Introduction

The issue of security culture is becoming increasingly popular among both scientists and practitioners. One of the first combinations of the terms “culture” and “security” was made in English-language literature in the second half of the 20th century by N. F. Pidgeon. He believes that a culture of security is a system of meanings through which a specific group of people understands global threats, reveals their attitude to risk, threats and security, and what values they consider relevant in this regard (Pidgeon, 1991, pp. 129–130).

Security culture is studied in both theoretical and empirical aspects. The research method used to write the article included the classical theoretical method used in security sciences, based on analysis of literature and scientific articles with the use of synthesis, abstraction and generalisation. The study is a review of theories and published research about security culture and family. The overall goal of the article is to present the phenomenon of security culture. The specific goal is to analyse the possibilities of family influence on shaping security culture among children. The aim of the paper is to answer the following research questions: What is security culture, what elements make up its structure and what role does family play in shaping it?

Family – a fundamental social unit

In sociological terms, family is considered the fundamental social unit in which processes that create economic, demographic and cultural systems take place (Nowak, 2012, p. 4). Thinking about family, we usually consider it as the most important and best institution that has an influence over the future of every individual. Within families, which are an important element of the social network, each person is equipped with a specific way of thinking about security and the ability to perform actions that ensure security. The family is the foundation of society, the smallest unit of society and, therefore, critical to its development and maintenance (Enrique, Howk and Huitt, 2007). According to Matejek and Kucharczyk (2017, p. 121) “[i]n literature, many definitions of family can be found and they include a description of family as an institution, social group or child upbringing environment, because the term ‘family’ is common in all civilisational societies in all their forms and shapes. Family is a unique community of people, who live together and for each other. Right there, its members play many important roles and achieve goals in order to uphold the cultural and biological continuity; a family fulfils basic needs of humankind such as: love, self-realisation, and belonging, and ensures a sense of security for all its members”. As well as the synthetic explanations included, there are other more or less detailed views in the literature regarding the interpretation of family issues and different ways of analysing phenomena occurring in a family. For example, looking at the integration of knowledge about family from the sociological point of view, Bieszczad (2005, p. 6) explains that he particularly appreciates sources of multidisciplinary knowledge in the field of family studies. On the other hand, Nowak (2012, p. 3) explains that family is understood differently. It depends on the worldview or the discipline of science and an adopted definitional core. Psychologists pay attention to the system of emotional ties that defines the community-based nature of family. Lawyers recognise it in formal and legal terms. Pedagogues analyse family through the prism of its functions for human development, while sociologists emphasise the importance of a set of roles and positions of family members. As it was noted by Tomás (2013, p. 174), “there are, therefore, different concepts of and approaches to family, each having a different operationalisation. They are also influenced by the available research resources, especially available data.” However, each of the approaches to the issue of family indicates its great value in human life.

Views on the irreplaceable role of family in the educational process are not, however, fully accepted everywhere and by everyone. According to James S. Coleman, “families at all economic levels are becoming increasingly ill-equipped to provide the setting that schools are designed to complement and augment in preparing the next generation” (Coleman, 1987, p. 32). It is worth mentioning that in other publications, it is hard to find support for such theses. Most views are opposite and present family as the foundation of every society, the only and the best place for human development and entering into the world of culture of a given society (Ziemska, 1977, p. 5). Naturally, it should be noted that family is not the only social unit influencing its members. Families function in a network of social relations and dependencies, creating a gigantic, structural collection, cemented by social and legal norms, traditions, customs and human duties (Nowak, 2012, p. IX). Various kinds of media, school, other institutions, peers and the whole of the surrounding environment have a very strong influence on people today, especially the young. The significance of innate traits that determine one’s own activity should not be omitted either. Individual qualities as well as the institution of family may, to a greater or lesser extent, work in favour of or adversely affect the development of family members, including children. Research on mutual socialisation between parents and children confirms the thesis that being a parent affects both the development of adults and the children. According to Wilson and Gottman (2002, p. 252), “when couples are unable to use repair mechanisms effectively to resolve conflict and repair negativity, their marriages and children suffer. Specifically, unresolved and chronic conflict and negativity in marriages steal emotional energy from important parental roles, such as being providers and facilitators of children’s social opportunities. It undermines the ability of parents to support each other’s parenting and spills over into the parent–child setting, particularly corroding positive affect and increasing irritability”.

