Introduction

The drastic changes in the European security environment have drawn attention back to war and its practical expression: warfighting. Regarding this renewed interest, one area—organised violence between opposing land forces—has taken the centre stage, as it faces profound shifts in the employment of force on the battlefield (Nilsson and Weissmann, 2023, pp. 1–6). In relation to these developments, are the doctrinal provisions of the leading Allied powers on the range of land military operations still relevant? This conceptual paper argues that the answer is negative, as current military operation typologies remain overly anchored on the offensive, defensive, and stability operations framework, leaving resistance outside of their scopes.

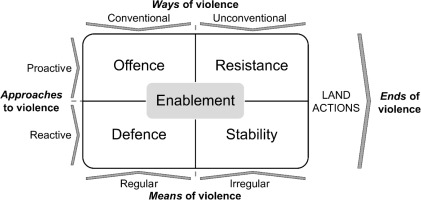

To address this gap, the paper introduces a new conceptual framework based on five “warfighting directions”: offence, defence, enablement, stability, and resistance. They are defined as core modes of land action that can be applied across a continuum and spectrum of violent engagements. The newly introduced concept of warfighting directions is presented with the assumption that it can capture what various military doctrines attempt to describe using terms like “elements of warfare,” “tasks in the range of military operations,” and “land tactical operations.” Grounded in the principle that “plain terms are needed to command” (German Army, 2018, p. 44), the framework seeks to describe how these five warfighting directions are generated and what sources underlie their appearance.

The proposed framework is shaped by the existing theoretical outlooks that define traditional (regular and conventional) and newer (irregular and unconventional) forms of warfare.1 One approach, the “generations of warfare” concept, seeks to categorise the historical evolution of warfare into distinct “generations” (Lind et al., 1989). Although highly criticised, the concept has merit, as it provides information on how military operations have evolved in relation to the different forms of warfare. The concept is practical if “future research on land tactics should attempt to unite two lines of thought,” thereby bridging conceptual divides, as Nilsson (2021, p. 382) concludes.

The paper follows the lead of previous works and advances even further. It reconceptualises the range of land military operations to provide a shared framework for Allied militaries that are doctrinally closely interlinked. Therefore, the first part involves a critical but brief literature analysis of the dominant theoretical perspectives, linking core modes of land action with their sources. The second part is a brief comparative study of the closely interlinked Allied doctrines. The inquiry into the current typologies of military operations found in North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), US, UK, and German army- doctrines highlights that they do not account for resistance as a core mode of land action, albeit an emerging operational reality requires them to do so. The third part defines the framework of warfighting directions using the knowledge-mapping technique.

Limitations apply. The paper should be considered an intellectual exercise seeking a better description of the same warfighting reality from a new perspective. Even so, the framework is designed to assist state-centric Allied armies primarily acting in the land domain. Therefore, interpretations are made through the lens of violence, although some forms, such as unconventional warfare, promote the use of non-violent methods at first. In addition, the framework is designed for the tactical level, but operational- and strategic-level decision-makers can also use it. Also, for this paper, accessing relevant documents was challenging. Nevertheless, despite its limitations, this paper can provide a better understanding of the core modes of land action, or at least spark further studies on an urgent issue.

Advanced warfighting unravelled

The concept of generations of warfare offers early insights into why currently used typologies of military operations in the land domain may be ripe for revision. Introduced by Lind et al. (1989) to explain the evolving character of warfighting, the concept outlines distinct generational shifts. In the first generation, battles were fought using mass forces as well as line and column tactics. The second generation emphasised attrition and firepower. The third generation introduced manoeuvre warfare, characterised by non-linear tactics, combined arms, and mission command (Lind et al., 1989, p. 23; Lind, 2004b, pp. 12–13). In terms of these generations, warfighting can be framed as “regular and conventional”—where one side attacks and the other defends—although manoeuvre warfare already disrupts classical warfighting norms (US Marine Corps, 2018, pp. 2–12).

