Introduction

Within the context of Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine, increasing geopolitical turbulence, and hybrid threats, Latvia, as an external border country in North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), has to be a vigilant guard of both its own and NATO’s defence priorities. A comprehensive defence framework was established in 2019 in Latvia with aims to implement a whole-of-society approach, meaning that everyone, including the private sector, clearly sees the part it has to play in the defence framework and contributes to it. At the 2016 Warsaw Summit, NATO (2023) recognised that the strategic environment had changed and committed to accelerating resilience “to the full spectrum of threats” by defining seven baseline requirements for national resilience against which the level of preparedness of members could be measured. This commitment demonstrated that the “resilience of civil structures, resources and services is the first line of defence for today’s modern societies” (Roepke and Thankey, 2019). According to NATO, strengthening resilience is primarily a national responsibility and individual states can do this by developing their own national defence capacity.

With strategic communication being an integral part of NATO’s efforts to achieve political and military objectives and within the context of developing a resilience communication framework, the purpose of this research is to explore the role of the private sector within Latvia’s high-level strategic defence documents, focusing on dimensions of psychological resilience and strategic communication.

The involvement of the private sector is regularly debated from the perspective of very practical angles—cooperation in the fields of critical infrastructure, cybersecurity, development of military industry, and disaster management. There are very few examples when dimensions of psychological resilience and strategic communication are analysed from the private sector perspective.

The relevance of the research topic is based on three main arguments. Firstly, the increasingly complex security environment requires everyone’s involvement. As stated in the Comprehensive National Defence System in Latvia, the threat level to Latvia has reached such a complex level that the protection of the country with military means alone is no longer sufficient because it does not cover all aspects of hybrid threats. The national defence of Latvia must be comprehensive and must be based on the readiness of the entire society and state institutions to overcome the crisis, resilience against external influences as well as on the ability to resist and renew after challenges and crises. For this purpose, the national defence system must be adjusted so that it is based on mutual trust and partnership between citizens and state institutions as well as on the responsible attitude of the whole of society towards the state and its security (Government of Latvia, 2019).

Secondly, public trust in the state administration and official institutions is low. About one-third of the Latvian population does not trust any of the most important Latvian institutions (Providus Centre for Public Policy, 2021). The 2022–2023 winter Eurobarometer survey data on Latvia indicates that trust levels in Latvia are relatively low—the majority of Latvians do not trust the Parliament of Latvia (61%) or the government (61%), 78% do not trust political parties (European Union, 2023). The national security concept highlights that the internal security environment is negatively impacted by society’s low trust in the state administration and political parties. As the population’s alienation from the state increases, society’s engagement in everyday social and political activities decreases as well as its ability to mobilise in situations critical for state defence (Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Latvia, 2019).

Thirdly, the potential of the private sector to break the cycle of mistrust and contribute to the implementation of national security and defence priorities is an in-depth topic worth putting on the agenda. According to the Edelman Trust Barometer, business is the only trusted institution that is seen as competent and ethical, and society wants more societal engagement from business. In comparison, the media, government, and NGOs have experienced a significant decrease in public trust over the past few years (Edelman, 2023). This can be seen as a window of opportunity both on a country level and in the international environment. More debate and research are necessary regarding the involvement of the private sector and its contribution to broader societal dimensions, including those related to national interests and defence.

Consideration of the above-mentioned three arguments together with a framework of comprehensive defence is where the significance of this study arises. The expectation is that everyone is involved in achieving the priorities of national defence and security, including private individuals, NGOs, and other stakeholders. But in order to progress in this direction, a clear path of strategic setting needs to be put in place and an institutionalisation pattern on how to implement the ambition practically must exist.

Three research questions defined for the study are as follows:

How have theoretical concepts of psychological resilience and strategic communication evolved, and how are they explained within the comprehensive defence framework?

How has the role of the private sector evolved within the main strategic defence documents of Latvia over time, and what are the main differences among various defence dimensions regarding cooperation, responsibilities, and ties with the private sector?

How much is the private sector involved in the dimensions of psychological resilience and strategic communication in Latvia’s strategic defence documents and what directions can be identified for further collaboration?

In the existing literature, two main thematic lines can be identified—the literature either focuses on tying together psychological resilience and/or strategic communication with national security issues from the perspective of public institutions alone or focuses on institutional changes to private sector entities and their impact on society. This research addresses the gap and provides an interdisciplinary view, combining the private sector with national defence interests within the dimensions of psychological resilience and strategic communication.

