Introduction

Maintaining morale in military operations is a vital element in maintaining the resilience and determination of members of the armed forces. Key aspects of this support include developing strong interpersonal relationships and a team culture. Public recognition of individual and collective achievements not only increases satisfaction but also boosts troop morale. Ensuring adequate access to quality equipment and adequate living conditions is a critical contributor to the well-being and morale of military personnel. Efficient logistics and adequate supply are key factors in ensuring the resources needed to successfully complete missions. Providing effective means to maintain contact with families contributes significantly to the emotional well-being of service members. The implementation of psychological preparedness and resilience programmes has an essential role in managing stress and trauma. A deep understanding of the purpose and importance of the mission plays a crucial role in supporting morale by providing a clear and motivating purpose. The comprehensive approach to combat morale covers social, psychological, and logistical aspects, thus creating a favourable environment for the optimal performance of military personnel’s activities.

Morale influences combat power, based on the military and their will, consisting of persuading the armed forces. The assessment of this combat power depends on the morale of the troops and the beliefs of the combatants. To strengthen this, proper motivation, effective management, and appropriate leadership are required. Combat power is influenced by both static factors, such as the human element, and dynamic factors, such as army morale, essential in achieving great combat power within the military structure.

The motivation of military personnel, at both individual and collective levels, is a fundamental basis of morale. Changes in internal states lead to changes in external reality. The concept, derived from World War II, that physical reality can be influenced by thoughts, beliefs, and expectations, illustrates how attitude significantly affects a soldier’s overall state of mind, and their emotional and mental state is essential to maintaining balance in difficult situations.

The study analyses the role of morale in the management of stress during war or on the battlefield, with the objective of identifying perceptions and representations about the importance of this mechanism in the aforementioned environment and identifying possible solutions to improve it for soldiers deployed on the battlefield. A mixed-methods approach was adopted to explore the factors that influence military engagement under combat conditions. By using both qualitative and quantitative analyses, the research aimed to answer the following question: “Does military morale significantly affect combat power in the context of hybrid warfare?” These results confirm the importance of morale in achieving combat power while also highlighting the need to integrate a military resilience module into the initial and continuing professional training of military personnel.

The paper is structured in the following sections: Section 2 presents a brief overview of the concept and sociological studies relevant to this topic; Section 3 investigates the impact of morale in supporting conflict resolution efforts and details the research methodology; and Section 4 discusses the conclusions derived from the study.

Conceptual approaches to military morale

The development of military resilience focuses on amplifying the strengths soldiers possess but especially on managing the negative effects that the battlefield and the execution of missions have on them. The morale of the military is represented by their confidence in their own abilities, and also by mental resistance to complex and difficult situations of the entrusted missions. Values that reflect the expectations and requirements necessary for forces engaged in the execution of missions and achievement of objectives include patriotism, attitudes towards democracy, work ethics, freedom, honesty, honour, responsibility, heroism, cooperation, and modesty.

Military moral values encompass a wide spectrum of situations and behaviours, extending beyond specific cases to the totality of specific military activities. As for norms and rules, they are seen as models or prototypes of moral behaviour developed within the military system. They have a more focused scope and are applicable to specific situations. By internalising the demands of these values, soldiers manifest their moral attitude through tangible deeds and actions, thus giving life to the ideal and creating standards of behaviour in the form of learnt and embraced actions, from developing courage, the power to face fear, harm, and loss of human life to the ability to strengthen confidence in one’s own abilities.

Professional ethical norms in military morale are prime examples in this regard. The impact of a norm depends on its embodiment in the attitudes and behaviours of military personnel, or at least in the majority of them. Without this practical realisation, a norm lacks normative power to guide individual conduct. The literature emphasises a dichotomy between institutional and occupational aspects, distinguishing between professional service members and military professionals. Charles Moskos’ sociology outlines the unique axiological orientation of the institution, which differs from civil society, and contrasts it with the rational calculation of the market, similar to civil structures. This institutional versus occupational distinction affects mission performance, motivation, and military professionalism. The first dimension highlights the unique responsibilities of the armed forces, from national defence, the risk of life to the oversight of the nuclear arsenal. Here, military motivation is intrinsic, predominantly value-based. The second dimension, occupationalism, sets the boundaries of tasks and stages of mission accomplishment, emphasising performance and extrinsic motivation (financial incentives), thus reducing military functions to monetary aspects and detaching decisions from the military profession. Cross-national studies applying this framework have been conducted in countries such as Australia, Canada, Germany, France, Great Britain, and Greece. Moskos (2005, p. 21) summarised this work in the book, The Army—More Than Just a Job. These studies explore the profile of the military from both institutional and occupational perspectives. Key areas of focus include military professionalism, motivation, and mission performance, highlighting Army morale.

