition media outlets, and reduce the effectiveness and credibility of circulating information via anti-propaganda campaigns.

Geography (GEO): Geography is defined as the factor related to the topography and demography of the area in which the movement is situated. For example, densely populated urban centres are ideal for the manifestation of violent political protests, while mountainous and jungle terrain is ideal for the manifestation of armed resistance movements. This factor is clearly observed in the 2011 Syrian insurgency, where urban centres facilitated mass protests in the early stages of the insurgency, while the rural terrain played an important role in its latter stages.

Leadership (LEAD): The factor of leadership refers to the existence of a leadership that is able to rally the population to act towards the restoration of a right that they think is being denied. The importance of a strong central or network-type leadership is observed in the cases of the Niger Delta People’s Volunteer Force in Nigeria in 2004 and the Tajikistan Civil War of 1992.

Means of projecting power (MPP): MPP is defined as the means available to the entity to ensure the satisfaction of its right. These means can include anything ranging from strikes to protests, rallies, and occupying buildings as well as arming and training individuals to conduct military-style operations.

Repression/Freedom of action (RFA): This factor includes the degree of freedom of the entity to use the means at its disposal to carry out preparatory actions for the emergence of the movement. It is worth noting that it is not necessary for these actions to be carried out with the conscious aim of initiating a movement. For example, a protest rally can develop into a mass movement. Two examples of the RFA factor include the Nepalese Revolution of 1990, where the government proceeded to arrest opposition leaders but did not outrightly ban demonstrations, and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan of 1999, where the government was unable to sufficiently limit the movement’s actions due to its ability for cross-border mobilisation.

Triggering event (TE): The triggering event of a movement is an event that is capable of starting the movement, either a single incident or a series of incidents and situations that increased tension. An example of a singular event that was sufficient to trigger a movement is seen in the civil unrest in Democratic Republic (DR) of Congo in 2016. The triggering event was the decision by the then president to postpone the upcoming presidential elections, in essence extending his term. Similarly, an example of a series of events that led to a movement’s emergence is seen in the MPA insurgency of 1990 in Mali, where a series of unfavourable political decisions, as well as previous grievances, led to the initiation of the movement.

The above factors were determined based on their relevant literature origins as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Factors to literature correlation.

Beyond the theoretical background of the factors presented above, their selection was based on their recurrence across the examined cases, as mentioned earlier, as well as their capability of being utilised in a risk assessment setting. For example, the factor “relative size” is in accordance with a number of different relevant theories, and it also allows for an analytical approach, by focusing on either the absolute population of an entity, such as in cases of social movements, or the influence of political groups, in cases of political grievances. A framework, including the above factors, ensures a multi-dimensional analysis by incorporating both structural conditions, such as geography, and agency-driven conditions, such as leadership.

A summarised analysis based on the factors stated above is provided for each selected case in Table 3.

Table 3

Per case factor analysis.

| Case | Factor analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorian Coup d’Etat of 1989 Comorian Presidential Guard (PG) | RS | DR | EC | FI | GEO |

| The PG were fewer in number compared to the tactical army, with higher military capabilities. | Perceived infringement on PG’s established rights and privileges. | History of internal political instability and limited chance of external intervention due to geography. | No significant observations. The PG had unobstructed internal flow of information. | Favourable conditions for the PG, as they were close to their objective and had little external interference. | |

| LEAD | MPP | RFA | TE | Sources | |

| The PG had a strong leadership with experience in similar situations. | The PG were sufficiently trained and armed in order to conduct the coup. | No recorded limitations on their actions. | The president’s discussions to disband the PG. | Clay, 2018; Hassan, 2009; Metz, 1994 | |

| Nepalese Revolution of 1990 Nepali Congress and United Left Front | RS | DR | EC | FI | GEO |

| Opposition had broad public support in urban areas. | Authoritarian system and restriction of political freedoms. | Internal pro-democratic sentiment and external global wave of democratisation. | Attempted “anti- propaganda” campaign by government, successfully countered by the opposition. | Urban centres as a favourable condition for organising mass protests. | |

