Introduction

The influence of identity on the dynamics of security and politics is inevitably crucial. Realism as an approach has been long abandoned by many political science scholars; the overemphasis on states to what is perceived as ahistorical is the common argument against the paradigm. Despite criticism, I believe that there is potential in refining realism to better fit the complexities of today’s political landscape. This involves highlighting its ability to analyse power dynamics in modern hybrid political contexts. Realism theories from classical realism, neorealism, defensive realism, and offensive realism require contemporary perspectives, particularly given the current political landscape characterised by technological advancements and the overlooking of identity establishment concepts in assessing power dynamics.

This paper introduces techno-realism as a continuation of the development of realism subsequent to offensive realism. It posits technology as the primary means of power in contemporary politics, while concurrently acknowledging the significance of identity formation in political contexts. Furthermore, it explores how technology facilitates the circulation of power, not only among states but also among non-state actors that wield considerable influence in contemporary political landscapes.

The traditional understanding of warfare, commonly linked to combatants, has become obsolete. Contemporary challenges, from the progression of weaponry and its destructive capabilities, as well as the surreptitious extraction of data from civilians, have the potential to be weaponised against them. The initial case study of this research focuses on the Uyghur minority issue in Xinjiang. This issue has evolved into a digitally driven method of control, demonstrated by extensive surveillance and various cyber measures being implemented by the Chinese government in the region. This is also facilitated by the participation of various technological industries, the emergence of new technologies, and the implementation of cyber measures by the Chinese government to restrict the freedoms of the Uyghurs and the Xinjiang region.

In the international realm, concerns over China’s technological advancements in the Indo-Pacific region have brought to light the concept of “digital authoritarianism,” exploring how technology is utilised by authoritarian regimes for surveillance and repression. Meanwhile, Indonesia, a significant middle power in the region, demonstrates similar technological influence, notably exhibited during its 2024 elections, serving as another case study in this theoretical paper. The central inquiry of this paper delves into the potential evolution of political realism by redefining the central interests variable to encompass technological advancement.

It poses the fundamental question: To what extent does technology serve as a means of power acquisition for states, and how do identity formation processes become foundational elements within political agendas that use technology, considering the involvement of other significant actors beyond states?

The aim of this paper is to introduce a new theory within the realism school of thought that can be applied to analyse contemporary political issues by examining the -interplay between technology and political power dynamics. The paper aims to enhance our -comprehension of the changing landscape of global governance and statecraft in the -digital age.

Theoretical Framework

The Need for Techno-Realism in Contemporary Political Science

The realism school of thought has been criticised for its inclination to heavily prioritise states, often overlooking the importance of domestic politics. I argue that instead of outrightly rejecting or directly opposing realism, it should be modified or adjusted to rectify its shortcomings. Adopting the ideological emphasis of classical realism and incorporating the notion of human nature without discarding the neorealist concept of external systems that define how actors act, techno-realism aims to find a middle ground. Techno-realism introduces a few key concepts: identity establishment, technological advancement as a means of power, and the role of non-state actors in interconnected relations, to be used in the analysis of contemporary warfare. It explores the role of non-state actors, including big-techs, while affirming the significance of states as central elements in power struggles.

Unlike concepts, such as anarchy, balance of power, and hegemony (Diez et al., 2011), techno-realism operates as a theory. It is the continuation of structural realism, classical realism, defensive realism, and offensive realism (Lobell, 2017) within the paradigm of political realism, offering a more contemporary approach to understanding the role of technology in politics, especially amid contemporary challenges, such as hybrid wars and repression.

Historically, in 1998, Stephen M. Walt delineated three major approaches in political science: realism, which gained prominence during the Cold War, focusing on domestic politics and its impact on states; liberalism, which emphasises interdependence as a pathway to peace; and constructivism, which offers a distinct analysis of identities shaped by historical processes. This poses the question of how constructivism may be more applicable as a theory than realism, as it acknowledges non-state actors and constructing beliefs behind politics. However, according to Palan (2000), constructivism borrows an outlook from social theory that is often deemed counter-intuitive and fallacious, leading to its classification as a not well-defined sociological approach.

In the context of technology in politics, Joseph Nye, a prominent neoliberalist figure, has acknowledged the significance of technology, specifically cyberspace, albeit not as a central focus. Nye (2010) argues that the imbalances in accessibility, anonymity, and vulnerability in cyberspace empower smaller actors, thereby enhancing their capacity for both hard and soft power and challenging established global norms. While acknowledging technological advancement as a potential re-shaper of power dynamics among states, Nye’s (2010) -analysis lacked a conceptual framework for analysing adversaries, particularly in distinguishing motives and identifying actors in cyberspace. A compelling example is the blurred line between cyberterrorism and hacktivism, highlighting the need for techno--realism as a theory for analysing the foundational identity establishment of power struggles within cyberspace.

The need for a new theoretical perspective stems from the shortcomings observed in existing frameworks. Structural realism, for instance, while dismissing notions of human nature and the ideological aspects of “humanist realist” (classical realism), overlooks power struggles within domestic politics that can extend to international affairs. Neoliberalism acknowledges the importance of technology for states but lacks a versatile conceptual approach to address contemporary issues comprehensively. Meanwhile, constructivism, while presenting an “alternative,” grapples with the complexities of balancing states’ interests and cooperation, thus encountering challenges in delivering a holistic analysis of the behaviour of states.

Identity Establishment: Fundamentals of Power Struggle in National Interests

The first assumption of techno-realism is that in analysing both national and international politics, national interests are highly interrelated to political ideology implemented at home. That being said, the projection of national interests in the international realm is an extensive form of what is happening at the domestic level and vice versa. Building on Morgenthau’s analysis of domestic politics and political ideology in his work Politics among Nations, political ideologies manifest as a contest for power (Bliddal et al., 2013). Morgenthau argues that ideologies serve as a “language of power,” shaping national morale and reflecting states’ stances on morality and justice, which ultimately benefits the state. A state’s failure to project such values weakens its international position, with ideologies neatly categorised into three boxes: status quo, imperialism, and ambiguity (Morgenthau, 1948, pp. 61–69).