The classical perspective leaves a simple imperative. “All actions in war, regardless of the level, are based upon either taking the initiative or reacting in response to the opponent” (US Marine Corps, 2018, pp. 2–11). To put it simply, offence is the result of a proactive approach to violence, while defence is the result of a reactive approach to violence. These two basic approaches to violence—classical military strategies—are the first generative dimension of violence, studied and debated for thousands of years, from Sun Tzu to Carl von Clausewitz, Jomini, and beyond.

However, modern approaches to violence involve more nuanced engagements than a classical military view suggests. Today, advanced warfighting employs a vast spectrum of enabling operations, rather than just following the “take the initiative or respond to it” pattern. This shift is linked to the transition to third-generation warfare—manoeuvre warfare—which emphasises non-linear tactics, deep penetrations behind enemy lines, and a preference for the time factor over space (Grauer, 2016, pp. 15–60; Lind et al., 1989, p. 23; Nilsson and Weissmann 2023, p. 3).

Enablement, in this context, refers to the synchronised use of forces and assets (enablers) that make manoeuvre and operational transitions possible in non-linear warfare. It encompasses timely reconnaissance, breaching capabilities, logistics, bridging units, fires, and other capabilities. It now also includes modern capabilities, such as cyber/information operations and strategic communication. Without these, non-linear operations are just not possible. Moreover, the more complex the force structure at different levels is, the greater the variety and sophistication of enablers required.

These enablers allow land forces to operate in combined arms formations under a unified command, even integrating non-military assets (German Army, 2018, p. 33). For example, transitioning from offence to defence necessitates well-coordinated withdrawal and proper entrenchment, while a shift from defence to offence demands a fusion of scouting and movement. Similarly, transitioning from defence to resistance requires adept infiltration and exfiltration techniques as well as proficiency in ambushes. Enablement, therefore, serves as a connective mode across transitions in modern warfare.

The first three generations of warfare adhered to the traditional state-based conflict model. The so-called fourth-generation warfare, in contrast, follows a different logic. It emphasises the diffusion of authority to use violence from the state and military forces to non-state actors (Nilsson and Weissmann, 2023, p. 3). In this context, warfare becomes idea-driven, fought by regular and irregular forces—even without state approval—and, often, civilians are directly involved in conflicts (Lind, 2004b, pp. 13–14; Lind et al., 1989, pp. 25–26).

The notion of irregularity gained renewed attention around 2001, as military thinkers sought new ways to understand “new” military endeavours that did not fit traditional models (Salmoni 2007, p. 18). As a result, stability operations—focused on peacekeeping, counter insurgency, and reconstruction—were included in military doctrines alongside offence and defence. This aspect of war was given equal priority with others (Derleth and Alexander, 2011, p. 125).

However, the concept of fourth-generation warfare is highly contested. Critics, such as Echevarria II (2005, pp. 10, 13), argue that irregular conflicts have always existed alongside regular warfare and are not unique to a new “generation”. According to this view, forms of warfare evolve continuously in parallel, rather than in distinct stages. Similarly, Curtis (2005, pp. 31–32) and Junio (2009, p. 259) contend that “fourth generation” is less a new stage of warfare than a repackaging of long-standing insurgent tactics under a new label rooted in the irregular warfare tradition. Hoffman (2007, 19) goes further, arguing that “the fourth-generation framework hides more than it reveals,” suggesting instead that “hybrid warfare” may offer a clearer lens.

