Introduction

Since the 1990s, the People’s Republic of China (China, Beijing) has been increasing its global presence. As the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent economic challenges dominated the global discourse, China was seen as a natural survivor, getting out of the pandemic with minimal costs. In the meantime, China has been strengthening its security capabilities, enlarging its foreign military presence, not to mention drills with Russia, and its first overseas military base in Djibouti. New military capabilities have resulted in Beijing being more assertive, increasing China’s role as a global peace and security provider.

Africa, home to over fifty countries, remains of great interest to all major powers. Abundant natural resources, huge domestic markets, and almost infinite infrastructure needs make Africa attractive: foreign governments and companies strive for trade and investment deals and fight for the support of African countries in international organisations. China has managed to successfully compete with European and American partners, slowly building economic and political strength in bilateral relations with the continent. The last few decades have seen increased security cooperation: China has become an important small arms supplier to its African partners, organises joint exercises, and sends military instructors and military assistance on a bilateral and multilateral basis (the United Nations [UN] Peacekeeping Operations [PKO]). Last but not least is technological assistance, where China supplies satellites, constructs fiber-optic cable connections and 3G, 4G, and 5G networks as well as gives access to its most advanced technologies, such as the facial recognition and the BeiDou navigation systems. This new dimension in mutual cooperation is likely to affect the international system on different levels, that is, Africa’s increased access to new military or dual-use technologies is likely to affect the stability of the continent through strengthening the regimes. On the other hand, China’s increased military activity overseas has openly challenged Africa’s traditional partners (the United States and the European Union [EU]) and increased their efforts to deter those changes. In the long term, China’s military engagement on the continent will affect cooperation within the UN Peace corps as well as the trade flow in small arms and security technologies. The real threat lies in the character of Chinese undertakings in Africa, as many of them are supposedly of civilian character while their military use should also be taken into consideration. These shifts need to be carefully identified, researched, and analysed to foresee possible consequences for the global community.

Sino-African security ties have been subject to many analyses. The majority of authors concentrate on Chinese arms exports (Byman and Cliff, 1999, 2019; Eisenman, 2018; Hull and Markov, 2012; Tian, 2018) and the significance of the Djibouti military base (Cabestan, 2020b; Downs et al., 2017, Wang, 2018), China’s contribution to peacekeeping efforts on the continent (Alden, 2014; Alden and Large, 2013), Beijing’s role in conflict resolution in South Sudan, Mali, and Chad (Benabdallah and Large, 2020; de Coning and Osland, 2020; Lanteigne, 2019; Large, 2008), disputes over China’s non-interference principle in Africa (Aidoo and Hess, 2015; Hodzi, 2019; Moradi, 2019), and debates over Beijing’s response to the Arab Spring in Libya (Ding, 2016; Zerba, 2014). Polish authors focus on Chinese energy investments on the continent (Gacek, 2012; Kozłowski, 2013; Krukowska, 2014), its economic cooperation with Africa (Cieślik, 2012; Kostecka-Tomaszewska et al., 2018), and political approaches to its African partners (Firmanty, 2013; Mierzejewski et al., 2023; Pietrasiak and Mierzejewski, 2012). More subtle forms of China’s engagement in Africa are only rarely recognised as security engagement, such as investment in telecommunication sector and the use of facial recognition in smart city systems (Feldstein, 2020, Hawkins, 2018; Meservey, 2020; Weber and Ververis, 2021), the spread of Chinese fiber-optic cable network or the popularity of BeiDou, and China’s navigation system (Aluf, 2023; Blaubach, 2022; Grassi, 2014). The only thorough analy-sis of China’s security engagement in Africa was recently published by Eisenman and Shinn (2023). With the increased dynamic of China’s rising assertiveness, the lack of proper recognition of Chinese security-related undertakings in Africa may lead to possible future threats being ignored.