In the family life cycle, seven stages can be distinguished (Liberska, 2003, pp. 68–74). In the first, the marital stage, the married couple learn their roles. Their mutual relations usually bring a lot of satisfaction. The second stage, called the parent stage with a young child, is the time in which the spouses, without giving up marital roles, fulfil new ones - they become parents. Such a situation is very beneficial not only for the development of a child but the parents as well. It is plausible that such development concerns opportunities and ways of caring for security or even security culture. According to John Paul II (1994), “the man and the woman must assume together, before themselves and before others, the responsibility for the new life which they have brought into existence.” Already at this stage, consciously applied realisation of the assumptions of security culture may affect a child’s safety throughout his or her whole life, as well as his or her inner sense of security. During the third stage called the parent stage with a child in the school age, the married couple concentrates on activities that make it easier for a child to enter the school’s and peers’ environment as well as participating in the process of starting the child’s education (Liberska, 2003, p. 70). During this period, tasks related to family life undertaken in the previous stage are continued. The fourth phase is called the parental phase with a child during adolescence. This is a hard time, a time of special concentration on the problems of children. From the point of view of the parents, the most important moment in the realisation of the developmental task takes place in this period. This is accompanying children in dealing with the difficulties of adolescence and entering adulthood, and several other developmental tasks such as stabilisation of the level of material life, the acceptance of one’s own biological changes and providing help for ageing parents (Liberska, 2003, pp. 70–71). However, it should be noted that this specific stage is not always filled with the same difficulties. It is plausible that a certain level of difficulty in this phase is influenced by previous ways developmental tasks were carried out. In the next, the fifth stage of the family’s life cycle when one child has already become independent and others grow up, the spouses have more time for themselves and the atmosphere of home life is often better than the fourth – the crisis stage. The sixth stage is called the secondary marriage and concerns the spouses whose children have become independent. At this stage, the spouses take on new roles – grandparents. The seventh – the last stage, called marital – retiree, is the time when spouses focus on their own health and financial problems related to running a household. A characteristic feature of marriages during this period is the idealistic attitude to marriage, similar to the first phase of the family’s life cycle. All the distinguished stages of family life are strongly associated with the stages of children‘s life. It is not surprising since, as was noted by Bongaarts (2001, p. 263), “the principal social function of the family is to bring children into the world and to care for them until they can support themselves.”

A properly functioning (healthy) family is a psychosocial system that in the view of Siamak (2011, p. 2288), “has a high efficacy for rearing children, establishing good communication, coping with stressful situations, solving problems, satisfying each other, […] making decisions and so on.” The indicated elements concerning the assessment of a family’s functioning are also helpful to focus on the possibilities of diagnosing a family’s security culture. Such an issue should not be considered as irrelevant or marginal, since it concerns one of the basic human needs – the need of security (Taormina and Gao, 2013, p. 157). Security is a prerequisite for other needs, such as the needs of belonging, recognition and self-fulfilment. The understanding and the interpretation of the term “security” largely affects how security is achieved on a daily basis, and is one of the manifestations of security culture. Each person autonomously, under the influence of experiences and personal observations, strives to satisfy the need of security in his or her own way. These may not be the most favorable solutions to the emerging situations and the consequences of such activities are varied. Sometimes, we do not know that it is possible to act differently, or that another concept of functioning would be more favourable. Patterns that concern specific methods of achieving desired goals, usually aimed at achieving security, are learned and solidified in a family home and are most often reproduced, without reflection, in successive generations. Therefore, security culture can be the carrier of such content that in the most favourable ways will support shaping the security of a given person and his or her environment. The basic characteristic of manifestations and determinants of security culture is presented in the next part of the paper.

