Introduction

The global effect of the COVID-19 pandemic was expected to continue to have huge consequences for health security, the economy, finance, and social life in 2022. On top of this, 2022 saw the beginning of a major conflict in Europe that exacerbated the existing global crises and started new ones in energy, refugees and food distribution. The conflict began in February 2022 with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and is considered to be the most demanding and strange conventional war since World War II, despite the fact that the Russian President, Vladimir Putin, called it a “Special Military Operation.”1 Although it is considered below the level of war according to Russian Military Doctrine, its duration, political objectives, participants and of the way it has been conducted demonstrate that it is a true conventional conflict, which has major implications for the current European order, as it is taking place on the continent’s eastern flank, and for the international security environment as a whole. The Kremlin also tried to implement General Gerasimov’s 2019 vision of “Limited Action” and “Active Defence,” and to continue with certain old tactics and techniques of 2013’s “Non-linear Warfare” Strategy (called “Hybrid Warfare” by the West), which were initially experienced in Ukraine and later on in Europe. The new doctrine therefore combines conventional operations with hybrid actions and the nuclear threat. When 2023 began, the world was able to commemorate not just 1 year of conventional war started by Russia, but 9 years of hybrid actions undertaken by Moscow against Kiev and the West.

In the existing scientific literature, there are numerous ideas and debates as to what hybrid warfare means and how its actions act as enablers for conventional operations. Actions like cyber attacks, disinformation, propaganda or other forms of covert activities represent coercive methods to either shape the Theatre of Operation (ToO) in order to ensure enough political pressure to allow conventional military operations to achieve desired strategic objectives, or to directly achieve political objectives, both nationally and regionally. Therefore, this paper will clarify some aspects of how conventional operations and hybrid actions being conducted by Russia since February 2022 have worked together in Russia’s national interests to maintain its status of regional power and even return it to superpower status.

Unfortunately, international diplomacy couldn’t bring about an effective resolution to this war. The position of NATO was unique, because none of the two belligerent countries—Russia and Ukraine—were member states. Even if both actors have special partnership status with NATO (the NATO-Russia Council and NATO-Ukraine Commission), there is a huge difference in how it treats Russia and Ukraine. While the relationship with Moscow was frozen after 2014, NATO is eager to increase its ties with Kiev as much as possible, transforming the Alliance into a close ally of Ukraine. The situation is very different to what happened in 2008 in Georgia and 2014 in Ukraine including NATO’s response to the events. Neither Georgia nor Ukraine was member of the EU either. The UN was also in a difficult situation, because Russia is a permanent member in the Security Council and has “veto” rights. This is why the first diplomatic reaction was slow and the rhetoric mild and it didn’t deter Moscow’s from its offensive intentions or stop the war from starting. These international and regional security organisations could only use political, economic and informational means and not directly militarily intervene in the conflict. Instead, the International Community encouraged member states and partners to take all necessary measures to support Ukraine and sanction the Russian Federation, and to sell arms to the Ukrainian Armed Forces and engage in soft military participation for advice and expertise.

This paper uses the analytical method of research, which is well described by Professor Clifford Woody as a search for knowledge through objectives using a systematic method to find a solution to a problem, focusing on understanding the cause-effect relationship between the war itself and its future influence on European and global security. To achieve this, the article scientifically analyses the existing data and information regarding what has been happening in Ukraine since February last year in the political-military domain, in both conventional and hybrid senses, and attempts to answer the question: “Are there any lessons identified so far that can possibly influence European and Euro-Atlantic security?” This, in fact, represents the main problem to solve. In order to solve it, the article’s hypothesis starts from the consideration that even though we are not at the end of the war in Ukraine and no belligerent is able to claim victory so far or declare that they have achieved their political objectives, there are some lessons that can be identified for the military field that should be considered for the future security of Europe and the international environment as well. These lessons have and will continue to have geopolitical implications for Europe and the Euro-Atlantic area, with some national consequences as well. The following section describes what was considered as conventional war in the Ukrainian ToO and what types of hybrid actions the Kremlin undertook against either Kiev or Western capitals. The section will outline the evaluation of facts and information related to the research being conducted. It is followed by the forming of a hypothesis through some lessons identified from the first year of the war, outlining their importance at all levels of conflict—strategic, operational, and tactic. The final section will then look at possible implications for regional and national security, in order to develop the best possible solutions for solving the regional situation and re-establishing a positive status quo. It will also theoretically test those implications to determine whether they fit the specified hypothesis. The lessons identified in the scientific research will also highlight leverage points for military training and doctrine development in the future in the face of 21st century modern warfare which, in turn, represents the paper’s contribution to scientific research in the military field. By demonstrating the possible implications of some of those lessons for the regional and international security environment, the results will contribute to a better understanding of what challenges the current world order might face.