In this research, the morale of the military represents a dimension that denotes, on the one hand, its resistance to extreme situations, being the sum of subjective tendencies and options, manifested by obtaining a positive and optimistic attitude towards overcoming difficulties, and, on the other hand, the totality of external behaviour or mental manifestations that lead to adaptive results through understanding the meaning of the mission, attachment to the combat unit based on the integration of the organisation’s values and beliefs.

In general, human activity is determined by the action of the environment, but it also affects the environment, producing changes in objective external conditions. The specificity of human activity consists in the fact that it has a consciousness of purpose, it is deeply motivated, it operates with tools created by man, and it is perfectible and creative. Through the actions taken on the battlefield, the army produces, first of all, changes in external conditions, in its own internal states and in the relationship with the environment. Second, the army fulfils its mission, satisfies its aspirations, and builds new plans. Third, the army adapts to internal and external conditions. The morale of the military is, therefore, a mechanism that acts with an objective force generated by values, norms, and rules created by the system, and a subjective force, built by a series of states of necessity that demand to be satisfied and push, incite, and lead the staff to their satisfaction, forming the sphere of motivation. Essential to motivation is that it instigates, drives, and triggers action, and this action, through the reverse connection, influences the very motivational basis and its dynamics.

Through this study, our primary objective is to determine whether morale can support military resilience on the battlefield, and if so, then to identify potential improvements to enhance this aspect. The concept of “morale” arose with the recognition of the need for motivation and support beyond the material realm. General Hârjeu (1905, p. 117) emphasised that “physical, intellectual and moral education, conducted harmoniously, constitutes the goal of human education.” Goruneanu (1910, p. 10) also supported the importance of developing the mental faculties and the military spirit, stating the following:

If we were only to study the psychology of the Russo-Japanese war, it would still not be enough to clearly see the capital importance of the development of the soul, faculties and the military spirit in order to had an assured existence.

If the distinction between the importance of morale and other issues is debatable, so is the comparison between the functions of a human being and those of military equipment or techniques in achieving victory. Does this pillar of the conflict require special attention in the conduct of war?

The main elements that support the morale of the military in the conditions of engagement in a mission are the development of moral consciousness and the promotion of moral conduct. Moral conduct, as a crucial aspect of behaviour, involves human actions that are mentally guided and regulated by moral consciousness. This process seamlessly integrates mental and behavioural aspects. Just as moral conduct is a key indicator of a person’s moral worth, moral consciousness reflects one’s moral culture, marking the transition from subjective moral understanding to tangible moral actions. This shift from consciousness to conduct is central to the mechanism. The most important goal of this process is to cultivate the capacity for moral action, which goes beyond mere skills and habits. It involves a transition from automatic moral behaviour to rational behaviour capable of self-renunciation. Such actions represent the highest level of moral conduct because they require robust character traits based on complete freedom from fear and selfishness. The army’s resistance mechanism in a mission therefore involves discipline and following orders, secrecy of actions, emotional control, responsibility, energy, and motivation for engaging in combat actions.

Throughout time, war has emphasised the necessity and importance of certain personality traits in those who lead and engage in it. Traits, such as courage, discipline, self-control, and patience, are inherent in fighters and are often immediately activated in combat -situations. Military specialists identify three essential components for achieving fighter status: technical–tactical training, physical training, and psychological training (Marineanu, et al., 2015, p. 36). Moelker et al. (2015, p. 28) notes that almost all military organisations currently provide some level of psychosocial support to military personnel and families before and after deployment, as they face various challenges and stressors in fulfilling the dual role of the military in their family and life in the army.

There is a known presence of stressors in armed conflict resulting from the participation of military personnel in conflict zones or theatres of operations. However, the scientific evidence regarding the impact of these stressors on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in military personnel is not comprehensive. Significant differences were observed between service members’ subjective perception of the intensity of a combat stressor and its actual potential to cause symptoms after experiencing or witnessing life-threatening events that involved fear, helplessness, and horror (Kokun et al., 2020). Battlefield deployment is only one of many sources of trauma for military personnel that can lead to mental health disorders, including dissociation and, in some cases, suicide (Dwyer and Gbla, 2022, p. 147).