Despite the criticisms, the concept offers valuable insights into how today’s conflicts are fought, as follows. First, Junio (2009, pp. 243, 267, 259) criticised the concept for lacking grounding in military history, suggesting that its value lies more in ideas about the current and future character of warfighting. Therefore, fourth-generation warfare should be considered through the lens of insurgency, grounded in irregular warfare. Second, as Echevarria (2005, p. 11) points out, regular or irregular attack on the enemy is still a means of violence—the tools and methods by which force is applied—to the same end: to break the enemy’s will. This is just another source of organised violence. Lastly, Junio (2009, p. 267) advocates for a balanced approach, in which the military must be prepared to fight both regular and low-intensity conflicts simultaneously. In this regard, Hoffman (2007, 2010) promotes the fusion of various forms of warfare to respond effectively to emerging hybrid threats. Benbow (2008, p. 153) warns that broadening the concept of warfare too much can be misleading and dangerous with regard to the use of military force. This paper acknowledges these insights and uses them to develop a conceptual framework for defining warfighting directions.

Vocal criticism of the fourth-generation warfare concept did not diminish its influence. Instead, debates over its limits—alongside the rise of the digital age—contributed to the emergence of what many now refer to as fifth-generation warfare. This concept priori-tises the use of non-violent influence to counter hostile narratives and shape public and global opinions. In this context, conflict is perception-driven or information-driven, relying on cyberattacks, media manipulation, and psychological operations to achieve strategic effects, avoiding direct military confrontation (Krishnan, 2022, p. 17; Nilsson and Weissmann, 2023, p. 3).

Surprisingly, the fifth-generation warfare concept has received only a few critical notes, despite remaining loosely defined. An early critic, Lind (2004a), argues that the concept is merely an initial stage of fourth-generation warfare, which is still in development. Barnett (2010) concludes that both fourth and fifth generations are hostages to their faulty assumptions within the limited paradigm. What is crucial is that the concept radically departs from the centrality of violence. Violence was, is, and will be the fundamental component of war. Therefore, warfighting, primarily, is an organised application of violence to achieve political ends, as Huntington concludes (1957, p. 11). Without violence, the purpose of warfare as well as the military is dishonoured. Even if the concept is accurate, who can overlook that the fifth-generation warfare only attempts to weaponise normal societal change in the digital age? According to Sharp (2010, pp. 39–45), any non-violent struggle must be organised by a state, actor, or someone else. Without such proof, the fifth-generation warfare remains only an unstable yet popular theoretical school.

Again, despite the criticisms, the concept offers insights if viewed through the lens of how wars are fought. First, fifth-generation warfare should be considered as a strategic-level concept, which the military becomes involved in when the conflict escalates into covert or overt violence. Second, fifth-generation warfare is a form of unconventional warfare that has been adapted to the digital age (Reed, 2008, p. 716). In this context, resistance— grounded in the unconventional and irregular warfare tradition—is a typical proactive strategy. It is applied indirectly, through highly controlled and psychologically targeted ways, both violent and non-violent (Kilcullen, 2019, pp. 67–68). Finally, advances in digital technologies, such as social networks and artificial intelligence, should make unconventional ways of violence even more accessible to complement conventional ones (Tovo et al., 2024, p. 30).

In this context, numerous proofs justify why resistance, the fifth warfighting direction, has matured as a concept to take its rightful place among the other four. Osburg (2016, p. 2) explains in practical terms how unconventional options, through “aggressive resistance activities,” could benefit the land-based defence of the Baltic States. Fiala (2020) provides a Resistance Operating Concept (ROC) suitable for military operations. Kilcullen (2019, p. 70) addresses the need to integrate resistance strategies into multi-domain operations. But perhaps, the most compelling evidence is the employment of resistance in the large-scale war in Ukraine.

Historically, resistance as an unconventional warfare form has been an exclusive authority of Special Forces. However, today’s operational realities dictate that unconventional warfare can no longer be their sole responsibility, even if it should remain under their supervision (Maxwell, 2013, 2023). Ukraine offers a living, still-evolving example. It is the first nation to codify a national resistance strategy into law, encompassing both covert and overt, as well as violent and non-violent, aspects, and to formally integrate resistance into its military structure and operations (Fiala, 2022).