| LEAD | MPP | RFA | TE | Sources | |

| Organisation by a central leadership of the two opposition parties. Key figures arrested or placed under house arrest. | Mass protests and civil disobedience. | Arrest of opposition members and violent counteraction. No actual banning of protests. | Arrest of opposition members and leaders, violent counteraction by security forces. | Hachhethu, 1990; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 1991 | |

| MPA Insurgency in Mali of 1990 MPA | RS | DR | EC | FI | GEO |

| Numerically smaller insurgents in comparison to the Malian military. | Existence of historical grievances, discriminatory cultural and economic policies. | Favourable internal regional and external conditions due to support by the population as well as support from external sources. | No significant observations. Potential use of informal communication networks. | Favourable conditions due to the desert region and employment of hit-and-run tactics. | |

| LEAD | MPP | RFA | TE | Sources | |

| No significant observations on central leadership. Potentially favourable due to previous military experience. | Hit-and-run insurgency tactics. | Relative inability of government forces to act on remote desert terrain. | No clear single event; rather, a combination of events leading to the emergence of the insurgency. | Ananyev and Poyker, 2023; Keita, 1998; Pézard and Shurkin, 2015; Togo, 2006 | |

| Albanian Civil Unrest in Kosovo | RS | DR | EC | FI | GEO |

| Overwhelming social majority of the Albanian population in the regions under examination. | Suppression of social, economic, and political liberties. | Favourable internal conditions in the broader context of Yugoslavia’s break up, and external conditions due to the self-determination movements following the fall of communism. | Restriction of Albanian media and publication censorship. | Favourable conditions for protests in major urban centres. | |

| LEAD | MPP | RFA | TE | Sources | |

| No significant observations on unified leadership. Later emergence of leader figures. | Means included demonstrations, general strikes, and general civil disobedience. | Significant degree of repression, arrests, and political violence from Serbian security forces. | Most likely trigger is the revocation of Kosovo’s autonomy in conjunction with general repressive policies. | Pula, 2004; Maliqi, 2012 | |

| IGLF in Ethiopia | RS | DR | EC | FI | GEO |

| Regional influence in the areas of operation. | Greater autonomy for the involved communities. | Favourable internal conditions with political instability following the fall of the previous regime in the country. | No significant observations. | No significant observations. | |

| LEAD | MPP | RFA | TE | Sources | |

| No significant observations. | Military resistance, though with potentially limited sources. | No significant observations. | Fall of regime and political transition as the main trigger. | Markakis, 1994; Ofcansky, 1993; Worku, 2017 | |

| Tajikistani Civil War of 1992 UTO–PFT | RS | DR | EC | FI | GEO |

| Opposition supported by regional factions. | Economic hardships, perceived denial of political and religious freedom, and violent government response. | Internal political instability in conjunction with regional dynamics on Islamic revivalism. External favourable conditions. | Censorship of media by both sides, including allegations of murdering journalists. | Mountainous terrain favourable for guerrilla operations. | |

| LEAD | MPP | RFA | TE | Sources | |

| Strong and unified opposition leadership. | Unhindered projection by the opposition. | Favourable conditions, including the aid provided to the opposition by external actors. | Violent suppression of protests. | Akiner and Barnes, 2001; Shapoatov, 2004; Wingerter and Speyer, 2016 | |

| Anjouan Secession in Comoros | RS | DR | EC | FI | GEO |

| Strong support base in Anjouan Island. | Perceived political and economic grievances. | Favourable regional conditions of political instability in Comoros, international unfavourable conditions. | No significant observations. | Favourable conditions due to geographical isolation. | |

| LEAD | MPP | RFA | TE | Sources | |

| No significant observations. | Utilisation of protests by the movement. | No immediate repression due to geographical isolation. | No significant observations on singular triggering event. | Cornwell, 1998; Dobler, 2018 | |

| Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan | RS | DR | EC | FI | GEO |