Morale therefore significantly affects the risk of physical and mental health challenges, such as depression and suicide (Bomyea et al., 2012). Research and studies on military families can provide important evidence to support policy and programme decisions so that the military can effectively ensure that families are prepared to meet the challenges they may face. Hawkins et al. (2018, p. 157) believe that families generally function well, but mental health issues and limited communication can compromise family cohesion and individual family members’ preparation, for example, “during the reintegration programme, it can be difficult for families to adjust to the return of a family member, especially if he suffered an injury on the battlefield.” The importance of communication between military personnel and their families, particularly the role of emerging technology, is the subject of Carter’s (2015, pp. 2309–2332) study. It aims to highlight not only the benefits of improved communication but also demonstrate that restrictions on communication and the potential for it to distract service members from their mission also appear to be important factors in the overall dynamics of their military experience. Families often occupy a place of imbalance and have been seen by military institutions as both obstacle and important support mechanism.

For the military to effectively execute missions and follow instructions while contending with various external or internal factors, it must selectively process stimuli. Not all stimuli are necessary; some can be disorienting and lead to serious consequences. This is where the role of anti-redundancy devices becomes crucial, refined through both initial military training and mission-specific training. This refinement allows thought to penetrate causality, enabling the selection and prioritisation of inner motives and impulses and the setting of goals.

Studies confirm that military personnel exposed to the battlefield are at higher risk of PTSD (Hines et al., 2014). Sipos et al. (2014) found that personnel who reported greater battlefield exposure and intentional threat avoidance also exhibited higher levels of PTSD. Predicting human behaviour under extreme conditions and assessing the likelihood of maintaining physical and mental health has always been a scientific concern. Armed conflicts, as extreme and challenging situations, highlight this problem. A key aspect of war is ensuring the physical and psychological security of military personnel and their adaptation to the stressful conditions of war (Prykhodko et al., 2020). All these studies confirm the crucial importance of combat training military personnel before, during, and after their combat experiences.

This study emphasises the significant role of military morale in two areas: its influence on the internal resources of the army during the entire combat process and the support provided by external resources. In this context, the participation of military personnel in the operations carried out by mixed subunits of allied states is a mission with a clear and rigorously defined objective. However, simply understanding and accepting this goal is insufficient for its effective and successful execution. The absence of adequate stimulation and motivational support can lead to mission failure, even if the military possesses well-developed intellectual tools.

Therefore, the accomplishment of a mission requires not only the precise definition of objectives and the provision of the necessary tools but also the invocation of factors that stimulate, raise awareness, and activate personnel. Collectively, these elements constitute the sphere of motivation, which differently sensitises military personnel to external influences, affecting their permeability to these influences. This variation explains, why the same external factor can have different impacts on different individuals or on the same person at different times.

In exploring the phenomenon of war, it is essential to emphasise the crucial influence of psychology on the attitudes and behaviour of combatants. General Marshall claims that “psychology is not just a cultural supplement, but an authentic and indispensable combat weapon” (Popescu-Neveanu, 1970, p. 51).

Thus, the psychological construction of the individual, developed in interaction with the environment, becomes a crucial factor in adapting to the challenges and stresses of war. Soul qualities, such as courage and resistance to fatigue and privation, become essential components for harnessing the internal resources of the army during the battle (Georgescu, 1907, pp. 57, 65). In an environment characterised by danger, uncertainty, and intense physical exertion, morale sustained by these soul qualities becomes a crucial pillar for the success of military operations.

Methods

The study analyses the role of morale in the management of stress during wartime or on a battlefield mission to identify perceptions and representations regarding the importance of morale in a military environment and to identify possible solutions for improvement of the morale of soldiers deployed on the battlefield. We hypothesise that increased morale on the battlefield positively influences the level of engagement of military personnel in war missions or on the battlefield. Psychological preparation and confidence-building must be an integral part of both basic and specialised training, which the military uniquely benefits from. Their development and maintenance are crucial to overcoming the challenges of armed conflict and contribute to army morale. This applies internally on the battlefield, involving interactions with peers and superiors, as well as externally, through engagement with other entities or states. Although its importance is widely recognised, our hypothesis starts from the premise that psychological preparation and self-confidence, as part of basic and specialised training, can represent a specific strength only for human beings and are worth exploiting and maintaining to overcome a conflict armed both internally on the battlefield and by peers and superiors, and externally by other entities or states.

Our methodology delineates the independent variable (army morale support) and the dependant variable (the level of engagement of military personnel on the battlefield). This study takes a mixed-methods approach, integrating both qualitative and quantitative methodologies to examine the role and impact of psychological training and morale in military settings, while the quantitative aspect includes certain questions, such as demographics and experiences in the military. These were statistically analysed to derive percentages and distributions, providing a measurable overview of sample characteristics.

The interview protocol included introductory, transition, and concluding questions systematically designed to address the research hypothesis. These questions were developed based on a comprehensive literature review and aimed to elicit detailed personal experiences and perceptions related to military training and battlefield experiences, as presented in the Appendix. Sampling was conducted in a multinational exercise, and because we did not have a complete list of participants, we performed non-probability sampling on all of them. This approach was chosen because we aimed to capture a diverse range of experiences.