In contrast to Morgenthau’s three boxes of ideologies, techno-realism contends that national interests are the direct byproducts of ideologies and crucial for power struggles, rooted in realism’s core concept of human nature. This underscores the significance of examining political ideologies in both domestic and international political analyses, recognising the hierarchical nature of domestic politics and the prevailing anarchy in the international arena. Such recognition is in line with the acknowledgment that human nature influences objective laws, highlighting the imperative of pursuing national interests wherein political ideology serves as a fundamental component. The realist tradition, drawing from Machiavelli’s perspective on egoistic passions and the potential for cruelty (Donnelly, 2000, pp. 19–23), grounds its understanding of human nature. Techno-realism embraces this idea, exploring how our fundamental human nature shapes political identity and ideology, ultimately dictating the direction of interests.

On technology, Morgenthau in 1951 argued that the total war at that time had fundamentally altered the traditional relationship between political ends and military means, and had instead become a universal destruction equipped by modern technology which also transformed policy into reductio ad absurdum (Nobel, 1995, pp. 61–85). Exploring human nature-related philosophical inquiries through the lens of techno-realism involves addressing fundamental questions, such as the following: How does human nature shape power structures? Does the need of repression imply that authoritarian states are more efficient than their counterparts? If fear plays a dominant role, can political identity, religious beliefs, and ideology offer viable alternatives in structuring politics? Moreover, which organisational structure—anarchy or hierarchy—better accommodates intrinsic human nature? To what extent is the concept of a “wicked” human nature supported by contemporary science?

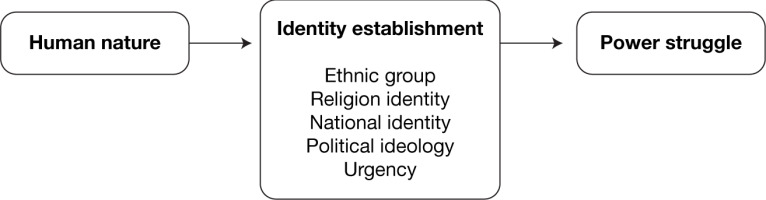

In response to these inquiries, techno-realism operates using a structured approach: rooted in human nature, political entities establish identities encompassing ethnic groups, religious beliefs, national identity, political ideology, and urgency, thus engendering power struggles among these identities.

Techno-realism bases its power struggle analysis on the fundamental concept of human nature, echoing Machiavelli, the realist tradition, and evolutionary biology. In a joint research in 2004 entitled “Machiavellian Intelligence as a Basis for the Evolution of Cooperative Disposition,” the study highlights the interconnectedness of Machiavellian intelligence and cooperative behaviour in shaping how humans coexist and engage in social interactions. It suggests that cooperative dispositions, akin to the tit-for-tat interaction and the prisoner’s dilemma, don’t necessarily require genetic relatedness but individuals encountering each other repeatedly (Orbell et al., 2004).

Gilpin’s (1984, pp. 287–304) piece defending the realism school of thoughts from Richard Ashley’s critics examines three main shared assumptions of realism: the first is the conflictual nature of international politics, the second is the notion that Homo sapiens is a tribal species who are loyal to the tribe which are now associated to nation states, and the third is men are ultimately motivated by fear. Along the line of realist tradition in politics, there was also Schmitt (2007), who argues that any opposition, whether rooted in religious, moral, economic, or ethical differences, becomes politically significant when it effectively organises human beings into distinct categories of friends and enemies, with the political essence lying not in the battles themselves but in the behaviour shaped by the ability to discern the real friend and enemy based on a clear evaluation of the concrete situation.

Building on this, techno-realism analyses identity formation, shaped by factors, such as ethnic, religious, national, political, and common urgencies. It aligns closely with the concept of “identity politics,” encompassing a broad spectrum of political activity and theorising rooted in the shared experiences of injustice within specific social groups (Heyes, 2020). Nevertheless, techno-realism is grounded in the classical realist understanding of human nature that is motivated by fear.

The fundament of techno-realism is closer to Freudian ideas on intrinsic impulses and the conflictual instinct of human beings. George Kennan argued that nationalist sentiments originated from a universal human desire to belong to something greater than oneself (Schuett, 2010, pp. 21–46). Slavoj Žižek (2012) argues that the rise of religious or ethnic justified violence these days is due to the fact that one needs a greater, “sacred” reason to use violence. He emphasises that religious ideologists usually claim that religion has helped “bad people to do some good things,” and he then quotes Steven Weinberg’s claim that only religion can make “good people do bad things.” Techno-realism elaborated this claim further—that it is not just religion that has the capability to provide a greater alternative motivation to do something moral or immoral but any form of identity formation as illustrated in Figure 1.

To sum up, techno-realism posits that the development of an identity framework has a significant influence in collective power struggles and interest narrative. Each element mentioned has the potential to either combine or operate independently. For example, political ideology and national identity often concurrently shape national interests in power struggles on national, regional, and global scales.

Technology as the Means of Power

The second assumption of techno-realism is rather straightforward, the fundamental nature of warfare is technologically based, and technology is the means of power. Technological power can be exercised at any given level; from micro level, meso level, and macro level to global level. In realism tradition, John J. Mearsheimer argues that states can be qualified as a great power if they have sufficient military assets that can be deployed in a conventional war scenario. He also argues that there are two kinds of powers that states may possess: latent power (a state’s wealth that includes its technology) and military power, both are interrelated with each other (Mearsheimer, 2003, pp. 5–58). Techno-realism emphasises this notion further and perhaps to its extreme—that technology is not merely a tool for military advancement but a means of power in itself.

Technology no longer has to be geared towards defence and military development to augment state power in domestic and international politics. In today’s landscape, technology spans from cybersecurity and artificial intelligence (AI) surveillance to facial recognition systems, space technologies, command and control systems, and nuclear technology, constituting its own form of warfare. These advancements empower both state and non-state actors, underlining why states, such as Israel and Singapore, are considered great powers.