Security culture and the possibilities for shaping it in the family

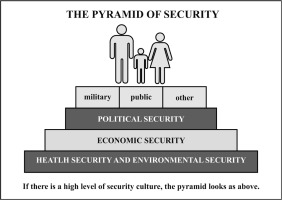

In order to explain the meaning of “security culture”, which is the basis for reflections on the role of family in shaping it, it is worth using Cieślarczyk’s (2009, p. 157) interpretations of this concept who claims that“security culture is – to put it very simply – a way of thinking about security and sensing security, as well as methods of achieving security characteristic for a given entity.” Such an approach indicates that our behaviour that is aimed at achieving security is justified in thought projects regarding this issue. In the view of Piwowarski (2018, p. 26), “[s]ecurity culture is all the material and nonmaterial elements of the embedded legacy of people, aimed at cultivating, recovering (if lost) and raising the level of safety of specified active persons or entities. It can be considered in terms of individual – mental and spiritual, social and physical dimensions” (Piwowarski, 2018, p. 26). It is worth mentioning that security culture can be treated as a component of human personality which affects knowledge and skills in the area of shaping one’s own and the environment’s security, currently and in the future (Ziemska, 1977, p. 11). The basic issues of security culture are values recognised and accepted by a given person (Figure 1). They are the pillar of security culture. Budnyk and Mazur provide a definition of values and claim that “as values we consider everything that is particularly meaningful and important for us in terms of our objectives, interests, needs, communication etc. Values is therefore a subjective category, because things that are valuable for one person may be completely insignificant for another” (Budnyk and Mazur, 2017, p. 54). Dağ and Cinar point out that “values encompass development of ethical, cultural, spiritual and social sensitivity and internalisation of these values. Social and humanistic values are vital components of human life. Sympathy, affection, courage, friendship, cooperation, respect, honesty, courtesy, hygiene and many other things are greatly esteemed social values. Individuals manifest these values in their actions and, in turn, receive respect and approval from society. Values are not only significant in terms of the principles and standards governing our daily actions and behaviour. They are equally important in how they affect and determine the direction of our lives” (Dağ and Cinar, 2015, p. 1). Figure 1 shows the location of values at the centre of the security culture model.

Fig. 1

The entity and its elements of security culture in the ideal model (Cieślarczyk, 2009, p. 160)

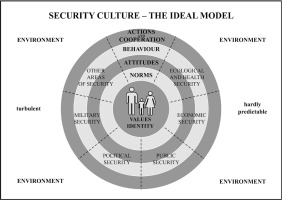

Situations encountered on a daily basis that have their sources in various areas of security are usually assessed through the prism of a certain hierarchy of values. It is also worth noting that Picture 1 also contains several sectors corresponding to the areas of security. Referring to the interpretation of this issue, in the ideal model, each sector is of similar size, which means that a given entity presents a similar interest and care for each of the security areas in everyday life (Filipek, 2016, pp. 78–79). Such an approach makes the entity prepared to deal with different types of challenges, opportunities and threats and with different risks occurring in each of these areas of life, in each of the security sectors (Cieślarczyk et al., 2014, pp. 24–25). Taking into account the nature of the security culture of a given entity, it is extremely important to use accepted values as a basis for creating a hierarchy of life situations derived from the areas of security and to respect this system in everyday behaviour, actions and cooperation. Value systems have a hierarchical structure and, as was noted by Haynes and Hickel (2016, p. 2), “hierarchy draws our attention to the way that values are organised with respect to each other, since values are hierarchically ranked, with some being more important than others. Hierarchy is therefore a central component of any theory of value.” According to the pyramid model of security, a high level of security culture should lead to the hierarchy of particular areas of security, which is similar to the one shown in Figure 2.

When analysing the ideal model of security culture (Figure 1), it can be seen that values should be the basis for constructing norms. If these norms continue to be followed by specific attitudes and then aby the actions and cooperation of people, it can be assumed that it will lead to achieving a higher level of broadly and positively understood security. Norms derive from values and, as was noted by Pereira, Baranauskas and Liu (2015, p. 33), “if values serve as standards to guide action, judgment, argument, evaluation, and choice, then they may act as a specific kind of force that make the members of a community tend to behave or think in a certain way.”