This paper seeks to fill in the gap by identifying and describing a vast variety of instruments used by China in its evolving security cooperation with Africa. The research objective of the paper is to point out and understand the nature and scope of Chinese versatile engagement in peace and security issues on the continent, based on its activity through international organisations, such as the UN peacekeeping missions and its involvement in African politics, with a particular focus on technological cooperation in security-related issues (satellite cooperation, nuclear cooperation, information technology, cybersecurity, and surveillance techniques). The hypothesis of the paper is that China’s increasing security engagement in Africa is a consequence of Jinping’s (2017a, p. 529) goal of achieving a “community of shared future for mankind,” a sphere of influence that will allow China to increase its role in global affairs. By its involvement in security-related cooperation with the continent, China intends to secure its vital political and economic interests and strengthen its image as a responsible global power. African partners therefore need to make necessary efforts to avoid being locked between competing powers and manage their security in an equitable manner. The paper makes three contributions: first, it outlines the origins of Sino-African security relations in China’s strategies and strategic papers. Second, it identifies and describes all faces of Chinese security engagement on the continent. Lastly, it offers advice to African governments on how to avoid dangerous dependence on foreign security providers.

Through extensive literature analysis, with special focus on primary sources, and logical reasoning, the author intends to identify the new dimensions of Sino-African security cooperation and define the diverse implications of China’s new role as a regional security provider.

China and Africa: A sustained relationship

Sino-African cooperation dates back to the 1950s when cultural and military relationships were established. The region is politically and economically diversified: while cooperation is thriving in Sub-Saharan Africa, Beijing’s interests and influence was limited in Northern Africa, traditionally more bound to European or American partners. China has diplomatic and economic relations with all but one country (Eswatini), although Beijing focuses on countries with geographical advantages, geopolitical and economic importance, or strategic mineral resources, such as Ethiopia, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Angola, and Sudan (US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, 2020, p. 140). Bilateral relations are based on strong political and economic ties. Chinese scientists admit that Africa’s political support in the international arena constitutes a significant component of China’s global power and influence (Yu, 2018, p. 489). The continent is abundant in many resources, such as oil, cobalt, copper, platinum, cocoa, and tobacco, all needed by China’s industry and consumers, as well as large markets, attracting Chinese suppliers.

China’s relations with Africa have always had a security dimension, although of changing quality. For a long time, it was limited to sending military instructors and small arms sales to address inter-state security problems (Meservey, 2018). In response to new threats, such as terrorism, China has modified its approach: deepened its security ties with the continent by diversifying engagement under direct and indirect contributions to Africa’s peace and security challenges (The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2015a). Direct contributions include military assistance in the form of troops sent at the request of the UN and interested countries, and medical and engineering instructors, equipment, and arms sales. Indirect contribution is technological sharing, adding to narrowing the gap between the developing countries of Africa and advanced economies. A new dimension was added when Africa joined the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), as China’s infrastructure investment requires increased long-term stability.

In its quest for security cooperation, China faces competition from traditional security providers, such as France or the United States and new security actors, such as Russia, represented by the Wagner Group (Duggan and Hodzi, 2020). This situation derives from China’s recent growing ambitions and capacity to increase its security activity on the continent. The Chinese engagement in Africa’s security is not a result of its compassion. Instead, China has been using its African partners to achieve more significant gains—securing its vital national interests: the access to African mineral resources (i.e. oil, cobalt, copper, platinum, and uranium) and internal markets, and support in international organisations that eventually solidifies China’s great power status.

Security in China’s foreign strategy towards Africa

China wants to regain its proper place in the international system in the 21st century. Many scholars therefore believe that China should build up its international credibility, through providing security and economic benefits to other nations, as a prerequisite on the way to establishing a leading world power status (Yan, 2014, pp. 160, 182). Instead of keeping a low profile and avoiding confrontation, China has implemented an assertive foreign policy to strengthen its image and position abroad in order to create a “more reasonable and fairer” world order (Jinping, 2017b). China intends to be a “stabiliser” of the global political and economic system, hoping to win support from developing countries whose voices should be better heard and their roles expanded (Fan et al. 2017, p. 22; Feng et al., 2017, p. 63).

President Xi Jinping has modified China’s foreign strategy in line with the above. The concept of the “community of shared future for mankind,” mentioned by Xi Jinping for the first time in Moscow in 2013, and repeated in January 2017 during the World Economic Forum at Davos, won high credits abroad. Xi Jinping’s idea is based on the construction of a new type of international relations with China at the centre (Gao, 2023). Some authors argue that this concept includes military cooperation (Yan, 2014, p. 169). In its expansion strategy in Africa, China has moved from mainly economic goals to political ones, using economic, political, cultural, and security instruments.