In the Ukrainian case, the resistance framework takes three forms: societal resilience, national resistance in controlled territory, and resistance movements within occupied and hostile terrains. The first one includes various nationwide non-violent activities aimed at strengthening “people’s will to maintain what they have, including their ability to withstand external pressure and influences” (Fiala, 2022). National resistance refers to a structured organisation of societal and military elements. This form is primarily carried out by the territorial defence forces, a component of the Ukrainian armed forces, to prepare regions for defence and resistance while they are not occupied. The third form, resistance movements, refers to network-based, covert organisations operating within occupied and hostile areas. Led by special forces and executed by proxy actors, they seek to restore territorial integrity and make strategic impacts that extend deep behind enemy lines by employing a diverse range of civilian, military, and informational assets (Fiala, 2022; Ministry of Defence of Ukraine, 2025).

After more than 3 years of large-scale military conflict, the utility of resistance can be evaluated based on first hand combat experience. According to Armstrong (2025, pp. 22, 24, 27, 30), Ukraine’s resistance movement in occupied areas has demonstrated a wide range of capabilities despite a proven and brutal Russian security apparatus. However, as evidence shows, the utility of resistance was reduced due to its weak pre-war preparation and the overall integration with the Ukrainian armed forces.

In parallel, Ukraine’s resistance movement within hostile territory has demonstrated that unconventional capabilities can effectively compensate for the lack of conventional long-range ones. The spectacular attacks not only had operational impact but also psychological and informational effects, both locally and globally (Laufer and Atwell, 2025). Together with intelligence, targeted sabotage, assassination, and other unconventional capabilities, resistance has become a tangible force multiplier for land operations (Ashour, 2025). Yet, as the following section shows, resistance is still not recognised in military doctrines as a core mode of land action.

The same warfighting realm but different conceptual approaches

The comparative analysis of selected military doctrines, as summarised in Table 1, leads to several insights. The core finding is that despite different conceptual perceptions of the factors causing land action, the warfighting directions of all doctrines are almost identical—generally including offence, defence, stability, and enablement. Named “elements,” “operations,” military, or tactical “activities” and “tasks,” they all account for core land-based actions that can be taken across a continuum and spectrum of violent engagements (NATO Standardization Office (NSO), 2023, pp. 13, 55–56; US Department of the Army, 2025b, p. 12; US Marine Corps, 2018, pp. 2–11). Therefore, it makes sense to use the warfighting directions as a general concept if the conceptual framework of their creation is provided.

Table 1

A comparison of the conceptual approaches to strategic trajectories of land action found in the doctrines of NATO land forces, the US army, the US marine corps, the UK land forces, and the German army.

| Case | Factors behind the creation of land action | Strategic trajectories of land action |

|---|---|---|

| US Army | Warfighting functions: Friendly systems and tasks generate combat power (US Department of the Army (2025a), p. 22) Employed through: Conventional and irregular warfare (US Department of the Army, 2025b, pp. 8–9) | Inherent elements of conventional and irregular warfare: • Offensive operations • Defensive operations • Stability operations (US Department of the Army, 2025b, p. 2) |

| US Marine Corps | Physical, moral, and mental forces (US Marine Corps, 2018, pp. 1-14–1-15) Employed through: Initiative and response Offensive and defensive warfare Speed and focus Surprise and boldness (US Marine Corps, 2018, pp. 2-11–2-14, 2-19–2-23) | Tasks in the range of military operations (ROMO): • Offensive task • Reconnaissance and security task • Stability task • Defensive task • Other tactical operations (US Marine Corps, 2019, p. 2-1) |

| NATO land forces | Moral, conceptual, and physical components of fighting power influenced by context (NATO Standardization Office (NSO), 2023, pp. 17–21) Employed through: • Manoeuvrist approach • Manoeuvre warfare • Mission command • Joint action (NATO Standardization Office (NSO), 2023, pp. 37–41) | Land tactical operations: • Defensive • Offensive • Stability Tactical activities: • Offensive • Defensive • Stability • Enabling (NATO Standardization Office (NSO), 2023, pp. 54–56) |