Conventional Operations versus Hybrid Actions in the Ukrainian War

In order to conduct a thorough analysis of what happened in Ukraine in the first year of the Russian invasion, we should try to answer to a very demanding question: “Does the actual conventional conflict represent a continuation of the Russian Hybrid War conducted in Ukraine and later extended towards Europe?” In fact, this represents the sub problem to be solved by this section, using the evaluation method of existing data and information. Why did Russia start/restart the conflict last year and why was a new armed confrontation necessary after 2014? Trying to understand the Kremlin’s position in the region and its strategic interests and vision is complicated.

Before starting the evaluation, let us clarify the two terms—conventional operation and hybrid warfare—and how they support each other. Conventional operations use conventional weapons (not chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear ones) and battlefield tactics between two or more states in an open confrontation, in which forces are well-defined and fight using weapons that target each other’s military power. The existing factors (like the increase in the number of nuclear powers, international terrorism and technologically advanced weapons) and the last decade’s military conflicts demonstrated the decreasing importance of such type of warfare, as well as its limits. (van Creveld, 2004, pp. 1, 12). This is why General Gherasimov’s vision of enabling and supporting a conventional operation through other types of warfare, including hybrid actions and nuclear deterrence, remains a masterpiece of military strategy in these times. Hybrid warfare was first described by Frank Hoffman in his paper issued by the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, in which “Hybrid Wars can be waged by states or political groups, and incorporate a range of different modes of warfare including conventional capabilities, irregular tactics and formations, terrorist acts including indiscriminate violence and coercion, and criminal disorder” (Hoffman, 2007, p. 58). But his idea on Hybrid Wars was strictly related to the Israeli-Arab conflict and Hezbollah’s involvement in it. This is why, following the Iraq and Afghanistan phases of the Global War on Terror and the 2014 Ukrainian crisis, this definition was expanded by General Phillip Breadlove, former SACEUR, to include four new components: diplomatic warfare to break existing state-to-state agreements, dissolution of alliances and states that lack international support; information warfare to influence the population and the international community by spreading false images and information; covert and unattributed use of military power for coercion; and economic warfare such as blackmail, sanctions and inflation (Jacuch, 2022, pp. 157–180).

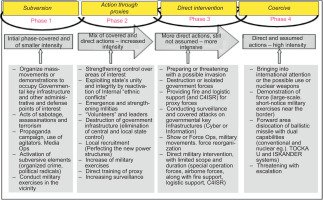

Immediately after the Ukrainian crisis of 2014, a group of Romanian military experts started to think about and assess what the new type of hybrid warfare represented and what kind of threat it might pose for NATO and national security. In this assessment, hybrid warfare was defined as “that type of warfare waged by one of the belligerent parties using both conventional military means and non-conventional or non-military means, simultaneously.” (Cebotari, 2015, pp. 25–26). Moreover, this was amplified by the Kremlin’s “nuclear warning,” as part of its strategy of political intimidation, as well as the danger of blurring the boundaries between peace and war. But once the strategic objective, the means and the method of its implementation, were recognised, it was not difficult to understand the “signs of change.” Therefore, it was considered that in support of military actions and according to Figure 1, hybrid warfare could use, in combination, a multitude of violent or non-violent forms, including media campaigns (propaganda), economic coercion, cyber-attacks and corruption (Ionita, 2018, pp. 230–234).