Africa is a natural partner in Beijing’s mission. Tragic colonial experience marked with slavery and impoverishment resulted in chronic underdevelopment and instability that condemned Africa to a distant place in the US-dominated world order. China emphasises the similarity of their fates and the complex history, and offers guidance and help on the way to development. Through years of diplomatic efforts strengthened by financial assistance, China has become an internationally respected investor, trade partner, and mediator involved in conflict resolution processes on a bilateral basis and under the auspices of the UN.

Beijing’s new foreign policy is reflected in strategic documents. In a 2013 White Paper, China pledged to play an active role in international political and security fields, such as UN peacekeeping, disaster relief, humanitarian aid, counter-piracy missions, and joint training and exercises (The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2014). In the 2015 Military Strategy, China admitted that with the growth of its national interests, its national security and the security of overseas interests have become an imminent issue (The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2015b). The 2019 White Paper on Defence confirms that China’s overseas interests “endangered by international and regional security threats” are a crucial part of the country’s national interests (Grieger and Claros, 2019, p. 6). Beijing has pledged to use its armed forces to “fulfil their international responsibilities and obligations and provide more public security goods to the international community.” The interventions undertaken include UN peacekeeping and vessel protection operations, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, cooperation in arms control, and non-proliferation. China also intends to increase its involvement in the settlement of hotspot issues, to protect the security of international passages, and to respond to natural disasters and threats of terrorism and cyber security (The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2019).

China’s activities in Africa have also evolved. Due to the high level of instability in the region, China has enriched its economic and political engagement with a security dimension, institutionalised through the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). Security issues were included in the 2012 Action Plan when the China-Africa Cooperative Partnership for Peace and Security was launched. Beijing has expressed its commitment to strengthening cooperation in policy coordination, capacity building, preventive diplomacy, PKO, post-conflict reconstruction and rehabilitation, and illegal trade in small arms and light weapons (Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, 2012). In 2018, peace and security cooperation was identified as one of eight major initiatives for the next 3 years and beyond. In addition, China promised to launch fifty security assistance programmes to “advance bilateral cooperation under BRI, and in areas of law and order, UN peacekeeping missions, fighting piracy and combating terrorism” (Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, 2018). Other pledges included launching the China-Africa Peace and Security Fund, supporting Africa’s capacity-building for independent peacekeeping missions, and military assistance to the African standby force and African capacity for immediate response to crisis. A new platform of cooperation was introduced in 2019—the China-Africa Peace and Security Forum, where defence ministers and military representatives discuss the most urgent security issues. Unfortunately, information about detailed military cooperation with African partners is scarce; therefore, we can presume that the pledges are followed through with little specific data considering African partners. According to Eisenman and Shinn (2023, p. 55), “Africans tend to speak favourably about the FOCAC.”

Since 2021, Beijing has underlined the need to give African partners more say in security issues. In a White Paper on cooperation with Africa, China declared that its military cooperation with the continent is aimed at promoting security and stability while championing the principle of “African people solving African issues in their own ways” (The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, 2021). Simultaneously, Beijing underlines that bilateral and multilateral security cooperation within the African Union will continue to be based on the non-interference principle and shall respect the will of African countries. The will was repeated in the Global Security Initiative concept paper, where China called for adapting to new challenges through solidarity, addressing traditional and non-traditional security issues with a win-win mindset, and creating a new path to security that features dialogue over confrontation, partnership over alliance, and win-win results over zero-sum game (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 2023).

Military diplomacy

In line with a new focus on security cooperation with Africa is Beijing’s military diplomacy, such as high-level visits, bilateral agreements on defence and military cooperation, and arms trade. Although Africa is behind Asia and Europe in China’s military engagement, as a sign of commitment to bilateral cooperation, Beijing has increased the number of military attachés stationed on the continent to twenty-seven (Baike.baidu.hk, 2023). In 2022, China appointed an experienced diplomat as its first special envoy to the Horn of Africa to promote the “peaceful development” of the region torn by conflicts (Reuters, 2022).