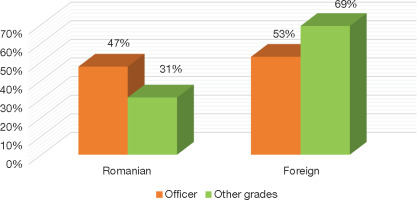

The participants included thirty-two service personnel, all males, of which thirteen were Romanians and nineteen of different nationalities (seven Poles, nine Italians, and three French), all male. Their ranks ranged from officers (nine Romanians, five Poles, two Italians, and three French) to non-commissioned officers (four Romanians, two Poles and seven Italians), aged 29–41 years, all with previous mission experience in conflict zones. The selection criteria focused on diverse experiences in different operational contexts. This experimental research, investigating the influence of military morale in increasing combat power, involved interviewing selected individuals based on their direct involvement in conflict zones. These experiences included engaging in firefights, avoiding ambushes under enemy fire, and participating in actions with national contingents and allied state-level mixed units. The nature of participation in armed conflict varies by context. For example, a service member defending his or her country on the front lines experiences conflict differently than one on an allied support mission. The battlefield, as a central focus of the study, highlighted the resilience of the military during combat and its dependence on the efficient use of resources. The most significant risk identified was the threat of death, a reality faced by study respondents. Facing this ultimate challenge requires harnessing all available resources, especially the internal emotional and psychological forces crucial to overcoming daily confrontations in battle. The interviews were conducted in the Smârdan area, as part of a North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) exercise in Romania, between 24 May 2023 and 4 June 2023. The interview, distinct from the survey method, was used to investigate the attitudes, motivation, self-perception, and image of the interviewees.

This approach allowed for an in-depth exploration of these issues, allowing subjects to articulate their personal experiences. The research used a qualitative data collection and interpretation method. In our data analysis, we took a deductive approach, initially creating a list of categories. These included coding values significant to military personnel (such as work life, family life, and children) and coding attitudes, which captured their thought processes and feelings about their colleagues and immediate environment. Beliefs were also codified based on what the military deemed appropriate, correct and necessary, based on their personal knowledge and experiences. This method was selected primarily because of the purpose of the research, which sought to gather not only responses but also the thoughts and personal experiences of subjects with similar backgrounds. They provided detailed information about specific life stages, their roles within their groups, and the impact of their experiences. Second, the method facilitated the reconstruction of lived experiences and contexts, allowing direct observation of the subjects’ actions and verbal responses. The third, more subjective criterion resulted from the author’s experience in teaching, combining empathy with professional listening skills mastered through psychopedagogical training.

Conducted as a field study during Exercise Saber Guardian, this methodology was deemed most appropriate, given the context and available time resources. It allowed the necessary flexibility to elicit specific and spontaneous responses from interviewees who remained focused and undisturbed by external influences, thus ensuring the collection of comprehensive and relevant data for each question. Given the sensitive nature of military experiences, informed consent was obtained from each of the thirty-two subjects, assuring them at the same time that no one but the author would have access to the recording of this discussion and that what they told the author would only be used for the benefit of research.

Results

The analysis included thirty-two subjects, comprising 13 Romanians and 19 different nationalities (7 Poles, 9 Italians and 3 French), all male between 29 and 41 years old. Of these, 19 were officers (9 Romanians, 5 Poles, 2 Italians and 3 French) and 13 non-commissioned officers (4 Romanians, 2 Poles and 7 Italians). Figure 1 shows the distribution of subjects by nationality and rank. Each has participated in international missions. From 2003–2009, they were involved in Operation Iraqi Freedom, and between 2015 and 2021, in missions in Afghanistan, facing asymmetric threats. Many also served in Bosnia-Herzegovina, initially in NATO's Implementation Force (IFOR) and later in Kosovo Force’s (KFOR) Joint Guardian mission.

All subjects had a military profession and a stable family life, although only 15% had no children. Their backgrounds typically involved stricter parents, middle-class families, and rural upbringings. Key to their personal history was their joining the military and the guiding values of that endeavour. Daily life balanced work and personal interests, such as family or hobbies.