| UK land forces with a focus on the British Army | Components of fighting power: • Conceptual (the thought process) • Moral (the will) • Physical (the means) (Ministry of Defence of UK, 2023, pp. 34–37) Employed through: • Manoeuvrist approach • Combined arms approach • Mission command (Ministry of Defence of UK, 2023, pp. 37–38) | Types of operations: • Combat • Stability • Military aid to the civil authority Tactical activities: • Offensive • Defensive • Stability • Enabling (Land Operations, UK, 2017, pp. 2-6–2-7) |

| German Army | Forces and assets (including non-military); Skill and mental prowess (German Army, 2018, p. 15) Employed through: • Mission command • Comprehensive approach • Effects-based thinking • Combined arms operations (German Army, 2018, pp. 27–35) | Tactical activities: • Offensive • Defensive • Stability • Enabling • Supporting (German Army Officer School, 2022) |

The results of the comparison also reveal that current doctrines are centred on third-to fourth-generation warfare, leaving behind important aspects of the fifth-generation warfare. On the one hand, doctrines strongly emphasise speed, surprise, shock action, and destruction—critical aspects of manoeuvre warfare (NATO Standardization Office (NSO), 2023, p. 37). Since they encompass combined arms and mission command traits, doctrines logically appreciate land action created by military forces and their enablers, including non-military ones.

On the other hand, doctrines recognise the vital role of irregularity. With particular reference to the US Army, as well as the UK land forces, doctrines acknowledge that future warfare is not just about conventional warfare (Ministry of Defence of UK, 2023, pp. 49–50; US Department of the Army, 2025b, pp. 8–9). The broader need for synergistic approaches in future combat is also highlighted by Laufer and Atwell’s (2025) findings.

However, the unconventional warfare part is somehow excluded from the list of land actions and is left mainly to the special operations (Ministry of Defence of UK, 2023, p. 50; US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM), 2016, p. 4). Maxwell (2013) disagrees with this and argues that “unconventional warfare cannot ‘belong’ solely to one military force, nor even to the military alone. It is a strategic mission that is an offensive option for policymakers and strategists.” As Kilcullen (2019, p. 61) further highlights:

The assumptions underpinning traditional unconventional warfare have diverged from reality in the last two decades. These include the idea that unconventional warfare occurs mostly within denied areas; […] and the assumption that the external (non-indigenous) component of unconventional warfare primarily consists of infiltrated special forces elements, or support from governments-in-exile. Arguably, these assumptions were always theoretical attempts to model a messy reality. But since the start of this century, the evolution of resistance warfare within a rapidly changing environment has prompted the unconventional warfare community to reconsider their relevance.

In summary, there is a simple reason why resistance remains absent from the basic land action list: the value of unconventional methods of violence, a part of fifth-generation warfare, has yet to be fully recognised. For example, in the 2000s, irregular warfare’s significance was recognised, albeit under shocking circumstances, which led to the conceptual inclusion of stability operations alongside traditional combat actions—offence and defence (Derleth and Alexander, 2011). Therefore, a conceptual framework outlining the rationale for the emergence of the warfighting directions—core modes for land action that can be taken across a continuum and spectrum of violent engagements—could serve the purpose of resistance inclusion. The following section proposes such a conceptual framework.

Conceptualising warfighting directions

Few would dispute that the definition of warfighting begins with a picture of organised violence between opposing forces in a combat. While violence remains a foundational element of warfighting, its organisation requires conceptual recalibration to address the latest advances in warfare. The proposed framework challenges traditional binary warfare perspectives, such as those of offensive versus defensive, regular versus irregular, and conventional versus unconventional. Rather than viewing warfighting in strictly binary terms, this paper presents how offence, defence, stability, resistance, and enablement originate from violent constituents. Following Lykke’s (1989) teachings on military strategy, it is argued that organised violence arises from the following three sources: (1) the “approaches to violence,” which address combat problems in order to reach desired “ends” concerning “risks”; (2) the “means of violence,” which create destructive forces; and (3) the “ways of violence,” through which violence operates. Figure 1 illustrates how these dimensions interact to create warfighting directions of land action.