According to Roostin (2018, p. 1), “family environment is the first educational environment, because in this family, every individual or child first receives education and guidance. It is said that in the main environment, because most of the life of an individual or child is in the family, education is most widely accepted by the child in the family and family also provides basic knowledge of ethics and norms.” The cited observations lead to a conclusion that the place where every young person is introduced into the world of security culture is primarily the family home. In the opinion of Adamczyk (2014, p. 265), family is a kind of bridge connecting an individual with society, which helps gentle engagement in the life of the social group. The way a family functions determines how an individual enters society. It depends on the manner in which a child learns and internalises the social values and customs adopted in a given society and to what extent he or she has learned to apply patterns of conduct and action in recognised environments. It should be added that even if a person does not realise the existence of the phenomenon of security culture, it affects their behaviour since the perception of security and the pursuit of security exists in human nature. A family home is a place where everyone, from an early age, observes how parents and other people from the close environment pursue their own ways of achieving security. We usually repeat them because we do not know how else to proceed.

It should also be noted that the specific reactions and ways of proceeding adopted and recorded in a family home are very deeply coded and stored in a memory, especially in the memory of young children. Using the assumptions of Erikson’s theory, Grzelak (2004, p. 22) explains that the earlier stage in human development, the more important it is. Human development is as a tower made of blocks. If we remove the lower block, the bigger part of the tower collapses. If the lower brick is deformed, the bigger part of a personality has a fragile basis. The author also points out invisible foundations. He notices that the memory of an adult reaches back no further than to the age of about 3 years. What went before is like a foundation buried in the ground and, although invisible, it is the basis for everything. For a favourable, strong foundation, positive effects can be foreseen in the long term and at least satisfactory results in the pursuit of security may then be expected.

It is much more difficult to pursue security for people who were brought up in a family home in which security culture had an unfavourable nature and was at a low level (Filipek, 2008, p. 35).

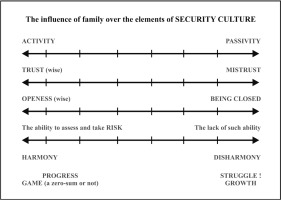

In addition to the above-mentioned fundamental aspects of security culture, its detailed elements are extremely important in relation to their impact on a personality, especially the personality of a young child (Figure 3).

Fig. 3

The influence of family over the elements of security culture (Cieślarczyk, Filipek, 2013, p. 284)

Figure 3 shows scales, at the borders of which there are opposite possibilities of functioning in the area of detailed elements of security culture. The first element is activity or a lack of i.e. passivity. It is obvious that the ability to contribute and influence the surrounding reality through one’s own commitment and willingness to demonstrate knowledge and skills is a much more beneficial way of functioning. Imitating adult behaviour is the easiest method for following the assumptions of activity. It may also be beneficial to present one’s own initiatives as valuable. On the other hand, excessive criticism towards a child’s intentions may forever discourage him or her from being active, which, in turn, may bring about a reduced sense of security and affect its actual level.

Another essential feature of security culture is the aspect of trust, which is an important factor influencing the ability to take a risk. Giddens (2002, p. 6) explains that the level of trust established between a child and its keepers is “a vaccine”. It protects the child against potential hazards to which an individual is exposed during daily activities. The bond between a child and a parent or parents created on the basis of trust is probably the foundation for the ability to build social relationships in the future, especially in terms of taking risk.

Risk can have various meanings and, according to Hillson (2001), it “is an umbrella term, with two varieties: opportunity, which is a risk with positive effects, and threat, which is a risk with negative effects.” However, the attitude towards risk and the perception of risks is changing. Nowadays, risk is more and more often considered as a positive aspect which means that attention is paid to occurring opportunities to achieve success (Redziak, 2015, p. 17). It is hard to disagree with Renn (2008, p. 50) who claims that “all concepts of risk have one precondition: the contingency of human actions. At any time, an individual, an organisation or society as a whole faces several options for taking action (including doing nothing), each of which is associated with potential positive or negative consequences. Thinking about risks helps people to select the one option that promises more benefit than harm compared to all other options.” According to Kahneman (2013, p. 164), “risk does not exist ‘out there,’ independent of our minds and culture, waiting to be measured. Human beings have invented the concept of risk to help them understand and cope with the [...] uncertainties of life.” There is no change without risk and if there is no change, there is no progress, no development and, therefore, no security (Filipek, 2008, pp. 141–148). The literature provides theoretical determinants that concern the influence of cultural factors over the attitude of being ready to take risks or resigning from such actions. The way of perceiving and understanding the emerging threats is conditioned by internalised collective beliefs that are characteristic for individual educational environments, which are culturally influenced. Giddens (2002, p. 109) also states that by forcing us to use modernity, the current world exposes us to risks and dangers that have always been associated with human history. He explains that risk is usually associated with the chance of development, which is the condition for security. The aforementioned author also takes the view that true security does not come from the outside but from the inside and, in order to feel really secure, we must trust ourselves completely. It can be assumed that this type of skill has foundations that should be shaped in the family starting from the earliest years of a child’s life. Such a manner of preparing for adult life can lead to acquisition and consolidation of skill patterns, contributing to a high level of security culture in everyday situations, which is likely to be reflected in more comprehensive security in general.