| Relatively small movement, with strong military capabilities. | Secular policies and denial of the more extreme Islamic doctrines. | Favourable external conditions in the region due to the activities of Islamic organisations in neighbouring countries. | No significant observations. Potential limitations due to government interference. | Favourable conditions due to mountainous terrain in the theatre of operations. | |

| LEAD | MPP | RFA | TE | Sources | |

| Experienced leadership due to participation in previous conflicts. | Insurgency and guerrilla tactics. | Relatively favourable due to cross-border movement. | Series of events regarding religious oppression, to the extent considered unacceptable by the movement. | Leusmann, 2003; Ilkhamov, 2001; Naumkin, 2003 | |

| Niger Delta People’s Volunteer Force in Nigeria | RS | DR | EC | FI | GEO |

| Significant regional influence and popular support. | Unequal distribution of oil revenue, self-determination sentiment, and economic marginalisation. | Favourable internal conditions due to already existing armed movements in the region. | Use of media by leadership to promote ideology. | Geographical conditions favourable for guerrilla operations. | |

| LEAD | MPP | RFA | TE | Sources | |

| Strong central leadership. | Utilisation of armed strikes and guerrilla operations. | No significant observations, potentially favourable conditions due to regional factors. | Government intervention for the resolution of the crisis. | Fehintola, 2020; Hazen and Horner, 2007 | |

| Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb in Mali | RS | DR | EC | FI | GEO |

| Limited size in northern Mali with no significant observations on popular support. | Religious motives and political marginalisation. | Favourable internal instability in the region and global jihadist sentiments in the sub-region. | No significant observations, potentially limited media use. | Terrain of northern Mali favourable for guerrilla operations. | |

| LEAD | MPP | RFA | TE | Sources | |

| No significant observations. | Asymmetric and guerrilla warfare tactics. | General lack of state response prior to 2009. | Absence of a specific triggering event. Continuation of strategy for establishing a Sharia state. | de Castelli, 2014; Ghanem, 2017; International Criminal Court (ICC), 2013; US Department of State, 2010 | |

| Syrian Insurgency in 2011 | RS | DR | EC | FI | GEO |

| Limited initial size, with growing support. | Political repression, economic hardships, and factionalism. | Favourable external conditions due to the Arab Spring, internal conditions due to factionalism. | Significant use of various social media platforms. | Urban centres favourable for initial protests, and rural areas favourable for insurgency action. | |

| LEAD | MPP | RFA | TE | Sources | |

| No significant observations on central leadership, potentially favourable due to military officers’ defections. | Asymmetric warfare and use of guerrilla tactics. | Initial repression of actions, which further fuelled the anti-government sentiment. | The violent repression of initial protests. | Baltes, 2016; Callaghan et al. 2014; Hof and Simon, 2013; Spyer, 2012 | |

| Secession of South Sudan | RS | DR | EC | FI | GEO |

| Significant movement in the south of the country. | Previous political grievances (First and Second Sudanese Civil War [SCW]). | Significant external (international) support. | No significant observations. | Forest terrain, favourable for guerrilla operations. | |

| LEAD | MPP | RFA | TE | Sources | |

| No significant observations. Centralised leadership in the form of major armed groups. | Both political means and guerrilla tactics. | Relative freedom of movement due to geographic division of North–South. | Signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005. | Abubakar and Yahaya, 2021; Troco, 2018 | |

| Civil Unrest in Burundi | RS | DR | EC | FI | GEO |

| Significant movement size in urban areas. | Perceived repression of constitutional freedoms. | Favourable internal conditions on the basis of historical conflict in the country, and external conditions, including imposed sanctions. | Restricted media, Internet, and telecommunications access due to protests. | Urban areas favourable for protests. | |

| LEAD | MPP | RFA | TE | Sources | |

| No significant observations. | Mass protests and strikes. | Violent response to protests by government. | Announcement of Nkurunziza’s third-term candidacy. | Arieff, 2015; European Parliament, 2015; Grauvogel, 2016; Vandeginste, 2015 | |

| Civil Unrest in DR Congo | RS | DR | EC | FI | GEO |

| Strong support in urban population. | Denial of democratic rights. | No significant observations. | No significant observations. Limitation of social media access later on. | Favourable conditions in urban centres. | |