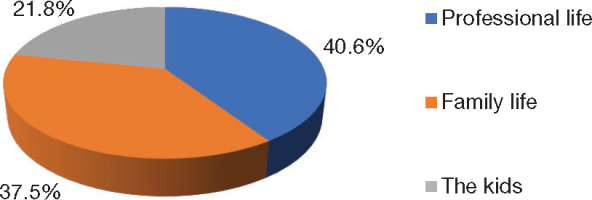

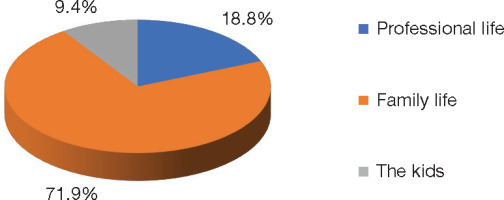

This interview-based study captured particular elements of experiences in conflictual and complex environments. It explored the subjects’ background, material and spiritual conditions, and the interplay between work and family life. Occupational history provides information about subjects’ current conditions and potential stressors. The elements that define satisfaction, along with those that counteract it, show a picture of personal life, revealing the balance between professional and personal priorities. This understanding also sheds light on the circumstances that may act as stressors or catalysts in the lives of the military personnel interviewed. Figure 2 shows that 59.37% of the subjects prioritise family life and children. They find satisfaction in things such as quality time spent together, perceived safety at home, overcoming challenges related to changes in living conditions, stress at work, their children’s schooling, and family health issues. Family is the centre of their lives, providing values that bring balance. A similar proportion of subjects value their work life highly. Notably, among them, nine officers, trained in the military from an early age and skilled beyond the basic hierarchical requirements, became not only fighters but also military leaders, placing professional life first in their lives. Those who are satisfied with their professional or family aspects have shaped their lives around the values, principles, and ideals they live by.

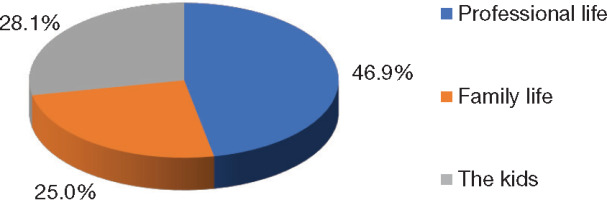

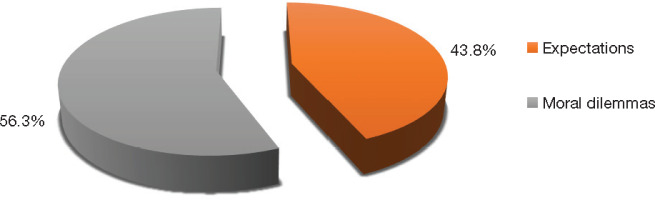

At the opposite end, subjects dissatisfied with certain aspects usually found their work life satisfying but were dissatisfied with family matters and vice versa. As shown in Figure 3, the impact of mission participation on subjects confirmed both subjective and objective effects. Their decision to pursue a military career was influenced by various expectations. Some were influenced by narratives from friends, media portrayals, or film depictions, while others saw the military as a safe lifestyle that matched their capacities and coping mechanisms. A number of them were drawn to the inherent qualities of the military, such as loyalty, integrity, courage, discipline, physical endurance, initiative, and adaptability. Expectations ranged from basic subsistence benefits to loftier goals, such as being part of an elite organisation or contributing to global change. As these expectations evolved, some participants focused more on professional development, leading to dissatisfaction with family life, while others prioritised personal and family aspects, feeling unfulfilled as a result.

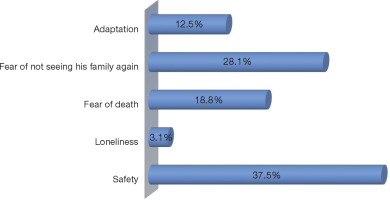

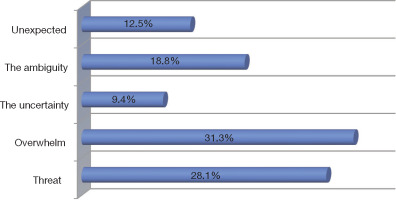

Starting from the fact that the subjects chose to participate in the mission, the study shed light on the understanding of the meaning of military activity in their lives. They acted based on moral reasons, internalised through interactions with society and the military environment. This internalisation shaped the moral individuality and character of each subject, aligning itself with the demands of the military environment. However, this did not prevent them from facing difficult challenges, which gave them opportunities to face a different reality and overcome personal limitations. Among the most difficult experiences, as highlighted in Figure 4, were the lack of safety in combat situations, including firefights, traffic accidents, and explosions. The interviews also revealed other significant challenges: fear of not seeing their families again, fear of death, and adjustment issues, such as lack of privacy, sexual abstinence, maintaining hygiene, and maintaining contact with family only through electronic devices. Loneliness was another difficulty some of the subjects struggled with.