The structure of the paper is as follows: Firstly, the comprehensive defence framework is reviewed as a basis for the research topic. The next sections focus on the evolution of key concepts (psychological resilience and strategic communication) in the theoretical literature. This is followed by a discussion about the relationship between the strategic communication of the private sector and the enhancement of psychological resilience and an empirical study of Latvia’s strategic defence documents that allows us to draw the first conclusions on the theoretical underlying factors.

The comprehensive defence framework and the role of the private sector in the face of hybrid threats

The concept of comprehensive national defence is a highly dynamic one and is being adapted to the evolving security challenges through the addition of new elements that are essential for national defence (Berzina, 2020, p. 12). Scholars distinguish comprehensive national defence as a form of modern-day total defence, noting that hybrid threats in the 21st century have contributed to the rebirth of the concept. Comprehensive national defence thus integrates both military and non-military means. Berzina (2020, pp. 7–8) identifies two basic principles governing comprehensive national defence—the whole-of-society and whole-of-government approaches.

Finland, Sweden, Australia, Singapore, and Switzerland are among the countries that are often analysed within the context of successful implementation of a comprehensive defence framework. In 2019, the Cabinet of Ministers of Latvia approved the implementation of the Comprehensive National Defence System of Latvia. The central narrative of the Comprehensive National Defence System of Latvia highlights the responsible attitude of all Latvian citizens towards the country and its security.

The main goal of the system is to promote citizens’ readiness to defend the country, to create pre-conditions for overcoming crisis, and to ensure the operation of important functions for the country during crisis and other upheavals. The operation of nationally important functions is ensured by creating a planning, coordination, and partnership system among state institutions, the private sector, NGOs, and citizens (Government of Latvia, 2019).

The need for comprehensive defence is often viewed within the context of an ever-growing bunch of hybrid threats, highlighting that hybrid threats cannot be addressed by military and traditional security providers alone. This is where other parties, such as NGOs, private sector actors, and society, in general come in. As hybrid threats can refer to very diverse dimensions within societal structure, a defence framework needs to be established on a comprehensive approach and built as a joint action of stakeholders, including civil society and the private sector (Cederberg and Eronen, 2015, p. 6). Similarly, among measures to counter hybrid operations, public–private cooperation is paramount as “most critical functions of European society these days are operated and managed by private sector actors” (Wigell, Mikkola and Juntunen, 2021, p. 18).

In the Comprehensive National Defence System framework of Latvia, it is emphasised that “hybrid war has become an extension of the foreign policy of some countries in order to achieve favourable conditions for their national interests abroad using non--military means” (Government of Latvia, 2019). It means that to effectively embed the comprehensive defence system and address hybrid threats, the strategic involvement of all parties is required. According to Latvia’s strategic defence documents, everyone has an important role in strengthening national security and defence. Responsibility must be taken at the level of individuals, organisations, private sector, and state institutions, and this is especially significant in times when security challenges are becoming more complex and spread across various networks and channels.

The resilience concept and psychological resilience as an objective part of comprehensive defence

The rise of the concept of resilience marks a fundamental shift from the old logic of security associated with the Cold War and indicates broader socioeconomic changes brought about by the historical transition from liberalism to neoliberalism. If insecurity is seen as the starting point of governance, then resilience can be seen as a “business move” that encourages entrepreneurs, communities, and individuals to manage their own risks—”subjects that are able to take care of their own security are less of a threat to themselves and thus also not a threat for the governance capabilities of their countries and the global order” (Brasset, Croft and Vaughan-Williams, 2013, p. 224).

In the context of resilience policy, scholars talk about the shift from state to nodal security governance, meaning that the state is acting only as one node within a network of nodes participating in the delivery of security (Button, 2008, p. 15). At the same time, this does not mean that the power of state or classical operators of security policy has diminished—”the various new nodes of security governance are defined as locations of knowledge, capacity, and resources that can be deployed to both authorise and provide governance” (Button, 2008, p. 15). According to NATO, countries where the whole of government as well as both public and private sectors are involved in civil preparedness planning have fewer vulnerabilities (Roepke and Thankey, 2019).