The UN peacekeeping programme is the most significant platform of China’s security engagement in Africa. In the last few decades, Beijing has intensified its assistance: since 1990, more than 30,000 personnel from China have been deployed in Africa, which constitutes 80% of all Chinese peacekeepers sent in the PKOs. In 2023, China was the second financial contributor, providing 15.21% of the budget, and the ninth contributor with 2,277 military and police personnel, more than double the combined total of the other permanent members of the UN Security Council. Over 1,000 troops from China are deployed in South Sudan (UNIMISS), 409 in Lebanon (UNIFIL), and 397 in Mali (MINUSMA), with additional personnel in Western Sahara, Middle East, and Cyprus (United Nations Peacekeeping, 2023). The Chinese personnel include combat troops, force protection soldiers, medical personnel, military engineers, logisticians, and staff officers (Dyrenforth, 2021). China’s engagement goes further: since 2008, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy (PLAN) has been dispatching convoys to the Gulf of Aden as part of counter-piracy operations, protecting over 7,000 Chinese and foreign vessels. Beijing also helps to combat the insurgencies and armed groups that stand behind the instability of certain regions, such as Boko Haram in Nigeria. China’s engagement also has a medical factor: during the COVID-19 pandemic, China submitted 300,000 doses of vaccines to UN peacekeepers (The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, 2021).

Nevertheless, despite its undoubted merits, the deployment suggests that China is far from a benevolent contributor. The most significant number of Chinese peacekeepers is stationed in South Sudan, protecting the oilfields owned by China National Petroleum Corporation. In other words, through its engagement in the UN peacekeeping forces, China has secured its investment (Eisenman and Shinn, 2023; Lynch, 2014). More active contribution to African security gives the Chinese soldiers valuable experience, operating overseas in more or less hostile environments. According to Bo (2019), a retired Chinese PLA officer, Africa is a “test lab” for China, where it can get military experience without giving up on its non-interference principle. The modernising PLA can test new equipment, improve its logistical capabilities and lines of communication, and train soldiers in combat and non-combat operations. The soldiers learn to cooperate with foreign peacekeepers and overcome language barriers (Cabestan, 2018). Everything is done under the UN brand, yet increasing China’s strategic influence and power.

The Chinese forces stationed in Africa help to improve China’s image and extend its diplomatic outreach. Until recently, the Chinese troops were isolated from local communities, but are now involved in medical assistance, infrastructure construction, school support, and social activities, such as sports. China has also learned from previous experience and is now avoiding any ambiguity in military engagement: its impact on fuelling conflicts in South Sudan, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Somalia is not being repeated now (Eisenman and Shinn, 2023). Building trust among Africans is a foundation for future economic and political engagement. Security cooperation with African partners allows China to win the hearts of its citizens and gain support from their governments, which is proven by increased economic and political ties with countries that have the strongest cooperation with Beijing. China cashes in this support when there is voting in international organisations over sensitive issues, as in the case of the UN Human Rights Council resolutions condemning abuses that have never targeted China (Raess et al., 2017; The Economist, 2022). Increased protection of the once neglected Chinese diaspora in Africa further strengthens the international image of a responsible global power. Thus, since the Arab Spring of 2011, the PLA has conducted several successful evacuation missions of its citizens from conflict areas (i.e. Libya).

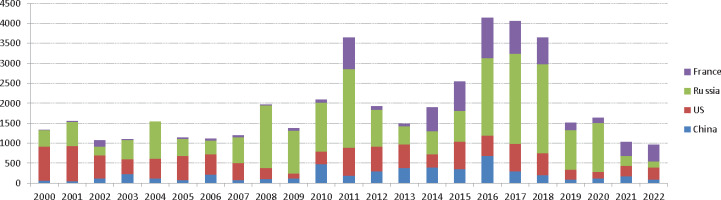

Peacekeeping operations are also an excellent reason to start bilateral military cooperation. China establishes ties by donating military equipment transmission systems and funding personnel training programmes through workshops and scholarships (Devermont, 2020). Of special importance is trade in arms, although its volume remains surprisingly low: according to Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI, 2023a), between 2000 and 2022, China’s arms exports to Africa were the smallest of the three top suppliers: Russia, the United States, and France, accounting for only 11% ((trend-indicator value, TIV) 5 billion) (Figure 1).

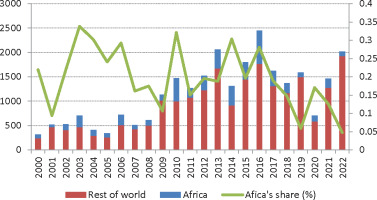

By the end of the first decade of the 2000s, Beijing had increased its global arms exports, although the volume and share of African imports remain low. The peaks in 2010 and 2016 were due to the sales of tanks (Morocco) and multiple rocket launchers (Algeria) (Figure 2; SIPRI 2023b).