The first dimension, particularly vital in first- to third-generation warfare, involves whether violence is employed “proactively” or “reactively” to address combat challenges. Proactiveness pursues gains through initiative, momentum, and instrumental aggression (Larson et al., 1986, pp. 387–389; US Marine Corps, 2018, pp. 2-11–2-14; Walters, 2005, p. 29). It leads to either offensive operations in conventional and regular warfare or resistance actions in unconventional and irregular warfare (Fiala, 2020, p. 5; US Marine Corps, 2018, pp. 2-11–2-14; US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM), 2016, pp. 5, 28).

In contrast, a reactive problem-solving approach is driven by necessity, passivity, and impulsive aggression in response to provocations (Larson et al., 1986, p. 385; US Marine Corps, 2018, pp. 2–12; Walters, 2005, p. 29). Accordingly, reactive violence generates defensive or stability efforts based on the situation (Derleth and Alexander, 2011; US Marine Corps, 2018, pp. 2-11–2-14).

The second dimension concerns whether violence appears in a regular or irregular form. Regularity encompasses two aspects. The first aspect pertains to the regularity of armed structures, encompassing requirements such as being commanded by a responsible individual, having a recognisable, distinctive sign, openly carrying arms, and conducting operations by the laws and customs of war (Fiala 2020, pp. 91–93).

The second aspect relates to the regularity of the means used in warfighting. Generally, regular means must adhere to military-like standards involving using conventional arms and equipment suited for standard military tactics and procedures. Therefore, regular warfare, as a rule, involves professional armed forces focused on open conflict for terrain control, with one side on the offensive and the other on the defensive.

Irregularity, a manifest of fourth-generation warfare, works differently. Irregular formations tend to operate in erratic organisational forms, even though they copy elements of regular forces. In addition, the means of violence employed are often unorthodox, sometimes leading, but not necessarily, to unconventional ways of fighting. The range of tools and tactics available is extensive, limited only by the imagination, yet violent means are preferred (Qureshi, 2019, p. 208). Because irregular forces are adept at employing diverse tools and methods, they are experts in their own right. With the focus on population, not terrain, and the diffusion of authority to use violence away from the state and military forces, such as the use of non-state actors, the warfighting direction of stability emerges as a reactive mode of land action to counter irregular forces, employing unconventional ways of fighting (Qureshi 2019, pp. 209–210).

The third dimension concerns whether violence is carried out through conventional (traditional) or unconventional (non-traditional) ways. One aspect of conventional violence involves traditional military strategies and tactics, typically employed by regular forces. Another aspect concerns the use of military force according to national and international legal frameworks, including the law of war, the law of armed conflict, international humanitarian law, and international human rights law (Fiala 2020, pp. 85–98). With the use of conventional violence, the aim is to gain state control by defeating the enemy’s military forces through traditional warfighting methods (Lindsay, 1962, p. 264). Therefore, conventional and regular warfare have much in common when discussing traditional land actions—offence and defence.

Unconventional warfare marks a major disruption of warfighting due to the incorporation of non-violent fighting methods into combat (Nilsson and Weissmann, 2023, p. 3). Bonded to fifth-generation warfare, today’s unconventional way of fighting aims to gain control of the state by first winning control of the civilian population without the use force. The need to dominate information, perception, and narratives is, therefore, a logical response to the emergence of new domains of conflict, such as the cyber, physical, information, cognitive, and social domains (Reed, 2008, p. 691).

However, unconventional warfare does not renounce the use of violence (Reed 2008, p. 691). Instead, it embraces the unorthodox use of standard weapons, including the weaponisation of civilian means and innovative strategies and tactics (Tovo et al., 2024, pp. 25–27). In extreme cases, it can even disregard legal frameworks and international law. As a result, unconventional and irregular warfare overlap when discussing unorthodox land actions: stability and resistance.