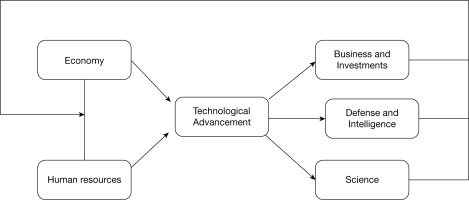

Figure 2 shows how techno-realism analyses technology as the centre of states’ power acquisition. From an economic standpoint, the growth of states is crucial, and a successful economy relies on a skilled workforce. The connection between economic prosperity and skilled human resources is essential, serving as both prerequisite for technological advancement and outcome of power acquisition. Effective governance is a key to achieving a thriving economy, regardless of the economic or political system in place. Human resources or technological literacy rooted in education and skill training play a pivotal role in determining the possibilities achievable through technological progress.

In the realm of technology as a means of power, advancements occur in three spheres: science (space exploration, biotech, AI development, robotics, etc.), defence, and intelligence (advanced weapon systems, unmanned aerial vehicles [UAVs], cybersecurity, AI surveillance, etc.), and business and innovation (investments abroad, semiconductor industry, e-commerce, digitalisation, and Big Tech). These technological advancements generate power, creating a cycle of power struggle in the digital era, with the resulting power translating back to the economic realm. In the era of information revolution, technological advancements in various sectors are integrated into numerous aspects, from business processes to control systems. While these computer-based systems offer growth opportunities for governance, they also increase the risk of cyber attacks with real-world consequences.

Two significant issues arise in the growth of cyberspace: firstly, the internet’s widespread use facilitates the empowerment of non-state actors, leading individuals to shift from traditional identity beliefs to competing identifications based on religious and ethnic affiliations. Secondly, the information revolution alters the relationship between citizens and governments by increasing awareness, as seen in the effects of digital media during events such as the Arab Spring. By adopting network-centric warfare as a framework, states have proven their ability to conduct operations that are more effective. In contemporary ius ad bellum, the issue would be the legalised response of states to attacking non-state actors, which is in practice often accepted by international communities when it is categorised as armed attacks in self-defence (Dinniss, 2012, pp. 13–113).

Recognising Non-State Entities within a State-Focused Framework

One of the most common criticisms of the realist school of thought is that the theories are exceptionally state-centric. When they are applied to some distinct cases, such as terrorism, realism fails to provide a framework for analysing the issues from the vis-à-vis perspectives of both states and non-state actors involved. While acknowledging the validity of the argument that non-governmental organisations (NGOs) possess a non-binding existence and importance, it is crucial to note that in the post-9/11 world, neorealism, grounded in the assumption of an anarchical global system, tends to overlook the increasing significance of non-state actors and their complex identity establishment.

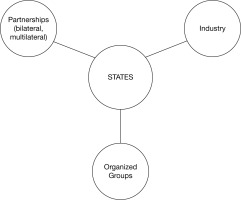

These then emphasise the importance of two things that were not essentially acknowledged by previous thinkers in the realism school of thought; first is the acknowledgment of non-state actors. In the digital age, realism encounters additional challenges, including the rise of organised hacker groups, the rapid growth of the technological industry, and the emergence of bilateral and multilateral collaboration among states. These elements could directly impact states’ national interests and affect national security.

Second, the structure of political realm that has partly evaporated into the world of data and cloud, the cyber realm in itself is a vast space without borders. I argue that it is anarchy in its purest form; from individual actors, such as black hat hackers, hacktivists, or those that are funded and supported by states, to an intelligence alliance, such as “The Five Eyes.”1 Some threats are especially related to extremist organisations, for instance the increased use of virtual currency (VCs) to finance terrorism because of its anonymity. Extremist organisations, such as United Cyber Caliphate and Islamic State (IS), also use cyberspace to widen the influence of their propaganda.

Figure 3 is a model of the actors mapping in contemporary politics according to techno-realism. States, as the core figures, are inherently complex in nature. Within states, there are individuals whom realists refer to as statesmen—decision-makers and political leaders. Each actor has its own interests shaped by its fundamental identity establishment. Partnerships are inevitably vital for states in today’s landscape of security and politics. Realism, in its natural form, is highly sceptical of certain elements labelled as “international,” such as international organisations, international laws, and all non-binding matters that continue the pretence of maintaining peace. However, techno-realism argues that partnerships, or in its original term, alliances, possess a greater degree of power and enforceability. The importance of such partnerships, organised groups as well as the tech industry, determines states’ policies and strategies in achieving their political interests. Hence, techno-realism’s argument on identity establishment is manifested in contemporary policies and strategies that revolve around technological advancements, which are further explored in the approaching sections.

1. First Case Study: China’s Cyberpolitics on Xinjiang

According to techno-realism, when delving into both national and international politics, there’s a strong link between a country’s national interests and the political ideology it practises domestically. Simply put, how a nation expresses its interests globally mirrors what’s happening on the home front and vice versa. China’s global mega project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), makes the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region a pivotal gateway that serves as an essential logistics hub, seamlessly integrating rail, road, and air transportation. The Urumqi International Land Port exemplifies its commitment to expanding trade networks, actively fostering connections with neighbouring countries and facilitating seamless connectivity to Europe through the China–Europe Railway Express, covering 19 lines connecting 26 cities in 21 countries, including regions around Xinjiang and countries in the Caspian Sea, Black Sea, and Russia (China Global Television Network [CGTN], 2021).

Historically, Millward (2004) argues that by the end of the 19th century, the Uyghur nationalist movement had spread through education, industrialisation and trade. China’s significant national interest in Xinjiang also revolves around the strategic importance of the Tarim Basin’s natural gas, exemplified by the China National Petroleum Corporation’s (CNPC) Tarim Oilfield, reporting an annual production of 33.1 million tons in 2022, supporting the nation’s energy security (Global Times, 2022). Another most crucial interest in China’s energy supply security in the region is that Xinjiang has 450 billion tons of coal reserves, which makes the region the fourth largest coal producing region in China (Xinhua, 2022).