The difficult elements faced by the subjects in critical situations included the fear of death, the anxiety caused by family insecurity, the challenge of adapting to life in foreign and unstable environments, and the disappointment of potential failure or futile efforts. These fears were shaped by their experiences, forming a complex pattern of parallelism marked by thematic and psychological similarities. Figure 5 captures primary fears that include the immediate threat of being shot during combat, the emotional impact of a comrade’s death, and the uncertainty of operating a mission with incomplete information, which involved multiple risks. Ambiguity, characterised by unclear rules in specific situations, and the dread of receiving bad news from home, also emerged as significant fears.

The mission’s impact on the military primarily affected family and personal life, in terms of both connecting with loved ones and reintegration. In their personal lives, mood disorders and depression were prevalent; many felt overwhelmed by situations that were previously manageable, experienced changes in eating and sleeping routines, and poor hygiene. Professionally, some subjects reported reduced concentration and, to a lesser extent, memory issues, although these impacts were less pronounced than in personal life. Re-establishing relationships with their children proved to be challenging, necessitating a gradual approach. All these elements are highlighted in Figure 6.

Returning from a mission often led to a revaluation of the guiding value system, restoring a perspective that highlighted the need for reassessment in light of the lived experiences. This new environment, both different and familiar, challenged some in their reintegration process. However, support of the family environment and an awareness of personal and systemic values added a positive dimension to their mission experience. It also underscored that a well-structured personal profile positively impacts military life. Professionally, this experience enriched their profile by combining intellectual knowledge with moral values. The challenges faced by service members, according to Figure 7, were primarily linked to personal expectations (such as responsibility, self-control, and tolerance) and demands of the military organisation (including discipline, obedience, availability, and resilience) as well as moral dilemmas.

Regarding post-mission support, it was observed that non-Romanian subjects confirmed receiving counselling, a less widespread and articulated practice among Romanians, despite its availability. Only 21.87% of the subjects recognised the need and accessed such support, while the remaining 78.12% did not feel the need for and did not seek professional help. Participating in missions highlighted the challenges they face both during and after deployment. The subjects have demonstrated their competence and professionalism in the field, acknowledging that their training, assessment, and selection for these assignments have significantly improved their adaptability, mental and physical resilience, ability to manage stress, and communication skills. However, Romanian military personnel expressed their concern that the initial training of the military is insufficient, lacking the practical framework necessary for such experiences. Despite this, career progression and additional training provided opportunities to improve and acquire the skills necessary for conflict situations, although they recognised that nothing fully replicated the realities of actual combat. Regarding emotional elements that could improve military training, prioritisation of initial selection and fulfilment of personality criteria were considered important for the development of traits essential for military service, distinguishing them significantly from those in civilian life.

From the perspective of human performance, combat capability and action capability are important in the theatre of military operations. The military system prioritises training and educating troops to develop these capabilities. Key aspects of combat capacity include adaptation, effectiveness, and the management of fatigue and emotional exhaustion. Addressing the latter through training and developing specific skills can be very effective. The ability to perform under stress involves dynamically adapting to different conditions and risks, which are both assumed and motivated. It is obvious that psychological training and morale strengthening are essential in the processes of learning, training, and education, adapted to each specific weapon and speciality.

Maintaining a positive emotional state, essential for a constructive approach and psychological resilience, relies on individual and group contributions, systemic factors, and the domestic environment as well as specific circumstances and support from allied states.

Supporting military families by meeting their needs is a crucial, if seemingly superficial, aspect of sustaining any military involved in a large-scale armed conflict. As Iorga (1994, p. 145) states: “With strong souls the world holds on and moves forward. Nothing is done without them, and with them everything is possible. The battles are not fought with the arm, but with the moral energy that raises it and strikes it.” This moral energy, vital in challenging situations, contributes to victory and must be nurtured. Apparently, beliefs as a distinct part of the army's personality, bridge thought and action and compel individuals to commit themselves fully to their cause. Without convictions, life loses its deep meaning, is reduced to a biological dimension, and blasphemy, boredom, routine, and scepticism begin to surface. The belief that their loved ones are safe from the horrors of war motivates military personnel to fight for victory and fulfil their patriotic and ethical duties. War inevitably leads to either survival or destruction. While survival skills are crucial, the will to survive is paramount. Service members in survival situations face mental stress that can turn even the most of the well-trained individuals into the ones with compromised survivability. Among the many difficulties faced by soldiers and their families, “separation due to operational deployment is the most important cause of stress for military families, which is generated by significant changes in daily routine, additional caregiving responsibilities, absence of emotional support, and fears of loss or injury to the displaced family member” (Dwyer and Gbla, 2022, p. 147). Mental health difficulties can appear long before action on the battlefield, especially in young military personnel who have experienced childhood adversity. Impact research in this area exposes the importance of the role of childhood trauma in association with combat trauma and substance, drug, and smoking use in the context of military battlefield exposure. The finding that stressors (which underlie any type of trauma) “affect military personnel, whether it's morale, psychological state, or substance use behaviour” increases the emphasis on screening for multiple types of trauma before enrolment as well as on early intervention to prevent disaster (Vest et al., 2018, p. 459).