| LEAD | MPP | RFA | TE | Sources | |

| No centralised leadership. | Mass protests and civil disobedience. | Significant government response. | Decision to extend the president’s term. | Amnesty International, 2016; Mbaku 2016a, 2016b | |

| “Free Papua Movement” (OPM) in Indonesia | RS | DR | EC | FI | GEO |

| Significant support base in areas of operation. | Self-determination of West Papua | No significant observations. Favourable internal conditions. | Use of social media and strong online presence by OPM. | Favourable conditions for guerrilla warfare due to forested mountainous terrain. | |

| LEAD | MPP | RFA | TE | Sources | |

| No significant observations. No centralised leadership. | Protests, guerrilla warfare. | Significant crackdown by security and military forces, although ultimately ineffective. | No significant observations on the 2018 incident. The trigger was the exclusion of West Papua from independence. | Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, 2015; Paddock, 2020; “Free Papua Movement” (OPM), 2024 | |

[i] RS: relative size, DR: denial of a right, EC: environmental conditions, FI: flow of information, GEO: geography, LEAD: leadership, MPP: means of projecting power, RFA: repression/freedom of action, TE: triggering event. All sources mentioned in the above table are cited in the References section of the paper.

The above factors and their corresponding literature origins can be categorised as necessary and enabling. The former refers to those that are present to a significant degree in every case under examination, while the latter refers to those that are not necessary but seem to contribute to the formation of movements, according to the relevant literature review and the analysis of the selected cases, as presented in Table 4.

Considering the above empirical analysis, the proposed methodology/analytical framework and its structural representation is formulated as follows:

When examining a potential intrastate instability, it is necessary to first correctly determine the part of the society (or entity) that is likely to make an attempt to alter the status quo due to its grievances. Thereafter, the means most likely to be used should be determined, followed by determining the existence of enabling factors and, finally, the probability of a triggering event occurring. Different elements of relevant theories can be combined for the production of a comprehensive report and internal political instability assessment, as shown in Figure 1.

Conclusions

The purpose of this research is to determine the factors that influence the actions of various social, state, and economic entities and compel them to act by utilising the means at their disposal to change the status quo of a system that they are part of in their favour. The above research objective was achieved by analysing fifteen relevant random cases and reviewing relevant available literature. The results identified nine separate factors that should be taken into consideration when analysing similar cases, namely relative size, denial of rights, flow of information, geography, leadership, means of projecting power, environmental conditions, repression/freedom of action, and triggering event; they are categorised into two main categories, namely necessary and enabling factors. While the above factors were identified across all cases, based on the analysis, their documented impact was in various degrees. This leads to the conclusion that the said factors contribute to the result cumulatively, rather than exhibiting a binary existing–non-existing model.

The importance of this study lies in the combination of different elements from various relevant theories and the development of an appropriate analysis flow chart methodology. Its main contribution is the introduction of a real-time internal political instability assessment framework. The proposed framework differs from the most existing analytical models in two ways. Firstly, it allows for prospective analysis, which is arguably the most utilitarian approach with regard to policy designing. Secondly, it is not overly technical and is deliberately kept theory-grounded, allowing it to be applied by a broad range of researchers, policy analysts, and practitioners without requiring any additional expertise. The said framework’s application could potentially extend to policy design for implementing interventions that mitigate the above factors’ escalation. Furthermore, the framework could also indicate areas for resource allocation, especially in the context of fragile states, in order to avoid societal deterioration.

Further research should be performed to verify or discredit the findings presented, as well as quantify the framework’s assessment validity, through the analysis of real-time cases, which is the framework’s main focus. Such research should also take into consideration the main limitations of the study. These limitations include the fact that the random selection methodology may have excluded cases that might be significantly different from the rest. Furthermore, future research could also help determine whether the factors identified are the actual driving force, or whether they have been overemphasised in their causality significance due to hindsight bias. All of the above limitations could be addressed through a pilot study examining the proposed framework’s validity.