To justify political and security measures in the region, the Chinese government attributes escalated incidents of terrorism and violence to entities identified as “East Turkestan” forces. Between 1990 and 2001, over 200 incidents linked to these forces resulted in 162 deaths and more than 440 injuries. Additionally, violent events occurred in 2002, alongside the notable “July 5” riot in Urumqi in 2009 (Consulate General of the People’s Republic of China in Chicago, 2019). Since then, the concern about regional instability and terrorism provides justification for the Chinese government to establish vocational education and training centres in Xinjiang, commonly referred to as re-education camps by the media. According to the Council on Foreign Relations (2019), since 2017, the Chinese government has detained over one million individuals and subjected the remaining population to extensive surveillance, religious constraints, forced labour, and forced sterilisations, which have been identified as potential crimes against humanity in a report by the United Nations and the United States.

In addition to that, authorities in Xinjiang have implemented policies aimed at deradicalisation, incorporating strategies known as the “five keys,” “four prongs,” “three contingents,” “two hands,” and “one rule.” In techno-realism’s analysis of national interests, understanding identity establishment is crucial. In one of China’s key approaches to Xinjiang, it stated: “Ideological problems should be solved by means of ideology” (Zhou, 2017).

Aligned with the framework of techno-realism, China strategically employs identity enforcement measures with the specific aim of suppressing the Uyghur identity. This deliberate strategy is supported by a consistent evocation of the fear of separatism, strategically integrated into the Chinese government’s narrative of “deradicalisation.” China’s policies towards the Uyghurs have consistently been more stringent, compared to those applied to their more assimilated Muslim counterparts. This strict approach was further intensified in 2016 when Chen Quanguo was appointed as the Party Secretary of Xinjiang, a decision made in response to a surge in terrorism that had significantly affected the country, resulting in hundreds of deaths. The Chinese government viewed these activities as the product of Islamic extremism, and hence saw “deradicalisation” as the best strategy with which to address the problem. Many limitations apply to the Xinjiang region and its Uyghur people. The regional disparity becomes evident when viewed through the lens of national identity (Zhang, 2022).

In furthering this deradicalisation measure, the Chinese government also has programmes that focus on three groups: imprisoned radicals, released radicals, and those who haven’t been in prison. These encompass custodial, post-imprisonment, and social programmes (Zhou, 2017). According to the Chinese government, the situation in Xinjiang is deemed necessary as a response to the formidable challenges posed by radicalism, separatism, and extremism, which are perceived as significant threats to China’s national interests. The Chinese government asserts that its efforts to counter separatism and terrorism in Xinjiang are conducted within the bounds of lawfulness and in accordance with the United Nations Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism. The Chinese government also contends that its approach to deradicalisation is centred on aiding individuals influenced by extremist and violent ideologies, with the goal of enhancing their lives by liberating them from harmful beliefs (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, 2019).

In addition to promoting the deradicalisation narrative, the Chinese government also embraces the concept of the “Three Evils” as outlined by the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). Initially founded in the early 1990s to resolve boundary disputes, the SCO has evolved into a platform for security cooperation, particularly in combating terrorism and extremism. The Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS), established in 2003, has played a pivotal role in this endeavour. The SCO strategy encompasses addressing the core security concerns of Central Asian leaders, with a specific focus on combating the “three forces” or “three evils”—terrorism, extremism, and separatism. Effectively addressing these risks is deemed essential for each member state to safeguard their own stability and that of the broader region (Aris, 2009).

Sean Roberts argues that surveillance, indoctrination, and confinement networks are actively erasing the Uyghur identity by disconnecting social ties, discouraging use of the Uyghur language, and dismantling cultural practices seen as a threat by the government. Simultaneously, it strongly enforces compliance with policies promoting Uyghur assimilation and transforming the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) to remove signs of its native culture, except for a sanitised version aimed at tourists. The Uyghur language is disappearing from public spaces, mosques and Muslim graveyards are being destroyed, and traditional Uyghur neighbourhoods are being demolished. Those not interned are pushed to work in the security system or new residential industrial brigades, away from their families (Roberts, 2022, pp. 1–12).

China’s Cyber Measures Against the Uyghurs

Analysing from the principles of political realism, I argue that the term cyberpolitics implies the use of the cyber domain, infrastructures, and tools as a means of power in politics, which is related to the core of techno-realism that emphasises “technology as the means of power.” With China increasingly relying on technological progress, the government began perceiving unrestricted information as a direct threat to the nation and its political system. One of the biggest challenges when examining cyberpolitics is the different definitions of “cyberspace” that some countries adopt. The widely accepted notion of cyber realm’s borderlessness is a subject to debate due to the emergence of cyber sovereignty, exemplified by China’s implementation of the Great Firewall and associated measures. This concern is manifested through the firewall’s monitoring of Internet traffic within Chinese cyberspace, alongside China’s active cooperation with SCO in addressing cybersecurity issues.

To determine China’s definition of cyberspace, I refer to its official statement in a published document by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China in 2021. The Chinese government acknowledges the interconnected nature of cyberspace and physical space, presenting both risks and opportunities, with challenges such as cyberterrorism, attacks, false information, and personal data abuses. China asserts the importance of information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure jurisdiction within its territories, advocating for non-interference in other states’ ICTs, known as cyber sovereignty, while also underscoring the significance of data security, advocating for the protection of personal information and opposing mass surveillance by states through ICT tools (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, 2021). According to this government publication, I would summarise China’s definitions and declaration of its cyberspace as follows:

Cyber sovereignty is a jurisdiction over ICT resources, data, activities, and infrastructure that are being exercised within state territory.

Cyberspace is highly connected to physical assets.

Cyberspace and its risks include unauthorised data collection, cyber attacks, espionage, user manipulation, cyberterrorism, and sabotage.

Mass surveillance is included in cyberspace.

The use of cyber governance should be transparent.