“Technological and societal complexity of the so-called ‘risk society’ indicates challenging times for traditional top-down models of security governance, leadership, and management, both within and between sovereign entities,” and resilience-based approaches have the potential to reverse the top-down leadership process (Juntunen and Virta, 2020, p. 75). The concept of resilience aims to increase the capability of individuals and communities to be able to act independently and not to rely on authorities excessively, meaning that security is enabled in various societal junctions, including organic leadership and grassroots levels. Such thinking acknowledges that traditional governance models based on linear development of events are not sufficient (Juntunen and Virta, 2020, p. 75).

Comprehensive defence and resilience concepts are often associated with long-term effort and results. It is a significant narrative to stick with, especially when thinking about purposeful efforts in dimensions of psychological resilience and strategic communication. Resilience should be described as a comprehensive process, not only rapid response to crisis and restoring the status quo (Wigell et al., 2021, p. 19). The typical model of comprehensive societal resilience created by Hyvönen and Juntunen refers to two dimensions—-when responding to crisis resilience is a temporal process, but more broadly it should be perceived as a nested or layered attribute that cuts through society (Wigell et al., 2021, p. 4). In this context, the term “social resilience” is used as well to illustrate the resilience on a group level that emphasises the community aspect and highlights that the whole is more than some of its parts. The resilience of the community as a whole can be high despite the existence of non-resilient individuals and less-resilient moments (Gal, 2014, p. 454). This means that it is necessary to address resilience through a long-term lens and via an overarching resilience umbrella that can add value for society as a whole.

To dive deeper in unpacking what exactly constitutes the resilience of society in the long term, scholars highlight that social resilience on a national level is contingent upon individuals’ well-being, a sense of patriotism, and trust in the state leadership (Gal, 2014, p. 454). Kimhi and Eshel (2019, p. 526) employed two studies validating a National Resilience Scale of thirteen items to measure national resilience, and the results in one study constituted a national resilience of three factors: identification with my country, solidarity and social justice, and trust in public institutions. The other study suggests a component of patriotism, optimism, and trust in national leadership. Many of these aspects are highighted among the important ones in the national-level definitions of psychological resilience in Latvia’s strategic defence documents. The National Defence Concept of Latvia defines various fields where long-term efforts need to be taken in order to ensure the basis for the resilience of society—public education of society, resistance to manipulation, practical readiness to overcome crises, and civic engagement (Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Latvia, 2020). There are the following nine focus areas defined in the Comprehensive National Defence System of Latvia: development of military capabilities and improvement of defence strategies; promotion of cooperation between the private and public sectors in the field of defence; teaching the basics of statehood in Latvian schools and public education; civil defence; psychological defence; strategic communication; economic resilience; the strengthening of law enforcement and security institutions and cyber security (Government of Latvia, 2019).

As to the term “psychological resilience,” many definitions describe it as having common characteristics that include the ability to withstand some form of traumatic stress or adversity. Some definitions refer to adaptive adjustment resulting in a return to baseline levels of functioning, while others emphasise positive growth and flourishing beyond the baseline (Meredith et al., 2011, p. 2). In Finland, where the comprehensive defence approach is among the most developed in the world, the term “spiritual” was initially used in local language when refering to psychological defence, thus indicating a much broader ideological and societal agenda (Hyvönen and Juntunen, 2020, p. 162). The Comprehensive Defence System of Latvia defines psychological resilience as a set of purposeful and planned measures for the protection of society against internal and external conscious and unconscious negative influences and society’s will to protect the strengthening of the state (Government of Latvia, 2019).

Analysing lessons from international approaches in this context, Caves et al. (2021, p. 10) highlight that the psychological preparedness of a society or country is often seen as a key element in the context of resilience, but it is difficult to measure objectively. The researchers highlight that the ability of the defence industry to promote physical resilience is clear, but its contribution and impact in promoting national psychological resilience is unclear and less directly visible, given the lack of objective measurements. Psychological resilience requires more attention. It is related to the morale of the civil society, its will to defend its country or to do voluntary work in other ways, and the resilience of the society against disinformation and propaganda (Christie and Berzina, 2022). To sum up, the resilience is defined as a crucial concept within the comprehensive defence framework and it is accepted that new actors, including the private sector, NGOs, and others enter the field and inherit power and responsibility to enhance resilience. Psychological resilience is seen more as a sub-category of overall resilience, and in definitions it often overlaps with general characteristics of the resilience concept whilst at the same time maintaining the central core related to patriotism, identification own country, and a trust in the country and its institutions.