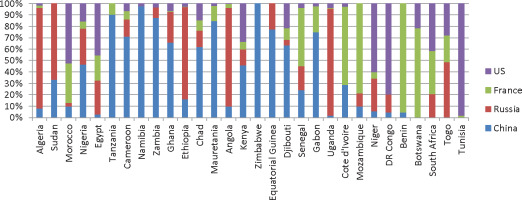

In Africa, the six largest recipients took more than 70% of Chinese arms exports to the region: Algeria (23%), Sudan, Morocco, Nigeria, and Egypt (10% each), and Tanzania (9%). However, given the volume of arms exports, China remains a small supplier even for its largest partners, giving way to Russia and the United States (Figure 3).

A recent report by the Atlantic Council found a positive correlation between investment and arms supply in cooperation with China (Mohseni-Cheraghlou and Aladekoba, 2023, p. 13); hence, once again Beijing’s economic interests are covered. In an era of increased economic uncertainty, China has never given up on its rising global ambitions and its strategic interests in Africa.

The primacy of national interests in Beijing’s security activity in Africa has become apparent with the intensification of cooperation under BRI launched in 2013. The BRI aims at infrastructure construction to stimulate the economic development of Third World countries; thus, China’s contribution to Africa’s development and increased stability, hence security. Within the BRI, China has extensive investment in transportation infrastructure in East Africa, notably in Ethiopia and Kenya, where peacekeeping forces in South Sudan ensure the stability of the region with sizeable Chinese investment. The same reason stood behind counter-piracy patrols in the Gulf of Aden, where the PLAN’s presence protects the sea lines of communication and guarantees China’s energy security (Saunders, 2023, p. 14). Through the BRI, Beijing has increased to forty-six, the number of ports leased, operated, or constructed by Chinese companies (Devermont et al., 2019). China has also intensified its military presence abroad by opening its first military outpost in Djiboutiin in 2017, overlooking the Gulf of Aden and the strategic Bab al-Mandab Strait leading to the Red Sea. The base is an important trade port and has also increased China’s opportunities to collect intelligence on nearby US military facilities in Camp Lemonnier and American operations in Djibouti and the surrounding area (Gunness, 2023, p. 37). Beijing seems to be cashing in its engagement in Africa: China plans to build additional military facilities overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, most probably in Equatorial Guinea (Vergun, 2022). The BRI might also play an essential role in China’s global expansion should the PLA use military diplomacy to build security capabilities in countries with BRI investments (Heath et al., 2021, p. 157).

China’s security engagement in Africa helps to expand its diplomatic influence around the world and become a key player in global affairs as well as the self-appointed leader of the “Global South” (US Department of Defense, 2023, p. 13). China has been positioning itself as a leading peacekeeper, seeking to shape international norms and determine political outcomes within the UN system (Bayes, 2020). Backed by African partners, Beijing has been increasing its influence in the UN: in 2021, Chinese delegates headed four out of fifteen UN specialist agencies (Food and Agriculture Organisation [FAO], International Civil Aviation Organisation [ICAO], International Telecommunication Union [ITU], and International Labour Organisation [ILO]), thus enabling China to influence such vital regional issues as food shortages and international air navigation. Director-General of the World Health Organisation (WHO) is T.A. Ghebreyesus from Ethiopia, China’s most loyal African partner. Those appointments are crucial: during the COVID-19 pandemic, because of Chinese pressure, Taiwan was excluded from ICAO safety and health bulletins as well as the WHO’s emergency meetings. It seems that the ultimate goal of Beijing is the control of institutions (e.g. the UN Human Rights Council) and shaping the new directions of cooperation, with a focus on state-led development and economic growth and lesser importance on political reforms and democratisation (Wong and Li, 2021, p. 132). Many authoritarian regimes find the Chinese governance and development model attractive. Its rising popularity will not necessarily increase security in the region but it will give Beijing substantial political leverage.

Despite the obvious benefits from China’s peacekeeping activity on the continent, African countries should separate security and economic interests, and allow a greater presence of other peacekeepers. Further regionalisation of security efforts should proceed in order to give African partners larger agency.