Based on these definitions, it is evident that the manifesto’s implementation in Xinjiang aligns with the concept of Chinese national cyber sovereignty. This suggests that all cyber activities in the region, such as data collection, are regarded as internal affairs and should not be subjected to interference from other states or external entities. While China actively promotes its Digital Silk Road (DSR) initiative beyond its borders, it adopts a stringent stance to safeguard its own cyber sovereignty and territorial integrity.

China has consistently enforced its cybersecurity laws, including the Cybersecurity Law enacted in June 2017, the Regulations on Internet Security Supervision and Inspection introduced in August 2016, and the recently enacted Data Security Law, which took effect in September 2021. In the realm of cyberpolitics, data emerges as the most crucial element, potentially becoming oppressive when personal data exploitation occurs without consent and transparency. I argue that cyberpolitics extends beyond conventional warfare tactics, such as distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, data breaches, phishing, malware, and spoofing, encompassing all aspects related to data and its accessibility. Cyber sovereignty embodies the comprehensive authority of states over their domestic and international cyber affairs.

Technological advancements in cyberpolitics serve as indispensable tools for accruing power and ensuring stability, both crucial for China’s survival and pursuit of its national interests. This is exemplified by China’s justification for cyber radicalisation and institutionalism, as reflected in its cyber measures within its jurisdiction, particularly in Xinjiang. These measures include cyber espionage, censorship, and mass surveillance deployed in the region. It’s essential to recognise that while technology itself is neutral, its application in politics demands ethical and moral scrutiny.

The Chinese government claims that every measure that is taken in handling the issue of terrorism in Xinjiang is in accordance with Article 3 of the PRC’s Counter-Terrorism Law. While the definition of extremism that is in accordance with Paragraph 2, Article 4 of PRC’s Counter-Terrorism Law is “hatred, discrimination and agitation” for violence that becomes the basis of terrorism acts. For the Chinese government, the law itself has no specific religion or race as its subjects, and this applies to any form of movements that are identified as such (Information Office of the People’s Government of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, 2022).

Since the “Strike Hard” campaign took place, some religion-related regulations were established to eliminate extremism that included certain behaviour and activities that were identified through signs and expressions, such as inciting jihad or carrying and advocating terrorism activities. However, these signs are not limited to the use of hijab by women or the “abnormal” length of beards for men even to the usage of virtual private networks (VPNs). These extremism policies also have a direct impact on the implementation of surveillance systems and cyber control over the region. Such a system has been developed by the Chinese government in collaboration with the private sector in enforcing biometric data collection, technology acquisition, facial imagery, iris scans, surveillance cameras, and big data technologies (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights [OHCHR], 2022).

Sarah McKune argues that due to the perceived threat that civil and political rights may pose to China’s stability, certain Tibetan and Uyghur NGOs have become legitimate targets of offensive cyber activities (Lindsay et al., 2015, pp. 261–281).

Oliver Marguelas (2019) argues that following the online dissemination of extremist propaganda by the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, particularly during the Urumqi incidents, the Chinese government imposed strict limitations on digital services and speech for the Uyghurs. These restrictions extend beyond jihadist-related content to include access to religious practices and communities. In the private sector, companies, such as Tencent, reportedly increased their Uyghur-speaking staff by 600 to monitor content. This crackdown has led to a significant increase in the domestic security budget, which exceeded China’s defence spending in 2016, which amounted to US$25.6 billion.

The cornerstone of China’s restriction of cyber freedom is the implementation of the Great Firewall, which is seamlessly integrated into the cyber landscape of Xinjiang. While Facebook and Twitter have been banned nationwide since 2009, Tencent’s WeChat has emerged as a dominant platform for public cyber activities in China. Many individuals have turned to WeChat forums to exchange information on Islam, political events, and cultural issues. Darren Byler (2021), an American anthropologist, contends that the substantial investment in the private sector to develop Chinese infrastructure, including the US$8 billion growth of the security and information technology market in Xinjiang up to 2018, has significantly transformed the landscape of freedom restriction in the region. Many companies have adopted techniques utilised by the US government contractors, such as Palantir, an automated digital analysis tool capable of real-time data analysis on social media. This technology has led to numerous detentions following the detection of suspicious keywords related to extremism and terrorism.

I argue that both espionage and mass surveillance are incorporated as matters that fall within the scope of cyberpolitics, particularly when it is not classified to the public how the government processes the collected data, or when it is used for political agendas or oppression. China’s AI development has also been deployed in its mass surveillance systems. The surveillance system milestone reached in Pingyi County from 2013 to 2016, when more than 28,500 security cameras were installed, which commenced China’s great initiation in a large surveillance network. The system is directly integrated to police monitoring and automated facial recognition algorithms, and the footage is also accessible from mobile phones. The Chinese government then embarked on the Sharp Eyes or “Xueliang Project” journey in enhancing its surveillance systems and installations across China. Currently, China has more than 200 million security cameras installed as part of the ongoing Sharp Eyes projects, such as Safe Cities, SkyNet, Golden Shield Project, and Sharp Eyes (Thompson, 2021).

China is also using its cyber-tech advancement in BigData by creating the well-known social credit system (SCS), which is a real-time data-power project to monitor citizens’ behaviour. SCS was first initiated as a tool in the market reform initiative, and in 2002, transformed to be a part of the Chinese Communist Party in establishing a “unified, open, competitive and orderly modern market system.” This system works as a national incentive mechanism that can identify whether a citizen or business enterprise engages in unlawful and treasonous behaviour and add them to the “blacklist,” and the ones that engage in trust-keeping activities are added to the “red list” (Cho, 2023). Once added to the “blacklist,” the individual is disqualified from buying airplane tickets, banned from buying property, or getting a loan until he or she pays the obligatory fine or bills (Nast, 2019).

From the Chinese government’s perspective, the installation of CCTV cameras is not aimed at any ethnic or religious groups, which is a common practice globally, backed up by the reference that the United Kingdom installed 4.2 million surveillance cameras (Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the State of Kuwait, 2022).