One important deduction from this assessment is that this new type of warfare did not exclude the transition to a more violent, conventional form, if the last phase (coercive) did not achieve its expected effects or it could create the optimal conditions for an escalation of violence. After evaluating the existing data related to those hybrid actions carried out by Russia in Ukraine after 2014 and extrapolating them to Europe, we can conclude that the first three phases were completed by Russia taking over the Crimean Peninsula and the direct military support provided to the pro-Russian separatists in the Donbass region. The last phase was also conducted in 2021, including the deterrence, new force posture2 and the shaping of Ukraine for the start of the invasion. A hybrid strategy was also used by Moscow in the Sea of Azov to build the biggest bridge in Europe and deny Kiev access to the area through frequently undertaken measures to board and control commercial ships transiting the strait to and from the Ukrainian port cities of Berdyansk and Mariupol, the navigation of military and commercial ships with a height greater than the bridge arch was banned, and the Sea of Azov began to be unilaterally exploited for water desalination, thus violating the 2003 Russian–Ukrainian Agreement (Kabanenko, 2021).

The restart of the Russia-Ukraine war as a continuation of Moscow’s Geopolitics to reestablish its Areas of Influence, which were lost at the end of the Cold War, represents another important deduction of this assessment. The return to “Power Politics” by using a high intensity and violent conflict also demonstrates that the current conventional war represents, in fact, a continuation of Russian Hybrid Warfare, with escalatory steps being taken against Europe. It was prepared and rehearsed in Georgia, in 2008, as well as in Ukraine, in 2014, and amplified by the Kremlin’s decision to militarily interfere in Libya and Syria, as well as in Kosovo.

Russia and Ukraine’s Conventional Operations

Russian President, Vladimir Putin, launched the “Special Military Operation” against Ukraine early in the morning of 24 February 2022, with the aim of achieving his political objectives through a more direct approach, in a single decisive operation conducted by combined arms formations over a relatively short period. This conventional approach was, in fact, a land-heavy offensive operation conducted in two phases—Phase I between 24 February and 18 April, and Phase II from 18 April to the present day. Initially, the Russian offensive was conducted in four operational directions (North, North-East, East and South), with eight Operational Groups organised in 168 BTGs, with a total of approximately 145,000 troops (Butusov, 2022). Russian troops were augmented by pro-Russian separatist militias from the Donbass region, organised in two Combined Arms Army Corps under the operational control (OPCON) of the Russian 8th Combined Arms Army Commander (The Institute for Strategic Studies, 2022, p. 215) as well as paramilitary fighters of the Wagner Group and up to 16,000 foreign mercenaries3 from the Caucasus and the Middle East. There are American, British and Ukrainian experts who consider that those thousands of foreign mercenaries were hired by Yevgheni Prigozin (nicknamed “Putin’s chef”), the head of the Wagner Group and 80% of the Russian paramilitary have been drawn from prisons, as well (BBC, 2023). According to the UK Ministry of Defence, “Wagner almost certainly now commands 50,000 fighters in Ukraine […] from a glossy HQ in St. Petersburg […] and has become a key component of the Ukraine campaign” (Goldie, 2023).

In mid-March, Russia’s main effort shifted towards East and South to increase the support of Donbass separatists and deny Ukraine access to the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. Meanwhile, in an attempt at diplomacy, some political negotiations at the level of Presidential representatives and Ministries of Foreign Affairs took place. At the end of this phase, no diplomatic discussions were successful. At the political level, Vladimir Putin announced that local referendums would be carried out in the already occupied Kherson region (Colectiv CSSAS, 2022, pp. 3–4). This shift of the main Russian effort also continued during Phase II, with a change in tactics used to achieve political objectives. In this respect, the offensive approach was changed from BTG-type actions to a “Scorched-Earth” Strategy4, conducted at the brigade level. The main Russian objective was to occupy and secure the Donbass region, including securing a logistics corridor between there and the Crimean Peninsula. The South operational direction became a secondary effort to block Ukrainian harbours on the Black Sea and control the southern part of Ukraine and to connect Transnistria as well (Sky News, 2022). The Russian Strategic Centre of Gravity (CoG) was also refined in reaction with the Western military support for Kiev—starting in mid-April, Moscow prepared a massive information campaign to denigrate the military foreign support given to Ukraine and moved on to hit key targets that ensured the external supply of the enemy (Republic World, Digital Desk, 2022).