The basis of strategic communication and the involvement of third parties

To describe a concept that includes complex and comprehensive communication processes, channels and tools used to achieve objectives of national importance in the field of defence and security, Vince Vitto, US Department of Defense Science Board Chairman, in 2001, first used the concept of “strategic communication” (Defense Science Board [DSB] Task Force, 2001). Strategic communication plays an important role in national and international, diplomatic, economic, security, and defence relations. It is both the process and the tools by which organisational goals are achieved. It derives from the organisation’s strategic plan and, in the case of countries, from strategically determined national interests and focuses on the role of communication in the implementation of the organisation’s strategic goals (Mitrovic, 2019, p. 43).

One of the challenges faced by the strategic communication concept is the different approaches defining it. Although there is an agreement on the core of the concept, strategic communication details mean different things to different people (Paul, 2011, p. 2). Strategic communication scholar, Christopher Paul (2011, p. 4), however, points to the following four central elements that define the core of strategic communication: (a) informing, influencing, and persuading are essential; (b) effective informing, influencing, and persuading demand clear goals; (c) coordination and avoiding conflicting information is necessary to avoid adverse effects; and (d) actions are communication.

Strategic communication has a central role in the NATO Alliance as all aspects of NATO have a critical information and communications component. In 2009, NATO approved an overarching political–military strategic communications policy, where strategic communication (StratCom) is defined as coordinated and appropriate use of NATO communications activities and -capabilities – Public Diplomacy, Public Affairs (PA), Military Public Affairs, Information Operations (InfoOps), and Psychological Operations (PSYOPS), as appropriate – in support of Alliance policies, operations and activities, and in order to advance NATO’s aims (StratCom–NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, 2009, p. 1).

The key principles of StratCom are consistency of message, active engagement in the information environment (including social media), accuracy and clarity, effectiveness (clearly defined, measured, and reviewed), multiplicity of efforts and maximum reach (engaging all NATO communications capabilities and all available communication platforms to strengthen the dissemination of consistent messages), and soliciting public views and adapting efforts as necessary (StratCom–NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, 2009, pp. 2–3). In 2019, the Terminology Working Group of the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence defined strategic communications as “a holistic approach to communication based on values and interests that encompasses everything an actor does to achieve objectives in a contested environment” (Bolt and Haiden, 2023, p. 31).

Within the framework of this research topic, public diplomacy and public affairs are especially significant, as the first is about NATO civilian communications and outreach efforts to promote awareness of and building understanding and support for NATO’s policies, operations, and activities, and the latter focuses on NATO civilian engagement through the media to inform the public of NATO policies, operations, and activities in a timely, accurate, responsive, and proactive manner (NATO Strategic Communications Policy, 2009, pp. 1–2). The declaration of the 2009 NATO Strasbourg Summit emphasised that it is increasingly important that the alliance communicates in an appropriate, timely, precise, and responsive manner about its development roles, goals, and missions (StratCom–NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, 2023). Many member nations define strategic communication as a military function, whilst others talk about strategic communication as being part of the national instrument of power—and therefore a cross-government activity (Tatham and Le Page, 2014, p. 2).

Consequently, the question arises as to whether only states can implement StratCom or non-state actors, the private sector, and others can project it as well. Price (2015, p. 7) refers to the growth of StratCom, highlighting that the modern arsenal of StratCom-ready capabilities maintained by states, corporations, religious institutions, and non-governmental organisations are “heavily subsidised, usually transnational, engineered”—and thus can potentially devastate traditional ideas of community realisation and self--determination. With great power comes great responsibility and as the modern information space is levelling the playing field, “the idea of a shift from state to non-state actors as dominant proponents of strategic communications is accepted with little qualification” (Bolt et al., 2023, p. 17. Scholars highlight that over the course of debates, a societal security and defence dimension, seemingly inherent in strategic communications, has taken shape (Bolt et al., 2023, p. 17).

The Comprehensive Defence System of Latvia defines strategic communication as a strategic action aimed at achieving the strategic goals of the state (or a specific institution) and is interpreted in the context of these, and when implementing every initiative, the impact of strategic communication on society and on a specific audience is purposefully planned and managed (Government of Latvia, 2019). The focus of strategic communication should not be the government narrative but the national one—it should reflect the national interests and goals articulated and defined by the nation. A national narrative should be based on an understanding of how people in a given country give meaning to their world; it should identify society’s priorities (Cornish, Lindley-French and Yorke, 2011, p. 23). With reference to theoretical literature, the NATO–StratCom approach and how it is implemented, it can be concluded that nowadays StratCom capablities are part of its arsenal and ready to be used by third parties as well. This stance is widely accepted and can employ broad dissemination of messages based on the values of society, giving a meaning that conveys centrally supported messages in the same way as done by official authorities.