What is essential is that unconventional methods are a part of the conventional battlefield. Historically, unconventional ways of violence, common under irregular formations, have supplemented or even substituted for conventional forces (Tovo et al., 2024, pp. 21–25). The recent experience in Ukraine demonstrates that the resistance movement, which is an unconventional, irregular, and proactive tool, provides significant added value for large-scale combat scenarios (Laufer and Atwell, 2025). Therefore, unconventional methods should also play its rightful role in large-scale combat operations. Adding resistance to the list is a logical conclusion, as suggested by the proposed conceptual framework.

This framework offers an alternative explanation of how warfighting directions of land actions are developed, conceptually. Offence—an essential mode of land action to achieve victory in combat—stems from a combination of regular forces, conventional methods, and a proactive strategic approach to violence. In parallel, defence—a mode to create conditions for an offensive—is the outcome of employing regular forces, conventional methods, and a reactive strategic approach to violence. Similarly, resistance—a valuable mode of warfighting when open confrontation is not possible—derives from the use of irregular formations and proactively employing unconventional methods. Stability aims to counter insurgencies and maintain control in governed, contested, and post-conflict areas. Although regular forces can conduct stability operations, stability is best used when irregular formations and unconventional methods are applied reactively. Finally, enablement functions across all modes of land action. It plays a crucial role in facilitating offensive, defensive, resistance, and stability operations as well as ensuring smooth transitions between them.

However, this paper does not claim that any warfighting direction can sustain itself indefinitely, nor can it exist in one perfect shape. Instead, following the US Marine Corps (2018, pp. 2–13) doctrine’s pattern, it is accepted that there exists no clear division between offence and defence nor resistance and stability. Each warfighting direction exists “simultaneously as necessary components of each other, and the transition from one to the other is fluid and continuous.” For this reason, the framework offers a clearer understanding of the development of warfighting.

Conclusions

This paper argued that resistance should be used in land operations alongside offence, defence, stability, and enablement. In this regard, an advanced notion of warfighting was presented first. Addressing the fifth-generation warfare needs, the paper justified why accepting resistance as a warfighting direction is logical and necessary. Subsequently, a comparison of selected military doctrines related to land operations highlighted the need for conceptual recalibration, as they overlook the value of resistance operations. Particularly, resistance is relevant as it has proved its utility in large-scale combat scenarios, as seen in the war in Ukraine. Finally, the paper introduced a conceptual framework by explaining how five warfighting directions are produced. By bridging two lines of thought on warfare—traditional (regular and conventional) and newer (irregular and unconventional)—the framework provides a conceptual basis for acknowledging resistance as a mode of land action.

Although the paper did not provide new insights into military operations, the taxonomy of warfighting directions has several benefits. First, the framework explains how six factors— proactive and reactive approaches, regular and irregular means as well as conventional and unconventional ways—are organised to achieve ends by employing five warfighting directions. By linking military strategy to the core modes of land action, which can be taken across a continuum and spectrum of violent engagements, the framework helps to organise violence effectively and supports commanders in military planning.

Second, the paper advocates for improved interoperability among different Western armies. By framing warfighting not as a sum of isolated actions but as a unified spectrum of modes for land action, the framework empowers doctrinally close Allied armies to synchronise their concepts with overarching aims, at least at a tactical level.

Lastly, the systemic perspective on warfighting proposed can be regarded as a tool for controlling organised violence. The underlying forces that create warfighting directions provide a solid basis for interpreting and applying them equally in political and military decisions. Also, the proposed framework is helpful in countering specific enemy strategies effectively. It helps to oversee how military operations align with operational reality and legal considerations. As a result, it alerts decision-makers to the operational risks posed by the different modes of land action applied. Thus, a more coherent fusion of efforts in military operations in the land domain can be expected if the proposed conceptual framework is embraced. Yet, the viewpoint expressed requires further discussion.