As well as the large number of Ukrainian soldiers, their efficiency, and the local population’s resistence, the slow pace of the Russian offensive was exacerbated by the heterogeneity of their troops—mixing military soldiers with insurgent militias, including paramilitary fighters of the Wagner Group and Chechen irregulars. This is why, following the bold Ukrainian counterattacks in the North in mid-May, the Kremlin decided to withdraw its Northern forces from the Kharkov region and go back across the Russian border. In turn, this forced the President of Belarus, Aleksandr Lukashenko, to deploy some BTGs near the respective border and form a Southern Military Command to keep Ukrainian forces in place (The Public’s Radio, 2022). Another withdrawal took place in October-November in the Kherson region (in the south of Ukraine), where Russian forces gave up the Western bank of the Dnieper River. From a political perspective, President Putin enhanced the local administration and exercised control over all conquered Ukrainian cities by organising the so-called “vote of shame” in the four controlled regions—Luhansk, Donetsk, Southern Kherson and Zaporizhzhia—increasing the freedom of access for residents of those regions to travel to Russia (Express Web Desk, 2022). He also ordered the partial mobilisation of 300,000 experienced reservists, called “mobiki” and increased industrial production related to defence in Russia itself (Euronews with AP, 2022).

At the beginning of 2023, the Kremlin again changed the aim of its “Special Military Operation” from ensuring the guaranteed protection of Russia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity to a more popular and conventional defence against a hostile West and the unipolar world. The freshly nominated Theatre Commander in Ukraine, Gen. Valeri Gherasimov, just mentioned that his new objectives were to promote some military reforms to prevent a possible NATO enlargement to the East and counter the so-called “Collective West” (Lupescu, 2023).

The roles of the other Russian military services were to support the main Land offensive operation by neutralising critical military and civil infrastructure—such as airports, ports, air defence facilities, and energy systems—while conducting adjacent independent air and naval operations to gain Air Superiority in Ukrainian airspace, as well as Command of the Sea in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. One first “naval success” was considered to be the occupation of Snake Island, a strategic check point in the North-Western Black Sea, (Macias, 2022) and another the military blockade of the Sea of Azov and the commercial blockade of the Black Sea.

Since the beginning of the Russian invasion, the Ukrainian Armed Forces have used the so-called “porcupine defence” asymmetric tactics,5 combined with striking strategic objects in temporarily occupied territories and even in Russia using drones, long-range artillery and resistance-type actions. The Ukrainian “Autumn Counter-Offensive” represents a masterpiece of a conventional offensive operation, combining the art of dissimulation with Military Art. It was sequentially launched at the beginning of September, in two operational directions—North-East and South. Its aim was to liberate temporarily occupied territories using an indirect approach by systematically grinding down Russian troops and their logistics. Using a massive disinformation campaign, Kiev initially launched several counter-attacks in the South (Kherson region) to attract more Russian troops from the North, by convincing the Kremlin that this was the main counter-offensive effort. After two weeks, the real main counter-offensive was launched in the North-East to liberate the Kharkov region. Simultaneously, the Southern counter-attacks increased in strength and frequency, being transformed into a secondary counter-offensive direction to liberate the Kherson region. At the end of the year, Ukrainian offensive actions achieved their established objectives and Russian troops withdrew behind the border in the North and North-East and on the Eastern bank of the Dnieper River in the South (Gazdo and Arwa, 2022).

Despite several Russian and Ukrainian attacks in the Donbass region, the general situation at the time of writing is none of stalemate. Recent actions have been to improve current defensive positions and for Russian troops to fortify the Crimean Peninsula, as well as to refresh stocks and personnel in the case of both belligerents, in order to resume offensive actions.

Hybrid Actions Undertaken by the Kremlin

Since the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Kremlin’s conventional operations have been supported by hybrid actions, amplified by the nuclear threat, according to General Gherasimov’s “active defence” doctrine of 2019. In this respect, one of Moscow’s official statements about the Russian intervention in Ukraine was triggered by increasing the fights in the Donbass separatist region, starting on 17 February 2022, as a result of Kiev’s intention to defeat the separatist resistance in the area, and was supported by cyber and informational attacks, and by the exploitation, amplification and even the triggering of energy, humanitarian and food crises.