Security aspects in technological cooperation

In the 21st century, information and communications technology (ICT) has become a critical factor in economic development (Vu, 2011). Africa has a significant technology gap that cannot be narrowed without the help of advanced economies. The continent’s enormous potential was noticed in Beijing. Cooperation in the ICT sector is conducted under the Digital Silk Road (DSR), a component of BRI, helping underdeveloped countries to improve telecommunications networks, artificial intelligence (AI), cloud computing, surveillance capabilities, and construction of cross-border and transcontinental fibre-optic networks and submarine sea cables (Kurlantzick, 2020; Kurlantzick and West, 2021; Rolland, 2015). Technological cooperation, however, carries the risk of sensitive data transfers, giving China leverage over western competitors in access to information.

China supports Africa in digital transformation by offering the BeiDou satellite navigation system as a global alternative to the American Global Positioning System (GPS) network and the European Galileo system. BeiDou is a component of the Space Silk Road, aiming to develop China’s space capabilities by constructing a network of satellites and ground infrastructure. In November 2021, the first China-Africa BeiDou Forum on Systemic Cooperation took place in Beijing, bringing together 600 representatives from fifty African countries. The system is offered free of charge, and its coverage is exceptional: as many as thirty BeiDou satellites transmit continuous signals to Addis Ababa (Ethiopia)—twice as many as the American GPS (Tsunashima, 2020).

Chinese companies are present in all areas related to new technologies, especially in the telecommunications sector. Transsion Holdings, based in Shenzhen, had 49% of the African mobile phone market in 2018 (Williams, 2019). The success of Chinese feature phones comes from their quality, comparable to western ones, and the fact that they are better suited to the African markets in terms of price and adaptability (Deck, 2020). China has also engaged in the construction of cellular networks across the continent. According to reliable data, Huawei alone has built 70% of 4G network stations in Africa, and is also involved in the construction of 5G networks in Ethiopia, Kenya, South Africa, and Uganda (Kidera, 2022). The advantages of Chinese corporations result primarily from their price competitiveness due to state subsidies (Fuller, 2016, p. 85), and the control of the telecommunications sector gives China access to high quantities of data (Basin et al., 2018), undermining the national security of African partners and their allies.

The construction and control of submarine fibre-optic cables, transferring financial data, diplomatic messages, and military orders constitute a significant threat to global cybersecurity. Nowadays, it is the United States that controls most of the undersea fibre-optic cables that handle about 95% of intercontinental data flows (Page et al., 2019). Beijing considers submarine cables as strategic assets that can be tapped or severed during a time of conflict (Kraska, 2020). As part of the DSR, China has initiated the construction of its transnational network infrastructure through underwater, terrestrial, and satellite connections, mainly with BRI countries. In order to independently manage the flow of data and information, Huawei and ZTE have already laid fibre-optic communication and e-government networks in over twenty African countries. Chinese companies have been implementing large international projects for laying submarine cables: SeaMeWe-5 (connecting Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Western Europe, and Africa), Africa Europe-1 (from South East Asia to Europe via Egypt), SAT3-WASC (connecting South Africa and Portugal along the western shore of Africa), and the 45,000-m long 2Africa (connecting Africa and the United Kingdom) (TeleGeography, 2022). The primacy of China’s interests is visible in other sectors of technological cooperation: as submarine cable connectivity is critical to the economies of coastal countries, they risk disruption of connectivity if they pursue policies unwelcome in Beijing (Burdette, 2021).

A new field of bilateral cooperation is the nuclear sector. China has initiated strategic ties with countries abundant in uranium (South Africa, Namibia, and Niger) or having advanced nuclear energy programmes (i.e. South Africa, Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, Kenya, Uganda, and Nigeria). Despite fierce competition from Russia, China has manged to win future contracts for supplying expertise and services (Chimbelu, 2019).

Thanks to cooperation with African partners, China has successfully competed with the United States in facial recognition technology development, key in surveillance systems. In Africa, countries use CloudWalk, Hikvision, and Huawei facial recognition technology in smart city systems, and data obtained from millions of Africans helps to improve the Chinese AI in recognising the voices and faces of various ethnic groups (Hawkins, 2018). To mention a few, the Chinese system is used in Johannesburg, Nairobi, Accra, and Kampala (Feldstein, 2020). The access to data from millions of unaware Africans gives China an advantage over its western competitors that have limited access to sensitive data.