Therefore, a key element in such critical situations is the mental attitude of the military personnel involved. Their firm belief in the safety and well-being of their families is fundamental to their motivation to win the war and reunite with their families. Challenges related to any conflict and deployment of the military on the battlefield were “the inability to communicate with family, the lack of communication, and the inability to care for families both physically and emotionally” (Dwyer and Gbla, 2022, p. 152). A study using data from armed conflicts in Colombia, which looked at the effects of different types of violence and the causes of mental health in its survivors, concluded that, in general, “armed conflicts are associated with a range of mental health problems” (Restrepo and Padilla-Medina, 2023, p. 213). The influence of military service on family life in the Spanish armed forces highlights the relationship between family life and work life through the interactions between the two environments with psychological, social, and institutional factors, where the positive centre of gravity is assimilated to work life, as opposed to family life, at the opposite pole, with negative influences (Escarda et al., 2020, pp. 374–388). The theoretical and practical implications of the military family–work relationship were examined in terms of strategic boundary management in another study of South Korean Navy personnel. It emphasises how trauma and combat experiences affect soldiers’ decisions about their military careers (Choi, 2018, pp. 567–582).

Conclusions

The study highlighted two primary dimensions of analysis: the first one in the form of immediate intervention, from the internal environment of the military during missions, and the second one as external interventions, such as the support of other entities or states, which confirm the influence of the morale of armed forces in supporting the power of the fight. Regarding the first dimension, the psychological demands identified through data analysis were found to come from various sources: danger of enemy fire, presence on the battlefield, concerns about the near future and family, feelings of loneliness, and helplessness, often generating psychological reactions, such as fear, indifference, apathy, and a general sense of low morale. How the effects of these factors can be combated or mitigated helps measure the effectiveness of combat mission accomplishment. These factors were often accompanied by psychological reactions, including fear, indifference, apathy, and a general sense of low morale. How the effects of these factors can be combated or mitigated helps to measure the effectiveness of combat mission accomplishment. Regarding the second dimension, concern and support for military families is another essential factor in building military resilience on the battlefield. This dimension of the analysis highlighted that external support and solidarity with families played a significant role in maintaining troop morale and commitment. Information regarding the status of families and financial and emotional support provided by governmental or non-governmental institutions and organisations were considered crucial aspects in determining the ability to concentrate and determination of the military in carrying out combat tasks. Thus, external interventions and support from other entities helped to strengthen moral resilience and maintain cohesion within the armed forces.

Correlating with other relevant dimensions of military training, such as intellectual, professional, aesthetic, and physical training, influencing morale is not only crucial in initial training but also forms the foundation of a comprehensive pedagogical system. In the current global and specifically Romanian context, the significance of morale is confirmed for achieving victory on the battlefield and the fighting capacity of the armed forces. The practical nature of military activities manifests itself as an expression of individual aspirations, attitudes, and values. It also represents a response to dynamic needs, triggering actions that actively shape behaviour. The tendency of individuals to prioritise certain aspects of their lives helps overcome barriers and difficulties encountered in both personal and professional spheres. This is achieved through action, control, and the provision of qualities of the will (determination, perseverance, etc.). Strong and profound convictions push military personnel to action. Belief in the importance of family life, providing balance and satisfaction, guides their choices and priorities. Similarly, work beliefs motivate them to overcome challenges and shape their behaviour. The value placed on aspects of their personal lives supports their professional endeavours, with the professional ideal evolving into a central and morally significant force in their lives.

This study aimed to assess the significance of morale in military operations, focusing on its dual action capability. Internally, this involves the military's own system of values, beliefs, and needs, which support mental and physical endurance on the battlefield. Externally, it looks at the support systems, such as NATO’s and European Union’s (EU) assistance and humanitarian aid for allied states, which ensure the safety, security, and well-being of military personnel and their families. The research findings emphasise the interdependence of work and family life in the military, highlighting family life as central to morale. The study concludes that mitigating families’ exposure to danger, insecurity, and uncertainty significantly enhances soldiers' combat capability. In addition, it is noted that Romania, along with other European states, contributes to this moral strength by supporting personnel on the battlefield. Finally, the importance of regulatory processes in the conduct of war is emphasised, particularly for soldiers who prioritise their professional commitments based on motivation, will, skills, and activities performed during missions in conflict situations.