In this respect, Russia’s “Special Military Operation” was preceded by some cyber-attacks focused on the Ukrainian governmental administration and financial systems, in order to neutralise/limit its ability to react and delay the mobilisation of its forces. The attacks used eight different types of phishing software, blocking critical services and certain government sites (Lewis, 2022). Even if Russia does not officially hold cyber-attack capabilities, the activity in this operational domain was all sporadically carried out by the so-called “independent hackers”/groups of hackers financed by different Russian security institutions. These hackers/group of hackers launched more than 2,000 such attacks, most of them were only in support of Cyber Intelligence and fewer in support of the Russian Army’s effort (Bateman, 2022). This was because the Kremlin considers cyber-attacks as enabling activities and not ways to achieve strategic effects. This was also the case in the “KilNet” cyber-attack at the beginning of 2023, directed against some German administration websites, including banks, state companies and airports, because of Berlin’s decision to send modern battle tanks to Ukraine.

Triggering a major energy crisis in Eurasia through specific Energy Warfare is considered by Moscow a very dangerous but efficient hybrid action. Energy Warfare took place against both Ukrainian authorities and population as well as some neighbouring states and even Europe. We can say that hybrid energy actions gradually increased and compounded the disaster and the humanitarian catastrophe throughout the entire territory of Ukraine and some of its neighbours by hitting civil residential areas and the most important critical infrastructure. The Russian “Dark Skies” Air Operations6 are considered part of the hybrid strategic Line of Effort to neutralise/destroy Ukraine’s energy economy and infrastructure in support of the conventional Line of Military Effort. It includes strategic targets of the Ukrainian energy system with the aim of destroying/neutralising up to 50% of Ukrainian electric plants, which, in turn, has produced wide power shortages throughout the country, leaving the capital and other big cities without electricity (Ellyatt and Macias, 2023)

Another hybrid action to amplify an already existing crisis in Eurasia is the humanitarian one, which exacerbated the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and illegal migration from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) to Europe in previous years. In 2022, over 15.7 million Ukrainians became refugees and moved to neighbouring countries, many of them entering through Poland, and almost 5 million of them requested temporary residency status in Western European countries (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR], 2023). Almost 3.9 million Russian and pro-Russian Ukrainian citizens were not taken into account in these figures, because of their partial mobilisation or fleeing from conflict areas in Russia.7

Of similar significance was the triggering by Moscow of a food crisis at regional and global level, which mainly concerned Africa and the Middle East. After the naval blockade that resulted from the invasion, in which neutral commercial vessels were caught up, the international community and, in particular, Türkiye and the UN, managed to convince Russia and Ukraine to conclude an agreement called the “Black Sea Grain Initiative (BSGI)” in July 2022. Through the BSGI, ships loaded with grain were allowed to navigate from three Ukrainian ports towards the Mediterranean Sea. But, even if more than 690 commercial vessels managed to cross the Türkiyesh Straits, carrying about 19.2 million tons of grain, numerous delays have been caused by theRussian authorities, byfrequently inspecting and not allowing the respective ships to depart (Ellyatt and Macias, 2023). Furthermore, at the beginning of November 2022, Russia even blocked the respective initiative in response to Ukrainian drone attacks on Russian battleships stationed in Sevastopol harbour.

The Geopolitics of the Extended Black Sea Area was very complicated even before recent events in Ukraine. We can speak of the persistent “frozen conflicts” in the region, especially in Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Transnistria, where some activities endangering the security of the region have taken place. The most obvious example is Transnistria, the Moscow-backed separatist region of Republic of Moldova, where, up to the beginning of 2023, Chisinau has been the victim of a complex hybrid action carried out by the Kremlin on multiple levels. In this respect, the Transnistria region has long been used by Russia as a bargaining chip in its efforts to influence Republic of Moldova. It is also worth mentioning the Kosovo crisis and the military support provided by Moscow to Belgrade,8 and also the recent spate of bomb threats and cyber-attacks in North Macedonia and Serbia as part of the most recent Russian campaign and the change in the Russian-Serbian psychological disinformation strategy in the Western Balkans. But such attacks have also been reported in New Zealand, the USA, Canada and Germany, representing a real hybrid war against some NATO Members and Partners.