Synchronising the theoretical concepts analysed in the previous two sections with the framework of the Comprehensive National Defence System of Latvia, the characteristics of the dimensions of psychological resilience and strategic communication can be defined as follows (Table 1).

Table 1

Characteristics of psychological resilience and strategic communication

Similar pillars have been defined as central for the comprehensive national defence framework of Estonia as well, and instead of “psychological resilience” it is referred to as “psychological defence.” Both dimensions are seen as complementing fields “dealing with the societal fabric and communicative realm” (Juurvee and Arold, 2021, p. 83).

The private sector as contributor to defence goals–enhancing psychological resilience via strategic communication

In order to put the role of the private sector in a more detailed context, it is significant to elaborate on ties between strategic communication and psychological resilience. When discussing the strengthening of resilience, many scholars address the importance of communicative aspects. According to Anderson and Guo (2021, p. 23), resilience is an ongoing sense-making process that relies on communicative interactions, including those that occur between stakeholders and organisations. Buzzanell (2010, p. 1) argues that resilience is not a trait that someone possesses, but rather an ongoing activity that is made meaningful through communicative processes—resilience is “developed, sustained, and grown through discourse, interaction, and material considerations.”

Taylor (2011, p. 436) theorises about rhetoric and the public relations of organisations as essential to building and sustaining society and contributing to the creation of social capital. Additionally, in the field of communication studies, the term “resilience communication” is often present. Recently, there has been a shift regarding this field as scholars began to research how communication is constituted in and constitutive of resilience – Buzzanell (2010, p. 9) focuses on communicative construction of resilience identifiying five processes involved in fostering resilience. This shift led to the development of resilience communication, which refers to the discursive practices that encourage resilience at multiple levels (e.g. individual, organisational, community, and national levels) (Buzzanell and Houston, 2018, p. 2). In conceptualisations of community, resilience communication is the central component of most if not all community resilience models, but theorising about community resilience and communication via mutual interaction has been absent (Houston et al., 2015, pp. 271–272).

It is evident from the work of scholars that in reslience strengthening, strategic communication is seen as a vital aspect and when used purposefully, it can contribute to broader goals of enhancing psychological resilience. In 2020, Finland launched a broad strategic communication campaign, where one of the main objectives was to strentghen psychological resilience through communication. The campaign was decentralised and used the government’s power to onboard various groups from the civil sector, business, and academia, around seventy in total, thus enabling the main messages to reach diverse communities. Campaign products were diverse—government-created content, YouTube videos promoting mental health, volunteer stories, and others. Campaign results significantly improved the overall social cohesion and trust indicators in Finland’s institutions. According to NATO–StratCom conclusions, communication campaigns that have a basis in long-term cross-government policy can unify actions across departments. This allows communication campaigns to focus on their chosen topic while still contributing towards a larger mutually supportive goal. In this instance, the psychological resilience security functions (Hassain, 2022, pp. 13–16).

Cornish et al. (2011, p. 23) emphasise the importance of third parties, stating that if strategic communication in all its forms is a tool for the implementation of the national strategy, then not only the political and military leadership have to be involved in this process, but in a more subtle way non-governmental organisations, the private sector and others as well, who could act either consciously or otherwise in the space of the national strategy and in the interests of the state (Cornish etal., 2011, p. 23).

The private sector can play an important role in strategic communication, especially in the conflict stabilisation and transformation dimensions. It can bring a different skill set to the field and help to depoliticise and demilitarise strategic communications by operating outside of government messages. Media campaigns, creative strategies, and other external activities implemented by the private sector can have a place in the design and implementation of a national strategy to enhance efforts and facilitate greater engagement with a wider audience (Cornish et al., 2011, pp. 23–24).

Methods

Strategic defence documents define a country’s priorities at the highest level and are the starting point for agenda setting and the involvement of different parties. To study the role of the private sector and its evolution within the strategic defence documents of Latvia, an in-depth analysis of defence sector strategic documents was carried out.