Describing the issue of trust or distrust, Sztopmka (2002, p. 313) notices that if the activity of a given entity is dominated by optimism and hope in relation to the behaviour of various entities, we are dealing with the culture of trust of this entity. If distrust and suspicion dominate, there is a culture of distrust. It is most advantageous for a given individual to be wise in trusting and distrusting. One should therefore be guided by rational arguments in relation to declared and represented attitudes. A more favourable situation for a society is undoubtedly the functioning of the culture of trust in its consciousness, rather than the culture of distrust, since the culture of trust leads to openness, cooperation and innovative activities. As was noted by Smetana (2010, p. 223), “developing an appropriate balance of trust versus mistrust in early childhood is one of the normative crises that must be resolved during the lifespan and is central to how later developmental crises, especially the development of identity in adolescence, are resolved.”

Trust and willingness to take risks are both closely connected with the openness of a person. People who put trust in others are most often open, direct and straightforward. On the other hand, those who are secretive, closed and inaccessible are more likely to be distrustful. When analysing the issue of openness, it is worth noting that it should not be manifested in absorbing all novelties, all precursory symptoms and signals coming from various directions. Wisdom should be the basis in these matters. The notion of wisdom has already been interpreted in relation to its connection with security culture (Cieślarczyk and Filipek, 2011, pp. 156–158). Pietrasiński (2001, pp. 74, 77) believes that the manifestation of high general cognitive culture is to look at a given issue from many perspectives. Wisdom is willingness to look from different perspectives, a skill in looking from many perspectives and an effect of looking from many perspectives. There is a slight difference between wisdom and intelligence. According to Sternberg (2001, p. 231), “wisdom is a kind of practical intelligence (…), but it is not just any kind of practical intelligence. Wisdom is not simply about maximising one’s own or someone else’s self-interest, but about balancing of various self-interests (intrapersonal) with the interests of others (interpersonal) and of other aspects of the context in which one lives (extra personal), such as one’s city or country or environment or even God.”

Therefore, everyone must always see a big picture while operating in a small one with seriousness and contentment. Nowadays, it is to some extent reflected in the saying: “think globally, act locally”. From the point of view of the mutual relationship between wisdom and security culture, the fact that a wise person gains recognition for the ability to look at a given matter from many perspectives seems particularly important. Such a person is able to thoroughly assess difficult situations, anticipate their effects and make accurate judgments in matters concerning life and conduct (Pietrasiński, 2001, p. 15). Security culture allows a multifaceted entirety of security to be discovered, because it takes into account all the dimensions of security, making it possible to deal with matters in a big picture. Intelligence is characterised by the desire to understand as many phenomena as possible, while the aspiration of wisdom is a deeper understanding (Pietrasiński, 2001, p. 87). To understand deeply is also to reach into cultural determinants of processes and phenomena for which the system of entities’ values and their identity is an important factor. These, in turn, constitute a specific core of the security culture of individuals and social groups, which is illustrated in Figure 1.

The current research on the phenomenon of security culture indicate that both its level and its character are shaped primarily in a family when a child is in preschool and of school age. In further stages of life, the inclinations in this area are usually fixed and reproduced. According to Adamczyk (2014, p. 265), family is a kind of bridge connecting the individual with society, which helps gentle engagement in the life of the social group. Such a conflict-free way of functioning in society can result from wise management of one’s own activity, openness, trust and risk.