Through all the hybrid actions undertaken throughout 2022 and early 2023, which were heavily supported by escalating nuclear deterrence measures, Vladimir Putin aimed to reduce Western support for Ukraine and weaken the cohesion of NATO and the EU. Moscow has repeatedly tried to break the transatlantic link between the US and its European allies, believing that without support and coordination from Washington, Europe will stop providing economic and military support to Kiev and will weaken the sanctions imposed on Moscow.

Lessons identified and their consequences for European Member States

The Russian invasion of Ukraine can be considered a real “strange war,” in which one can hardly speak of the application of the 2019 “active defence” doctrine of General Gerasimov. Instead, we can consider it a continuation of the 2014 Russian “hybrid warfare,” being transformed into a purely conventional high-intensity conflict to fulfil the Kremlin’s power politics’ ambitions. In addition, the entire military action carried out by the Russian Army after 24 February 2022 could be characterised as a Second World War-type of operation and not a conflict of the 21st century. As a whole, the Russian “Special Military Operation” has neither achieved the “blitzkrieg” effect nor demonstrated a real “tank-airplane binomial” action to rapidly obtain victory for Moscow.

This chapter presents, clearly and concisely, the results of scientific research conducted in the previous one regarding what has been happening in Ukraine since February 2022 in the military domain, both conventionally and hybrid. Using the analytical method of research and the lessons identified, we formulate possible implications for European and Euro-Atlantic security, and for European nations living at the edge of this conflict.

To maintain its influence in Eurasia, Russia repositioned itself as a great power by using the old “power politics” approach, practically initiating the largest number of military conflicts in the South-Eastern part of Europe and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) since the end of the Cold War. In its endeavours, Moscow considered retaking control of the Black Sea Extended Area (BSEA) as paramount for its national interests, especially after the illegal annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014, by continuous use of “frozen conflicts” as a diplomatic weapon and the illegal, unprovoked, brutal invasion of Ukraine that upended many aspects of European security. In this respect, riverine nations like Romania, Bulgaria, Republic of Moldova, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and some former Yugoslav republics, felt exposed to a lot of security risks and having a lack regional solutions to mitigate them.

Being considered a land-centric country, Russia knows very well how to use its surrounding waters (the Northern Sea, the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea, and the Mediterranean Sea through proxy) to protect its territories and intimidate the West. As an example, Moscow uses the Black Sea without any restrictions as a platform to obstruct freedom of navigation, increase tensions in the region, maintain “frozen conflicts”, and create favourable conditions for transnational security threats. All Russia’s main goals are to maintain instability and influence the free will of regional partners in choosing their future, as well as to use the Black Sea as logistics support to send forces to the Mediterranean and the Middle East. (Allied Command for Transfromation, 2023) This belligerent behaviour exacerbates security risks for riverine Allied nations and keeps this region volatile and unstable for European and Euro-Atlantic security as a whole. This is why both NATO and EU should develop a very robust and comprehensive Black Sea Security Strategy.

More than a year after the start of Russia’s “Special Military Operation” in Ukraine, there is no possibility of a ceasefire or to conclude any serious negotiations for a peace agreement. This is very true because the divergent national interests of the great powers has ensured that what happened in Ukraine cross the European continent and become a global problem in which the current world order is at stake (VOA News, 2022), and the outcome of the war is still inconclusive and may continue for the longer term. For NATO, the EU and their member states, it becomes of greater importance to maintain the leadership of the US, in order to face a currently divided World between the West (including here the US, the EU, NATO, and G5) and the growing number of BRICS9 nations (including here the Shanghai Cooperation Initiative, CSTO, and G20). In this divided World, a new Cold War-like scenario appears as more and more realistic, in which a probable “Iron Curtain” could again descend at the edge of Europe and Asia, as shown in Figure 2. On one side will be the US-West block, including new allies such as Finland and, in the near future, Sweden or countries with a European perspective (like the South Caucasus ones). On the other side will be the BRICS block countries, including here the ones that remain within Russia’s sphere of influence (Belarus and Republic of Moldova). Türkiye will be in a difficult position if Ankara considers itself as more of an Asian country. In this scenario, Ukraine will lose its eastern and south-eastern territories and will become like the divided Germany of the 1960s–1980s, having the Dnipro River as its border. The status of Armenia remains unclear.