The National Security Concept and the National Defence Concept are two backbone documents that define the strategic framework for the national defence of Latvia. The National Security Concept is prepared by the Cabinet of Ministers, while the National Defence Concept is prepared by the Ministry of Defence. Both documents are approved by the parliament of Latvia at least once in each convocation and both are prepared on the basis of an analysis of national threats. The National Security Concept defines basic strategic principles and priorities for the prevention of national threats that must be taken into account when developing new policy planning documents, legislation, and action plans in the field of national security (Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Latvia, 2019). The National Defence Concept defines basic strategic principles, priorities, and measures of the nation’s military defence in times of peace, national threats, and war (Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Latvia, 2020).

Quantitative content analysis and qualitative text analysis were used to analyse National Security Concepts and National Defence Concepts in the period from the restoration of Latvia’s independence up to today. Quantitative content analysis was used to find out the frequency and intensity of private sector mentions, making it possible to objectively and systematically describe the visibility of the private sector. Qualitative content analysis was used to evaluate the context of the mentions and level of activity attributed to the private sector.

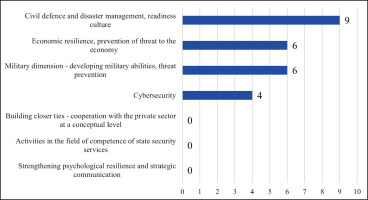

Fourteen strategic defence sector documents were analysed in total—seven National Security Concepts and seven National Defence Concepts. In order to conceptualise the role and involvement of the private sector, the following seven content analysis categories were developed inductively based on overarching categories of the National Defence Concept:

Building closer ties—cooperation with the private sector at a conceptual level

Cybersecurity

Economic resilience, prevention of threats to the economy

Activities in the field of competence of state security services

Strengthening psychological resilience and strategic communication

Military dimension—developing military abilities, threat prevention

Civil defence and disaster management, readiness culture

The role of the private sector within strategic defence documents was analysed using defined keywords and context: the total number of mentions, dynamics over time, direction of activity or cooperation as well as the type of wording of the mention itself—whether it is neutral or defined as an activity to be carried out by the private sector or the state.

Defined keywords for the content analysis of strategic defence documents: “company,” “private,” “merchant,” “partner,” “organisation,” and “commerce” (in original documents key words in Latvian were analysed: “uzņēm,” “privāt,” “komersant,” “partner,” “organizāc,” and “komerc”). The analysis includes mentions where the private sector is identified as a separate actor (i.e. mentions with the meaning “companies as individual actors or a third party to which specific content is attributed” and not, for example, the business environment in general).

Results

Role and evolution of the private sector in Latvia’s strategic defence sector documents

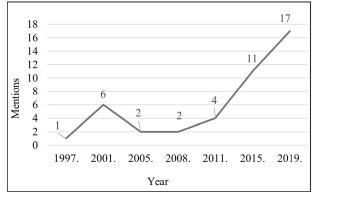

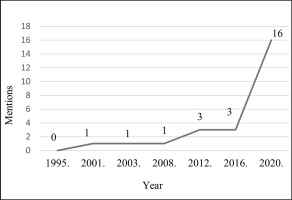

For the time period from the beginning of 1990 up to today, fourteen strategic defence documents were analysed. In total, the private sector as a separate actor is mentioned for sixty-eight times in these documents—forty-three times in the National Security Concept and twenty-five times in the National Defence Concept. The role of the private sector in strategic documents has grown significantly in recent years and the highest number of mentions was identified in the two latest documents approved in 2019 and 2020—-seventeen mentions in the National Security Concept and sixteen mentions in the National Defence Concept, respectively (Figures 1 and 2).

Mentions of the private sector within strategic documents are mostly formulated in a neutral way, without a specific attribution or expected action from the private sector or the state—out of sixty-eight mentions, fifty-one are neutral. Twelve mentions define the need for state to act or commit to take further steps—for example, the responsible institutions need to provide support to entrepreneurs in promoting exports, strengthen cooperation on cybersecurity issues, and the government needs to contribute to promote the cooperation of large foreign entrepreneurs with companies in Latvia. With regard to the private sector, the expected activity from entrepreneurs is identified in five mentions—mostly related to issues of critical infrastructure and civil defence, for example, “the basic functions of the company must be ensured in case of crisis and war, continuing to ensure the functioning of the national economy, the production of necessary goods and the provision of services” (Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Latvia, 2020).