To enhance this approach, the study focuses on confidence-related measures, as evidenced by the applied method, for combat stress management. These measures include belief in the legitimacy of the cause and the justice of the war, group integration, beliefs, convictions, hopes, motivation to fight, and moral incentives. These elements form the voluntary regulation that guides military actions and activities. The interplay between voluntary effort and individual values favours behaviour aligned with personal goals. Beyond military training in the sense of acquiring knowledge, training skills, and developing capabilities, battlefield experiences force soldiers to make complex and urgent decisions, relying on qualities, such as quick thinking, self-reliance, courage, experience, and willingness to overcome challenges. The combination of values, norms, rules, and personal traits acquired through training and life experience shapes the military’s behavioural tendencies and choices. Success encompasses not only surviving a hostile environment but also returning to family life and achieving professional victories by pushing the limits in combat situations.

Bearing in mind the principle that military personnel will act in wartime as trained in peacetime, we propose the following for methods of training and education:

At the individual–combatant–military level:

In war, on the battlefield, the service member is the main link, surpassing the importance of equipment and devices. Therefore, the selection and orientation of military professionals is crucial in psychological training.

General and specialist military training in environments similar to the realities of the battlefield is essential for the mastery of weapons and combat techniques in solving tactical situations.

Improving the motivational system is a key to accurately assessing, accepting, and assuming risks, including potential injury or death.

Development of both mental and physical dimensions prepares staff for prolonged effort and cultivates self-confidence.

These approaches collectively contribute to the formation of a member/combatant/individual capable and fully strong for battlefield conditions.

At the group–collective–subunit level:

Integration into the group significantly stimulates combative behaviour, cultivating military order, discipline, team expertise, solidarity, and a strong unity for the successful completion of the mission.

Creating strong informal interpersonal relationships is essential for effective group integration.

At manager–leader–commander level:

The readiness of the subunit for combat depends on the professional skills of the commander, character, personal example, and attention to subordinates.

The commander is an essential figure of trust, responsible for using the motivational system and focusing on educating the concepts, attitudes, and behaviours of military morale.

Emotional intensity can destabilise staff behaviour, especially in new or unusual situations. Extreme emotions, such as anger, sadness, or fear can prevent effective performance and make the individual aggressive and helpless, thus becoming an obstacle to the effective performance of the activity. The military, as a collective system, forms group opinions and attitudes through member interactions, establishing norms of behaviour to achieve goals. Being in a group fosters consensus and solidarity, providing a support system in difficult situations. When difficult situations have a negative impact on military personnel, the group serves as a key asset in restoring balance and providing moral support to the affected ones. Therefore, in complex scenarios, military support initially comes from within the group or system itself, with external intervention following as appropriate.

Although it is a flexible research method that produces quick results and honest and spontaneous responses, the interview as a research approach has also generated limitations, such as some potential biases and the inability to generalise results as well as the inconvenience of subjects having response regardless of their mental state or state of fatigue. Although the interview provides a framework for free expression of opinion, some subjects may feel pressured to respond in a socially acceptable manner or according to institutional expectations, which may have affected the sincerity of their responses. Also, the dependence on the subjects’ answers could have limited the coverage of important aspects, invisible to their subjectivity or topics that they did not perceive or did not want to reveal. Support for military personnel in armed conflicts extends beyond the group to include external military and civilian contributions. Supporting military families is crucial for moral support. Our research can contribute to a better understanding of the types of institutional deployment support that would be pertinent to the needs of soldiers on the battlefield. The future directions for action may include identifying recruitment methods that highlight various trauma or addiction issues, a careful review of military training means and methods, and also developing an analysis of the importance of resilience training to support capacity building the army to deal with very stressful situations without reaching the stage of developing dysfunctional reactions and behaviours.

Other future lines of action could involve researching and implementing specific strategies to improve morale among military personnel, given the various challenges and pressures they face during and after deployment. Special attention could also be given to the development of emotional and psychological support programmes aimed at strengthening the moral resistance of the military and facilitating their adaptation to conflict situations. In addition, periodic assessments of morale within the armed forces could provide useful information for the ongoing adjustment of military personnel management policies and practices.

Regarding the second dimension, in relation to external interventions by other entities or states, the solidarity of states in various aspects—economic, material, moral, civil protection, and child protection—is extremely important. Messages of support from the international community, including the EU, play an important role in maintaining the morale of the warring population as well as the armed forces. This moral dimension of external support contributes to strengthening their resilience in the face of challenges and maintaining faith in the justice and importance of their cause. Thus, moral support not only supports morale but also strengthens determination and resolve in the struggle for fundamental values.