Despite the negative effect of divergent regional powers and national interests in Ukraine, the importance of international support being provided to one belligerent in such a demanding war of attrition/prolonged conventional war has been positively demonstrated. The biblical “Goliath versus David fight” that can be used to describe the beginning of the Russian invasion in Ukraine was supposed to finish very quickly in Moscow’s favour, without NATO and the EU member states indirect involvement in support of Kiev, both economically and militarily. The modern Western high-tech military equipment demonstrated very soon that a future conflict could be won by new technology and new ways of using old tactics in the modern battle space. A big role in military capabilities superiority was played by Western advisers and instructors who succeeded in training Ukrainian troops quickly to efficiently use modern weapon systems. In the end, it seems that this war could be won by the side that can better sustain the huge logistics consumptions and improve its defence industry production capacity, as well as by faster regenerating its human resources. In order to fulfil the first requirement, it is important to maintain strong and permanent international support. For the second, a whole-of-nation approach is mandatory, but not enough. Sometime, it also requires additional foreign fighters to be enablers for active and reserve forces.

Of no lesser importance was the morale of troops and population for both parties involved in the conflict. On one hand, the strong physical and moral support provided by the local population to Ukrainian forces was crucial for maintaining troop morale and increasing national resilience too. It was not the simple support provided, but the direct involvement of the local population in the conflict as a new actor and the maintenance of the whole-of-nation will to fight.10 Therefore, local civilians suddenly became members of the Ukrainian resistance and conducted a guerrilla-type of warfare and multiple “hit-and-run” tactics, continuing to provide support to their own soldiers.

On the other hand, the Russian troops and the population’s morale were not well sustained by efficient Russian propaganda, because the focus was against the Information Warfare from the West and not in support of its own troops. Fighting in a former Soviet territory and against former brothers did not encourage Russians soldiers too much. Their poor training and mixing the military with insurgents from the Donbass region, the paramilitary forces of the Wagner Group, and foreign mercenaries did not support the morale or the homogeneity of Russian fighting units. Vladimir Putin’s announcement of partial mobilisation in September 2022, followed by amendments to Russia’s law on military service (which increased the penalties for resistance related to military service or violating an official military order during a period of mobilisation or martial law) neither eased the Russian soldiers’ situation on the battlefield, nor improved their morale (McCarthy and Picheta, 2022). At the same time, the new threat of enrolment for war saw some Russians revolting against the threat of military call up to the Ukrainian front, and some leave Russia altogether and escape to Finland and some of the Caucasus states (Ritter, 2022). The internal protests and the exodus of some Russian civilians beyond the country’s borders have created the idea that partial mobilisation is a risk and not an enabler for increasing fighting power.

Unfortunately, for Eastern European Allies like Romania, Bulgaria, Poland, the Baltic States and the Czech Republic, Russia’s “Special Military Operation” has proved that a former risk can quickly become a real threat to their national security. This has been exacerbated Vladimir Putin’s multiple warnings to the populations of those countries and the Russian military presence near their borders. The socio-economic situation there has also been threatened by the huge waves of Ukrainian refugees transiting or asking for asylum, as well as by the transit and competition of Ukrainian agricultural products inside their internal markets. The risk of prioritising transport vehicles for Ukrainian products ahead of internal requirements, and the cheaper non-EU agricultural products with limited pest control has added to the economic crisis in the region.