The role of technology industries in this deradicalisation narrative is also crucial. Two major Chinese companies, Hikvision and Dahua, which manufacture the biggest surveillance systems and equipment globally, had been accused of being involved in human rights violations in Xinjiang. Hikvision is a surveillance subsidiary of state-owned Chinese Electronic Technology Group, Tianfu, which has become the leading provider of video surveillance globally. Both Hikvision and Dahua control 60% of the total surveillance equipment market. The use of their technology keeps on expanding, and as per November 2021 report, there were more than six million camera networks facilitated by Hikvision and Dahua in 191 countries outside China (Time, 2023).

In 2022, two cutting-edge spyware apps were discovered in Android apps that were presumed to target the Uyghur population and were able to track the location of users and collect their information. According to the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP, 2022), this spyware was created by Chinese state-sponsored hackers due to its overlapping history with previous cyber activities of its target, for instance if users have been activating a VPN or using applications that have religious content, and such activities can result in detainment in re-education centres.

Exiled Uyghur associations have been subjected to numerous cyber attacks that have been attributed to the Chinese government. In June and July 2011, the World Uyghur Congress (WUC) reported a DDoS attack that was followed by a barrage of calls and emails, rendering their accounts inaccessible for two days. Additionally, in June 2012, Kaspersky Lab found a Trojan attack against Uyghur rights groups that had been employing ZIP files that created backdoors, enabling control from command servers traced back to China (Radio Free Asia, 2012).

Some cyber-related issues are occasionally used to support human rights abuse narratives, and this includes both state-related and commercial actions. In 2019, Google’s Project Zero (2023) discovered a website with thousands of users every week that set up watering hole attacks on its visitors and secretly placed monitoring implant iPhone devices running iOS 10 to iOS 12. This accusation was then used to claim that for the past 2 years, multiple malicious websites have been used to monitor the Uyghurs using iPhone devices. Apple Newsroom (2019) then denied this claim, and particularly that it was related to human rights violations and data privacy of a religious minority group, and quickly responded that the vulnerabilities had been patched in recent versions.

2. Second Case Study: Social Media as an Electoral Tool and a Means of Control in Indonesia’s 2024 Presidential Election

The surge in social media usage in Indonesia is fuelled by the expansion of digital population, driven by heightened Internet accessibility and the affordability of smartphones. As of February 2022, Indonesia boasted approximately 167 million active social media users, ranking third in the Asia Pacific region after China and India, and solidifying its position as the leading social media market in Southeast Asia (Nurhayati-Wolff, 2024). This widespread adoption of social media has profoundly affected political engagement and discourse in Indonesia, particularly among the youth demographic. A notable example is President Joko Widodo’s effective use of these platforms during the 2012 Jakarta gubernatorial election, which coincided with a surge in social media usage and contributed to his national prominence (Nugroho and Wihardja, 2024). This shift in focus towards exerting civilian and electoral control through social media platforms reflects Indonesia’s prioritisation of technological power. While previously, money politics and political banners were the primary means of influencing people’s choices and controlling the population, its significance has diminished in the 2024 election, compared to the power dynamics observed in social media.

Techno-realism suggests that technology functions as a power tool across various sectors, including business, military, and science. In the context of Indonesia’s 2024 presidential elections, this perspective becomes particularly relevant as we observe the pivotal role of technology, especially social media. Here, political buzzers alongside influencers on social media platforms emerge as significant players, shaping public opinion and influencing voter behaviour. This highlights how technology, particularly through social media channels, becomes a tool for political actors to wield power and influence in the political landscape.

Over the past decade, paid political buzzers have wielded considerable influence on Indonesian social media, promoting narratives aligned with President Joko Widodo’s agenda. Concurrently, social media celebrities have been mobilised to garner support for the current Minister of Defence, Prabowo Subianto. These influencers collaborate to saturate social media platforms with political messaging aimed at swaying election outcomes. Whether operating individually or as part of orchestrated campaigns, these buzzers are incentivised by substantial payments for their engagement on social media platforms (Perper, 2018). The 2024 Indonesian election vividly illustrates the impact of technology, particularly in shaping the victories of Prabowo Subianto, who, paired with Gibran Rakabuming Raka, President Jokowi’s eldest son, saw millennial and Generation Z voters significantly shaping the political landscape (Wahid, 2024).

Examining political phenomena through the lens of techno-realism highlights the importance of understanding identity formation in Indonesia’s 2024 presidential election. In this context, technology, especially social media platforms, significantly shapes and reinforces identities among diverse political groups and individuals. The election landscape has been defined by the urgency vocalised by the three candidates: former Jakarta governor Anies Baswedan and Muhaimin Iskandar emphasising “change,” Prabowo and Gibran prioritising “continuation,” and Ganjar Pranowo and former minister Mahfud MD focusing on “improvements.” From this perspective, discussions have shifted towards social media narratives regarding the significance of the future location of Indonesia’s new capital city, emerging as a critical policy question leading up to the 2024 elections. Initiated during President Joko Widodo’s administration, this ambitious endeavour aims to establish Nusantara (IKN), a new capital city, from scratch on the island of Borneo, with an estimated cost of Indonesian Rupiah 466 trillion (approximately US$30 billion) by the year 2045 (Sukma, 2023).

Those supporting the establishment of a new capital city have the option to endorse either the Prabowo–Gibran “continuation” coalition or the Ganjar–Mahfud “improvements” coalition, particularly as the Anies–Muhaimin alliance has expressed intentions to reassess the continuation of this mega project if elected. Defence Minister, Prabowo Subianto, also underwent a significant transformation in public perception, transitioning from a confrontational figure in the 2019 presidential election to a more approachable persona with the help of social media. This rebranding was particularly effective among Indonesia’s younger demographic, who are not familiar with his controversial past or the authoritarian rule of his father-in-law, General Suharto. Prabowo’s image was softened through his portrayals of being a gentle and affectionate figure, including his love for cats. This shift in perception played a role in garnering support from a sizeable portion of the electorate (The Guardian, 2024).