China’s security interests in technological cooperation are apparent. According to Benabdallah (2020), China’s rising military cooperation with Africa aims at technology sharing with African partners to increase their dependence on China and spread Chinese technologies worldwide. The widespread use of Chinese technologies in Africa entails their recognition by the ITU as technology standards that will challenge western ones. Hence, in September 2020, China adopted a new concept: Global Initiative on Data Security, attempting to “contribute Chinese wisdom to international rules-making” on data governance (Tiezzi, 2020) to control the narrative on data security issues and shape global norms. Strengthening cooperation in information technology and cybersecurity also aims to control the flow of information to “push China’s Internet governance proposal towards achieving international consensus” (Kania et al., 2017). New technologies developed or improved, thanks to cooperation with Africa, push out western competitors and give access to markets to Chinese producers. Under the pressure of a post-pandemic economic slowdown, the world’s largest exporter cannot miss this opportunity.

In security, the popularity of the Chinese digital equipment distributed in Africa may pose crucial cyber threats to African governments and their partners in Africa and elsewhere as they enable espionage and sabotage. Submarine cables, navigation systems, and telecommunication stations constructed and owned by Chinese companies financed by BRI loans are very insecure, given China’s policy towards gathering and controlling data (biometric data included), operations, and digital infrastructure management. The role of Chinese companies involved in Africa’s technological development is unclear. Despite assurances of their autonomy, under the 2017 National Intelligence Law, all Chinese companies are required to “support, assist, and cooperate with state intelligence work” (Tanner, 2017); hence, the real danger of data leaks and “back doors” in telecommunications infrastructure. African countries should at all costs avoid being locked between competing powers: the United States, the EU, and China. Increased self-reliance in security issues, building regional cooperation, and increased public investment in digital development, from research to construction of digital infrastructure, should help reduce external risks. Diversification of partners is a means of securing greater agency in vital security issues.

Case studies: Ethiopia, Djibouti, and South Africa

One of the most prominent examples of China’s security engagement is Ethiopia—an important member of the African Union, with a strategic location in East Africa and a large population and internal market. China established diplomatic relations with Ethiopia in 1970, and they were upgraded to a comprehensive strategic partnership of cooperation in 2017. In 2005, a Sino-Ethiopian cooperation agreement was signed regarding the training of troops, the exchange of technologies, and joint peacekeeping missions. China sent its peacekeepers to Ethiopia in 2000–2008. Ethiopia cooperates satisfactorily with China within the FOCAC structure (Eisenman and Shinn, 2023, pp. 55, 217, 218) and has been developing its Internet system based on Chinese technologies (Meester and Lanfranchi, 2021). Partners develop technological cooperation: China has launched two Ethiopian satellites (in 2019 and 2020), co-funded by Beijing, and continues its engagement in the development of the Ethiopian space programme by training specialists (Klinger and Oniosun, 2023). Ethiopia has developed its telecommunications network with the help of Chinese suppliers and grants (US$1.9 billion) and purchased surveillance equipment to increase control of the opposition (Jili, 2022). China has been a role-model for the government of Ethiopia in digital transformation (Xinhua, 2024). Ironically, Ethiopia has been—indirectly—subject to Chinese surveillance when the African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa was compromised prior to 2018 (Tilouine and Kadiri, 2018).

Djibouti is strategically situated on Africa’s eastern shore, overlying the routes of communication with Europe and the Middle East. Djibouti has signed a military cooperation agreement on small-arms training and has been a part of senior-level cooperation. Both countries have their military attachés. By diversifying its political and economic partnerships, Djibouti has managed to exert some agency towards China (Cabestan, 2020a, p. 15). Yet, China has deep involvement in financing the infrastructure development, for example, the Addis-Ababa–Djibouti Railway and the Doraleh Multipurpose Port (Elmahly and Sun, 2018). Djibouti is home to the first Chinese military base overseas (Cabestan, 2020b), adjacent to Doraleh Multipurpose Port, administered by China Merchants Group. This strategic location, close to military bases belonging to the United States, France, and Japan, not only gives the Chinese navy the possibility to replenish supplies but also offers the possibilities to train the troops and test the equipment in unfamiliar conditions (Eisenman and Shinn, 2023, pp. 289–290). China also offers medical support by sending medical teams—by the end of February 2023, they had provided 14,658 outpatient services, 576 emergency services, and completed 1,168 surgeries (Xinhua, 2023) and Peace Ark, a navy hospital ship. The PLAN has made many port calls in Djibouti during its antipiracy actions in the Gulf of Aden. According to Eisenman and Shinn (2023, p. 282), two-thirds of China’s naval ship visits were at Djibouti, supporting its importance for China’s strategic goals in Africa.