Eastern European Allies, together with NATO and the EU, are therefore very interested in a swift resolution to the conflict situation in Ukraine and not letting it spread to neighbouring countries such as Moldova, in order to mitigate or diminish the effects of the ongoing crises in Europe and around the world, including in the fields of energy, economic-financial, humanitarian and food. The new NATO Strategic Concept, together with the Allied extended Forward Presence (eFP) and the new enhanced deterrence and defence posture (DDA), based on a 360° approach, represents a strong NATO commitment on the Eastern European flank to protect the populations and defend every inch of Allied territory at all times. These measures, unprecedented in NATO’s history, are aimed at ensuring that Eastern Europe does not wake up with a new Cold War on its doorstep, this time with the “wall” on the Prut River.

Conclusions

We have firmly concluded that the conflict itself has deepened the international consequences of almost 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has led not only to an international health crisis, but also to economic, financial and social ones. It has magnified the disastrous security situation not only in Europe, but around the world, by creating additional energy (gas) and food (cereal) crises. In turn, the food crisis has been and continues to be heavily amplified by some of the consequences of climate change, including drought and heat waves that have hit Europe, North America, and Africa. Therefore, the Russian—Ukrainian War has significantly modified the regional and international security environment and the current world order is being challenged. In fact, the current regional situation is very similar to that of Europe at the end of the Cold War.

The scenario with the division of the international community into two antagonistic political blocks that point to a “bipolar world” and a possible new “Iron Curtain” between Europe and Asia, represents a theoretical test to determine whether the deductions and conclusions fit the formulating hypothesis and demonstrate the war’s possible implications for European and Euro-Atlantic security, and for European nations living at the edge of this conflict. The effects of what has happened and continues to take place in Ukraine is being felt beyond the borders of Europe and is having implications all around the world. There are already two established antagonistic political blocks that support different belligerents in Ukraine, without any official lead-power, but with regional power in a coordinating role. Currently, they are competitors which support one side or the other, but the situation in Eurasia is so fragile that it could immediately spark a Third World War. One block is represented by the US-Western democracies, including the member states of NATO, the EU, and G7, plus other democracies from around the world. A model was already established—the Ukraine Defence Contact Group (aka the Ramstein Group)—which comprises 54 countries. Unfortunately, the economic imbalance between the US and its European allies continues to increase and there is little chance for the EU to achieve its desired “strategic autonomy” in the near future. The second block represents an extension of BRICS with other member states of G20, which are fighting to establish their own Asia NATO, a new monetary reserve to compete with the US dollar and a possible common crypto currency.

The lessons identified in this paper related to the political-military field have and will continue to have geopolitical implications for Europe and the Euro-Atlantic area, with some national consequences as well. The soft diplomatic power of international and regional organisations with a security and defence role, like NATO and the UN, has not yet been effective to deter any regional power from starting violent action to fulfil its regional interests. Moreover, the military power of a state, whether a regional power or not, is not enough to obtain the desired strategic objectives on its own. Therefore, conventional operations should be supported by other types of operation, like unconventional and hybrid ones, enabled by nuclear deterrent measures, and political-military alliances/coalitions should be established during peacetime. At the same time, conventional operations could efficiently support state-sponsored hybrid warfare by destroying critical civilian infrastructure, training and counselling separatist militias and conducting maritime blockades.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is considered a “strange war” by numerous political and military analysts because it has used both conventional operations and hybrid warfare tactics, and has been amplified by the threat of using nuclear tactical weapons. If the conventional war was conducted only against Ukraine, the hybrid actions and nuclear threat statements were, from the beginning, addressed to Western capitals to diminish their economic and military support of Kiev and cancel the international sanctions against Moscow.

The hypothesis we formulated at the beginning of this article is demonstrated by the lessons identified from the first year of war, outlining their possible implications for regional and national security and providing some possible solutions for solving the regional situation and reinstating the status quo. The paper is limited by the fact that the war is still going on and there are many scenarios on how it could end. Another limitation is that neither this paper, nor even NATO has a Plan “B” to deal with a possible “Russia win the war” scenario and mitigate its consequences for European and Euro-Atlantic security. It is therefore necessary to continue this analytical method of research in order to firmly identify lessons for the military that could be implemented for the future security of Europe and the international environment. The final result of this further analysis should present possible solutions for mitigating the geopolitical implications for Europe and the Euro-Atlantic area, and some national consequences as well.