The government of Indonesia also used cyber warfare tactics aimed at attacking opponents by spreading radical, ethnic, and religious issues. The Indonesian government has undertaken various initiatives to combat cyber warfare, including the implementation of the Electronic Information and Transaction Act and the procurement of ICT devices to detect and address the propagation of detrimental content on social media platforms. Social media platforms, such as Twitter (now X) and Facebook, while effective for staying informed, also facilitate the rapid dissemination of negative information, which is often accepted as truth without verification, necessitating law enforcement to utilise adequate digital tools for interrogation to combat effectively the spread of hoax news (Nastiti et al., 2018). There is a surge in politically motivated prosecutions under laws, such as information and electronic transaction law effectiveness (UU ITE), targeting dissenting voices, including students, journalists, and activists (Ufen, 2024). Based on the statistics provided by the Institute for Criminal Justice Reform, between 2008 and 2020, the conviction rate for cases related to cyber law in Indonesia stood at 96.85%, with approximately 88% of the defendants receiving prison sentences (Nugroho, 2024). The Indonesian government’s subpoena of human rights activists, Fatia Maulidianti and Haris Azhar, purportedly for defamation related to mining operations in Papua Province, has drawn criticism from the Indonesian Legal Aid Institute Foundation (YLBHI), which views it as a curtailment of freedom of expression. This legal action highlights the ongoing tensions between activists and government entities regarding the contentious issue of mining in Papua Province (Business & Human Rights Resource Centre [BHRRC], 2021).

3. Third Case Study: The Threat of China’s “Digital Authoritarianism” in the Indo-Pacific Region

The Indian Ocean is a home to rapidly growing economies that are linked to both the Atlantic Ocean and the Asia-Pacific region, making the Indo-Pacific an extremely important geostrategic concept (European Parliament Think Tank, 2023). When analy-sing geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific through the lens of techno-realism, it is essential to recognise the region’s rapid technological advancements. Additionally, understanding identity establishment is crucial, particularly considering the role of political ideology in shaping perceptions of China’s authoritarianism in the region. External powers, such as North Atlantic Treaty Organization, perceive the pursuit of technological dominance as intricately tied to shifting geopolitics in the Indo-Pacific, which is entangled in the ongoing competition between the United States and China. Technologies, including AI, autonomous systems, big data analysis, 5G, biotechnologies, and quantum computing, are poised to significantly transform the region (NATO, 2022, pp. 39–43). At the same time, there has been a concerning decline in democracy across the Indo-Pacific region. Southeast Asia has been particularly affected, experiencing a severe regression, while East Asia and South Asia have also seen a moderate decrease. This trend is part of a global pattern where democracy is diminishing, affecting a diverse range of political systems in the region, including democratic, hybrid, and autocratic regimes (Hudson Institute, 2022).

In accordance with techno-realism, technology is regarded as a significant instrument of power, and its extensive influence extends into the realms of business and investment. While analysing this case study, it is important to look at China’s extensive production of ICT and surveillance equipment, supported by government subsidies and high domestic demand, which has facilitated the global export of affordable digital infrastructure through initiatives such as BRI and DSR. These connections are contributing to the reinforcement of authoritarian tendencies in the digital realm. The proliferation of smart cities, smart devices, and the Internet of Things has greatly expanded the variety and volume of available data, allowing for heightened monitoring of individuals’ daily activities. Furthermore, the emergence of technologies, such as AI and facial recognition, has significantly enhanced governments’ capabilities to analyse data, thereby enabling more efficient surveillance and repression of their citizens (Strub, 2023).

In 2013, China unilaterally introduced BRI, aiming to bolster connectivity and cooperation by investing in and fostering infrastructure ties with neighbouring countries. BRI emphasises five priorities: policy coordination, infrastructure connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and people-to-people bonds. Investment and trade are crucial, and the other priorities focus on infrastructure, policy coordination, financial integration, and public support (Chang, 2019, p. 8). Democratic leaders view BRI as a lasting concern due to apprehensions about risky Chinese technologies, encompassing national security, intellectual property theft, and privacy risks. The DSR enhances China’s connections with Southeast Asian nations through ICT, allowing China to play a significant role in their technological progress (Mochinaga, 2021). The 2019 pandemic provided cover for authoritarian measures, such as restricting movement, suppressing expression, and increasing surveillance, under the guise of public health concerns. This rise in authoritarian governance poses a threat to civil liberties, political rights, and long-term stability in the Indo-Pacific, while established democracies in the region are showing resilience against these trends (Runde et al., 2022, pp. 3–5).

In 2022, Rodrigo Duterte’s administration was accused of controlling the COVID-19 information to conceal pandemic response inadequacies, with social media utilised to propagate false success narratives. Critics face crackdowns under the guise of combating misinformation. Duterte’s rise to power was attributed to “digital authoritarianism,” employing troll armies to smear opponents. Allegations suggest public funds are used to maintain troll farms, prompting calls for investigation. Duterte’s recent veto of a bill requiring real name registration for SIM cards, seen as targeting troll farm operations, reflects the administration’s reliance on social media manipulation (Arlegue, 2022). In the case of the 2022 Philippine elections, for instance, building on the country’s first “social media election” in 2016, a heightened sequel was evident. The pervasive misinformation on social media intensifies divisions, transforming the election into a fierce contest where the tactical deployment of outrage, virality, and trolling may wield significant influence, ultimately shaping the strength or fragility of democratic institutions in the nation (Quitzon, 2021). After being elected, President Bongbong Marcos guided the Philippines in delicately balancing ties with the United States and China amidst ongoing tensions, taking into account China’s territorial disputes and the US Free and Open Indo-Pacific initiative (Baquiran, 2023).

In Indonesia’s 2024 election, the widespread ownership of mobile phones and extensive Internet access allows politicians to engage with residents in remote corners of the country’s expansive archipelago of 17,000 islands. Their primary objective is to attract the support of the significant demographic of 106.4 million young voters, aged 17–40 years, who make up 52% of the overall eligible voters. Analysts stress the importance of securing backing from this demographic as a pivotal factor for electoral success (Yulisman, 2023).