Wise risking in adult life requires experience gained in early childhood and youth. The importance of courage is also essential. According to Vygotsky (1971, pp. 521, 543–544), the eminent Soviet psychologist, it is proven that for all procedures from the area of education and didactic the most significant are those traits of personality that have not yet matured. He also stated that teaching focused on the child’s developmental cycle that has already been completed is ineffective. Such an approach does not lead to development. According to Ogrodzińska (2004, p. 7), the first six years of life is the period of forming the foundations for future education. Dąbrowska (2004, p. 37) claims that a one and a half year old child needs to define where it is safe and establish security boundaries as well as freedom. She believes that it is necessary to let a child learn about the world. This will help a child to build his or her sense of self-confidence, which will pay off for years . The moment of being a perpetrator is one of the most crucial experiences in the child’s development. The feeling that a child has an impact on the situation happening around is the moment of building self-confidence, which will bear fruit in the future. It seems plausible that if the need for activity and arousing responsibility is not properly developed during childhood, the adult will lack the conviction that responsibility for our own security is on anybody else but us. It seems that the positive effects of children’s practical activities, resulting from their internal needs, concerning intrinsic courage specific for a child of a certain age are the source of the sense of self-confidence, courage, valour and boldness. It can take place, for example, in the case of climbing stairs or climbing a ladder in a playground. Allowing a child to overcome various difficulties and challenges, applied to its developmental stages, and with the protection of a responsible adult, is a difficult undertaking. However, if properly implemented, it can have a positive influence over shaping a high level of security of people and their environment (Filipek, 2017, pp. 11–23).

In the view of Drabik (2017, p. 77), the humanistic origin of security is based, among other things, on the beliefs that security arises from culture and, at the same time, creates culture. This is proven by intense development of security culture, which is one of the factors determining the dignified form of existence of entities. The aforementioned author also claims that security culture is every activity of people in both material and non-material aspects oriented towards creating a safe existence and defining development boundaries appropriate for this purpose. Security culture defines human activity in mental, rational and material areas that lead to meeting the need of security by facing challenges and achieving goals and interests in this field. Knowledge and skills in these areas are primarily acquired during family life, in everyday situations. Such experiences have the greatest impact on how we are likely to function in adult life. Therefore, it would be very disadvantageous for a child, but also for its environment, to disregard the analysed aspects of security culture, especially during the early stages of development. Awareness of a child’s varying needs that result from various developmental stages and adapting safety requirements to them are also valuable manifestations of a wise concern for a child and its future. The important parameter of such concern at every stage of life is security culture and the result of it – security.

Conclusions

In conclusion, security culture is a category that includes every security entity. Among the various definitions of security culture, its core is the approach to the issue of security, which is the basic human need. It can be perceived in numerous aspects and various elements can be taken into account to characterise it. Most of the studies indicate that security culture is based on certain foundations and has a certain structure. Its structure consists of both basic and detailed elements such as values, norms, attitudes, actions, cooperation, reasonable openness, wise trust and risk. The issue of security culture has become the object of various studies, which provide its models and indicate its importance in human life. The ideal model and the pyramid model presented in the study are the most comprehensive ones. Taking into account that the approach to security starts at the personal level and can be transferred to the level of groups, the idea of shaping such an approach seems to be particularly important. The research shows that the high level and appropriate nature of security culture can have a positive impact on the security of a subject and its environment, while the unfavourable form of security culture will have the opposite effect.

Based on the literature research, it can be stated that the basic outline of security culture is shaped during childhood and school years. It is shaped mainly in the family and in educational institutions. Educational institutions, however, have a limited impact in this area. They start the education of a child mostly at the age of 5 or 6. The first years are based solely on education in the family. These years have an enormous impact on a child’s approach to the issue of security. The foundations built then cannot be changed later. Moreover, the institutional education takes place for a limited time. Boarding schools are not common at the level of primary education, which means that many educational processes still take place at home. It is also worth mentioning that parents not teachers most often provide an example of certain behaviour. Such examples are provided on a daily basis so their influence on the values, norms, attitudes, actions and other elements of a child’s security culture is tremendous. Taking into account all these arguments, the role of family in shaping security culture among children is indisputable and it should not be overestimated.