Economic resilience and cyber security—the clearest vision of partnering with the private sector

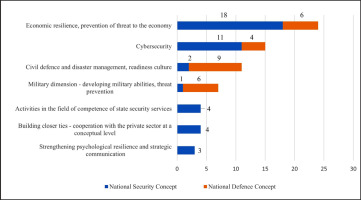

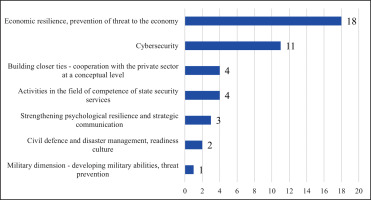

In total, in both documents, the private sector is mentioned the most (twenty-four mentions) in the category “Economic resilience, prevention of threat to the economy,” where issues concerning increase in the competitiveness and productivity of companies, the risks of an unstable economic environment, and the support in promoting exports and acquiring new export markets are addressed (Figure 3).

In the context of cybersecurity issues, the private sector is also mentioned quite often (fifteen mentions) and with relatively precisely attributed commitments and the involvement of the state. It is repeatedly emphasised that “cooperation with the private sector needs to be strengthened, ensuring mutual understanding and contribution towards strengthening the overall national cyber security and threat prevention” (Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Latvia, 2019). The insufficient understanding of the involved parties as to how to strengthen cyber security and direct investments to this area is also highlighted as well as the need for joint cybersecurity training courses. At the same time, it is also emphasised that it is necessary to think about increasing benefits for private critical infrastructure actors, from whom additional obligations and responsibilities are required.

There are certain differences between the private sector mentions in the two strategic documents. Unlike the National Security Concept, where the main focus is on economic resilience and prevention of threats to the economy (eighteen mentions), the private sector is most often mentioned in the category of civil defence and disaster management (nine mentions) in the National Defence Concept, where it is seen as an essential part of the civil defence system (Figures 4 and 5).

In the National Defence Concept, the emphasis is on the importance of cooperation with private sector companies that contribute to guaranteeing critical infrastructure as well as on the need to create a culture of readiness. In the National Defence Concept, the connection of the private sector with the military field stands out more clearly (six mentions)—for example, cooperation with the private sector in the field of anti-mobility, involvement in military exercises, and inviting companies to strengthen national defence by encouraging employees to participate in the National Guard and the National Armed Forces Reserve are mentioned.

Psychological resilience and strategic communication—almost left out for the time being

In fourteen defence sector strategic documents that were analysed, the dimensions of psychological resilience and strategic communication were mentioned thrice in connection with the private sector. All mentions were in the National Security Concept; no such mentions are identified in the National Defence Concept since 1995.

Aspects of psychological resilience and strategic communication were mentioned for the first time in the National Security Concept of 2015, when the general need for cooperation was defined. The concept states that “in order to achieve greater public involvement, it is important to ensure targeted strategic communication between the highest officials of the country, society as a whole, as well as its individual groups, for example, entrepreneurs and representatives of the non-governmental sector” (Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Latvia, 2015).

After 2015, two mentions within this context were identified in the National Security Concept of 2019. Firstly, the need for the government’s strategic communication with various groups, including regional entrepreneurs, was outlined. Secondly, the need for the private sector to play an active role in the context of disinformation is defined, stating that “the priority interest of Latvia in the EU is to ensure that the private sector also effectively counters disinformation. Greater accountability and transparency must be achieved from IT companies and online platforms” (Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Latvia, 2019).

Discussion and conclusions

Since the restoration of Latvia’s independence in 1991, the role of the private sector in the strategic documents of Latvia’s defence sector has grown significantly. In the first strategic documents, the private sector as a separate actor or partner did not appear at all or appeared for few times, but the trend in recent years has been going upwards. Over time, diversity of cooperation dimensions has increased as well, and the private sector is increasingly seen as an equal and important partner whose involvement can help to achieve the goals of national defence and national security more successfully. The role and involvement of the private sector in the latest strategic documents is discussed in several areas essential to national security—cyber security, promotion of economic resilience, civil defence, and readiness culture.

In both National Security Concept and National Defence Concept, the private sector is mostly mentioned in the context of cooperation on very practical matters—supply chains, critical infrastructure, and strengthening cybersecurity. The role and involvement of the private sector in strengthening the psychological resilience and strategic communication has been examined very little. The most recent defence sector strategic documents do not identify the role of the private sector in these two dimensions as essential or as the one that needs to be developed in the future. In these dimensions, the focus is on more active performance from the state institutions; the private sector is viewed as a recipient of information, rather than an active actor that could contribute to these dimensions.