Cooperation with South Africa, the continent’s most advanced economy, has many dimensions. Beijing, as an important arms exporter, is active at the Africa Aerospace and Defence Expos, where the Chinese companies showcase missiles, vessels, aircraft, and unmanned aerial vehicles that can cover the needs of navies, ground, and air forces of African partners. As the largest foreign exhibitor, China ensures it can deliver entire national defence systems to increase regional peace and stability (Global Times, 2018). Industrial cooperation is developing as South Africa hosts major Chinese IT companies, such as Huawei, ZTE, and China Mobile International. Military exchanges include high-level military meetings as well as joint research, visits, and training of South African officers in Chinese military academies (Eisenman and Shinn, 2023, pp. 217–218). The South African navy twice (in 2019 and 2023) conducted drills with its Russian and Chinese counterparts (Ray, 2023). Over the years, South Africa has signed numerous energy cooperation agreements, also covering nuclear technology (Mukherjee, 2023). According to Eisenman and Shinn (2023, p. 282), since 2000 there have been nine naval ship visits of the Chinese PLAN, which places South Africa just behind the leader—Djibouti. China has also used soft power capabilities to strengthen bilateral relations: South Africa hosts the largest number of Confucius Institutes on the continent (six); there are various Chinese cultural (e.g. Chinese New Year and cultural exhibitions) and education programmes, and South Africans use Chinese applications on social media and for payment and banking services. During the COVID-19 pandemic, China shared with its South African counterpart personal protective equipment, vaccines, and knowledge (Akinola and Tella, 2022).

Conclusions

In the last few decades, President Xi Jinping has been successfully implementing his foreign strategies in order to increase China’s role in global affairs through economic cooperation, political partnership, and security alliances. The world has therefore seen an incredible increase in China’s cooperation with Africa, where investment and trade were followed by Chinese nationals seeking their share in Africa’s development. Continued interactions between China and its regional partners have led to increased connectivity and interdependence, with intensifying security cooperation. China’s security activities in Africa include direct military involvement in UN peacekeeping missions and small arms exports, while indirect contribution focuses on technology-sharing, where African partners have gained access to Chinese new technologies at the cost of over-reliance on Beijing. Both forms of cooperation seem to perpetuate an asymmetry between the partners, with most of the benefits accruing to China, while Africa inevitably becomes even more dependent.

China’s engagement in Africa’s security helps to advance its vital economic and political interests: it secures access to African mineral resources and internal markets, and supports in international organisations that will eventually help solidify China’s great power status. Beijing’s approach is based on the western strategy of using cost- and risk-effective alternatives to military interventions in issues of national interest. PKOs have undoubtedly increased peace and stability in Africa, while technological cooperation mainly benefits China, helping Beijing to catch up in the global technological race, thanks to data and information gathered in Africa. Thanks to financial investments and trade, China has its share in stabilising the African development process and indirectly adding to regional security. At the same time, China’s military engagement has weakened African ties with western democracies and reinforced regional regimes.

African partners welcome China’s security engagement on the continent. The Chinese forces stationed in Africa help to prevent conflict escalation, and technological cooperation enhances African comprehensive economic development. China’s increased financial engagement makes development challenges easier to meet, especially with insufficient European and American development aid. At the same time, Africa needs to reduce its dependence on China by promoting regional cooperation by diversifying suppliers and investors in key security sectors. Active participation in new standards development will help to regain digital independence and sovereignty.

However, Africa’s western partners should increase their security engagement in the region to control China’s activities and manage Beijing’s global influence. Unbalanced political, economic, and—especially—technological cooperation with Chinese companies should bring the increasing dependence and limited autonomy of not only African partners but also their European and American allies. China’s increased activity in Africa will ultimately undermine the western global security system and long-term security implications of Sino-African security cooperation might be of crucial importance for the stability of the international system as a whole. Therefore, increased American and European security commitment should follow Beijing’s involvement.