Taiwan faces significant foreign manipulation and disinformation operations, primarily from China, prompting it to adopt a whole-of-society approach to digital democracy, exemplified by initiatives such as the Presidential Hackathon and the Open Government National Action Plan. Despite these efforts, Taiwan’s exclusion from international recognition hampers its ability to engage completely in global discussions on digital governance and undermines its potential to share insights in countering “digital authoritarianism” (Caster, 2024).

In India, attention has shifted to DSR due to its security implications. Viewed as geopolitical, DSR aims to foster economic dependence on China through e-commerce and Fintech advancements like the digital yuan. However, concerns arise over cybersecurity as the DSR technology export could grant China access to sensitive data, posing security risks for India and its neighbours.

In techno-realism, non-state actors are pivotal in shaping technological cooperation. The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), comprising India, Japan, Australia, and the United States, recently formed a “Working Group on Critical and Emerging Technologies” to improve collaboration among states in the region. Emphasising democratic norms, the Quad aims to counter Beijing’s autocratic influence in development of technology. Collaboration in research and development is crucial for gaining a competitive edge against China, with a focus on supporting digital infrastructure in South and Southeast Asia. Initiatives such as the Blue Dot Network and the G7’s Build Back Better World (B3W) complement these efforts, promoting transparent and democratic values in development of digital infrastructure (Panda, 2021).

Conclusion

Political realism has been long criticised for being too state-focused, and some of the theories born afterwards, such as neorealism, offensive and defensive realism, only operate around international issues. In this theory paper, I introduced techno-realism as a more contemporary approach in analysing modern hybrid challenges in politics from domestic to international, under the umbrella of political realism, as a continuation of its development after Mearsheimer’s (2003) offensive realism. This theory operates with technology in the centre of political processes, which extends to investments in businesses, science, and defence technology, and returns to the advancement of human resources and economy of the state. Techno-realism emphasises an important process of identity formation in politics to overcome the complexity of root-cause analysis using political realism. According to techno-realism, identity establishment can be divided into religious, national (as examined in the Xinjiang case study), urgency (as examined in the Indonesia’s social media case study), and political ideology (as examined with regard to the “digital authoritarianism” threat in the Indo-Pacific). States, according to techno-realism, are also not the only actors in politics; the theory recognises how non-state actors, such as the technology industry, for example Big Tech, bilateral and multilateral partnerships, for example Quad, 7G, Shanghai Cooperation, and others, have an influence.

In examining the interplay between religious identities and cyberpolitics’ measures in Xinjiang, it is crucial to identify the foundational concepts and political framework enforced by states. While China prioritises stability, its political opponents perceive it as genocide, and for many, it represents oppression and violation of human rights. This research examined one important element that is used in fostering China’s national interests in the Xinjiang region through technological means. In the context of Xinjiang and applying techno-realism, two main standpoints emerged. Firstly, the fear of instability serves as justification for China’s policies in the region, where the Chinese government employs an “ideology against ideology” approach and integrates the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation’s “three evils” into its deradicalisation narrative.

Secondly, according to techno-realism, technology serves as a source of power while recognising the role of non-state actors in political struggles. This is evident in the Chinese government’s endeavours to maintain control in Xinjiang through various cyber measures, including cyber attacks on Uyghur activists, cyber espionage facilitated by mobile apps and malicious websites, and deployment of advanced surveillance systems, biometrics, and facial recognition technologies, which often result in involuntary relocation of the Uyghurs to re-education centres. Additionally, Chinese Big Tech’s technological products are utilised to curtail the freedom of the Uyghur population.

In the context of Indonesia’s 2024 presidential election, technology’s role is evident through social media platforms, serving as both tool for electoral success and social control via the “rubber law” UU ITE, often targeting activists and researchers. During this election, the pairing of Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto and President Joko Widodo’s eldest son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, garnered significant sympathy through social media. Through the lens of techno-realism, the urgency surrounding the new capital city phenomenon (IKN) played a pivotal role in splitting votes, ultimately contributing to the continuation of status quo. Investment in “political buzzers” and influencers on social media platforms further influenced the outcome of the election.

The Indo-Pacific, on the other hand, has ideology of technology at play; the region is currently facing the narrative of “digital authoritarianism” and the region emerges as a focal point of geopolitical significance driven by rapid technological advancements and complex identity dynamics. As viewed through the lens of techno-realism, the pursuit of technological dominance intertwines with shifting geopolitics, particularly evident in the rise of China’s DSR initiative and its implications for regional security and governance. The trend towards authoritarian governance, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, poses significant challenges to democracy and civil liberties across the region.

Cases such as those in the Philippines and Indonesia underscore the pivotal role of social media in shaping political narratives and electoral outcomes. Meanwhile, Taiwan’s innovative approach to digital democracy faces hurdles due to its international isolation. In India, concerns over cybersecurity and technological dependency on China highlight the importance of collaborative efforts, particularly among non-state actors, such as the Quad, to promote transparent and democratic values in technology development and infrastructure investment. These initiatives, alongside broader international partnerships, such as the Blue Dot Network and the G7’s B3W initiative, offer avenues for countering authoritarian influences and fostering a more inclusive and resilient Indo-Pacific region.

Techno-realism emerges as a promising theoretical framework for analysing contemporary political challenges, bridging the gap between traditional state-centric approaches and the complex realities of the digital age. By placing technology at the centre of political processes and recognising the agency of non-state actors that are inevitably important, techno-realism offers valuable insights into the interplay between technological advancements, identity formation, and power dynamics in domestic and international politics.

However, like any theory, techno-realism requires further testing and refinement to understand completely its applicability and limitations across different contexts. As demonstrated in the case studies of Xinjiang, Indonesia, and the broader Indo-Pacific region, techno-realism provides a nuanced understanding of how technology shapes political narratives, electoral dynamics, and regional security concerns. Moving forward, scholars and policy-makers can benefit from integrating techno-realism into their analyses to navigate the complexities of contemporary political landscapes and inform strategic responses to emerging challenges in the digital era.