At the same time, among high-level priorities to prevent threats to the information space, the need to develop the country’s strategic communication capabailities is highlighted in the National Security Concept. It is emphasised that “strategic messages of Latvia, based on the unifying values of the society defined in the Constitution, must be developed and consistently used in communication. [...] The sense of belonging to the country and the understanding of democratic and historical values of the population must be further promoted” (Ministry of Defence of the Republic of Latvia, 2019). This illustrates that at the national level, there seems to be a clear understanding and ambition to improve this area, but as for now without engaging the private sector as there are almost no indications that point to the private sector within these dimensions.

Analysing NATO–StratCom capabilities and theoretical literature on strategic communication and psychological resilience, several directions for more active involvement of the private sector can be identified. Among them are public diplomacy and public affairs performed by the private sector that can be implemented successfully also outside the scope of organised and centrally driven state narratives. Private sector companies implement various communication activities on a daily basis (campaigns, social projects, intitiatives to enhance individual involvement, etc.) that can directly contribute to overall psychological resilience—improve individual identification with the country, accelerate social trust and trust in public institutions, instensify state narrative on success stories, and genarate patriotism.

In order to effectively contribute to the delivery of NATO–StratCom, the ability to coordinate NATO and coalition information and communications activities with the efforts of other agencies and partners within the context of a broader NATO strategy is defined (StratCom–NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, 2010, p. 5). In 2020, NATO reached out to civil society, youth, and the private sector for their input on NATO 2030 in order to strengthen the alliance. Several dialogues were organised to address the evolution of private sector engagement. Regarding the information landscape, it was pointed out that the private sector, including small and medium enterprises, has access to extensive data that can help inform public sector responses to threats in the information space. The importance of wider public outreach to promote media literacy was stressed as well (NATO, 2021).

At the same time, many scholars emphasise the problem of fragmentation on the government side as the reason why it is difficult to implement a coherent strategic communication approach—when there are many institutions that are resposible for different fields, it is challenging to create a picture for the country as a whole. According to Sweden’s example, for psychological defence to be effective, it must be strategic and in order to succeed, it has to have a special, central status within the total defence framework, otherwise the risk is to lose it among various government agencies. “It should have a clearly civil status in order to guarantee it an autonomous role” (Swedish Defence Research Agency, 2017, pp. 3–4). In practice, formulation of policies regarding involvement of the private sector and civil society is still very much a top-down exercise, and resilience is used “more as a pedagogical framework to inform the public on the official doctrinal purpose and functions of the comprehensive security model” (Hyvönen and Juntunen, 2020, p. 167).

This study highlights many directions in which future research needs to be targeted to get a more comprehensive understanding of the private sector role within national defence strategies. The separate research focus has to be on overall environments in national countries towards engaging the private sector, including what the establishment is, the degree of instutionalisation, and historical development. Motives to involve or not to involve the private sector in these two dimensions can be studied in depth as well—from the perspective of state, regulatory framework, and development of society (values and sense of belonging). The comprehensive defence framework is a separate overarching topic for focused research—how it is implemented in various countries, what are the differences, what factors determine whether this framework stays in strategies only, or whether it has already entered a serious implementation phase for diverse actors, including the private sector. Additionally, more clarity is needed regarding defining the dimensions of psychological resilience and strategic communication, as it is seen from theoretical concepts that these dimensions often overlap and it is worth questioning whether they need to be separated or analysed as complementary. Referring to Estonian strategy documents, Juurvee and Arold (2021, p. 87) similarly note that the distinction between two disciplines—-psychological defence and strategic communication—seems artificial, and executing them in parallel lacks rationale. The authors argue that principles of strategic communication could be an extension of non-securitised areas of policy planning.

To conclude, in today’s technologically advanced and networked society, actions from state and official institutions are not enough to shape public opinion, drive engagement, and create a sense of belonging. The activities and involvement of other actors can be equally significant—third parties, including the private sector, can promote or weaken the achievement of policy goals, public education, and formation of opinions on topics relevant to the country. The dimensions of psychological resilience and strategic communication therefore have the potential to be used for the smart involvement of the private sector, but significant further research is needed to get a more comprehensive idea of both the theoretical grounds and empirical evidence.

Limitations of the study: As this study focuses on the research of strategic defence documents alone, the level of abstraction limits the in-depth discussion on the involvement of the private sector. This research is considered as the first step that provides one reference point regarding this complex and multi-layered topic.