Introduction

According to the latest report from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (hereafter: OCHA), nearly 168 million people were in need of some form of humanitarian assistance and protection at the global level in 2019, which is considered to be the highest number in the last few decades (OCHA, 2019, p. 4).

The nearly decade-long Syrian civil war and its humanitarian consequences have significantly increased the number of people that need external assistance and caused the largest displacement situation and refugee crisis since World War II. Since the outbreak of the civil war, almost 6.7 million people1 have fled their homes and sought refuge in safer countries near Syria, mainly in Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon. In these neighbouring states, the number of registered refugees is currently peaking around 5.6 million (UNHCR, 2020). As can be seen in Table 1, among the refugee-hosting countries in the region, Turkey has the largest Syrian refugee population, about 3.6 million people, followed by Lebanon and Jordan.

Table 1

Number of Syrian refugees in Syria’s bordering countries and Egypt as of October 2020 (UNHCR, 2020).

| Country of asylum | Number of registered Syrian refugees |

|---|---|

| Turkey | 3627 481 |

| Lebanon | 879 529 |

| Jordan | 659 673 |

| Iraq | 242 704 |

| Egypt | 130 085 |

As the decade-long conflict and humanitarian crisis in Syria remain unresolved, the circumstances continue to be unsuitable for larger scale repatriation of refugees. The protracted nature of the Syrian civil war has resulted in a chronic and persistent forced displacement situation in Turkey2 that cannot be considered as an acute and short-term emergency anymore.

With the presence of 3.6 million refugees, Turkey has not only become a country that is hosting the largest refugee community worldwide, but also the country most affected by the humanitarian consequences of the Syrian conflict (Erdoğan, 2020, p. 2). While Turkey regularly calls for more equal and effective burden-sharing within the international community (Erdoğan, 2016; Daily Shabah, 2019), the Syrian refugee situation in Turkey has not only caused socioeconomic, political and demographic upheaval but produced inevitable social and humanitarian challenges for both host and refugee communities. Besides the hardships of refugee camps, urban refugees also face severe humanitarian and social challenges such as food insecurity, exposure to poverty or extreme poverty, child labour or lack of proper education, and labour market access. Although the Turkish government is playing a remarkable role in addressing these challenges, international development and humanitarian initiatives should also be examined and discussed. This paper therefore attempts to investigate the international role and the central elements of its functioning. It focuses on the Emergency Social Safety Net Programme of the European Union, the World Food Programme and the Turkish Red Crescent and, furthermore, reviews the Turkish aspects of the Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan of the United Nations. The primary purpose of this study is to provide a comparative analysis of the two programmes alongside the main objectives, results and difficulties. Finally, the paper also investigates whether the development practices introduced are in line with the current trends of international humanitarian assistance. Beyond reviewing the essential international literature, the examination of this issue is principally based on the data analysis of relevant international organisations’ reports.

The Turkish refugee issue and the international response can be regarded as a mirror of a global paradigm shift. The protracted refugee and humanitarian situations questioned the traditional forms of assistance, challenged (and are still challenging) the capacities and resources of international and local aid organisations and host governments (WFP, 2015; Ferris and Kirişci, 2016). Moreover, the long-lasting humanitarian emergencies and the high proportion of refugees living in urban areas has led to a rethinking of international relief activities and modalities (Betts and Collier, 2017). In light of the above, it is important to analyse the crisis response potentials of UN agencies and try to understand how they may assist those countries that possess a stable economic performance and social welfare system but face constant refugee pressure. The examination of the UN’s involvement is particularly interesting in light of Turkey’s presence in the international development aid system as a donor state and not as a recipient (TIKA, 2018).

Hereby, it is important to highlight that (as we will see below) the Syrian refugee population in Turkey has not obtained official international refugee status, although we use the term “refugee” to address them in this paper.

Refugees in Turkey: legal-institutional framework and demographic characteristics Legal and institutional framework

Before discussing the social and humanitarian challenges of Syrian refugees in Turkey, the legal status of Syrian refugees and their demographic characteristics will be briefly reviewed.

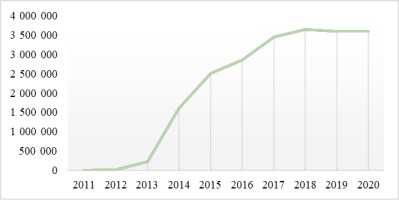

Turkey’s response to the arrival of Syrian refugees can be mostly described as centralised, and the legal-institutional framework has been specifically designed to manage the massive flow of Syrian refugees. The ad-hoc policies that initially promoted an “open-door policy” and referred to Syrian refugees as “guests” were replaced by the comprehensive nature of a legal-institutional scheme (Memişoğlu, 2018a; Bélanger and Saracoglu, 2019). It was necessary to create an extensive legal-institutional framework, as the continuing escalation of the civil war and the constant increasing of the refugee population (see Figure 1) made it clear that the refugee situation in Turkey had become more permanent and a long-term issue (Kirişci, 2014).

Giving official refugee status for the Syrian refugees in Turkey was hindered by the fact that Ankara did not lift the geographical restrictions in the Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees of 1951 and its Protocol of 1967 (Kirişci, 2012). Under this clause, only citizens of the Council of Europe member states are eligible for official refugee status in Turkey (Paçaçı Elitok, 2018). This geographical restriction, by definition, precludes the granting of official refugee status to refugees or stateless persons from Syria – and other countries in the Middle East or Africa. It is important to highlight that previous legal documents3 aimed at addressing the shortcomings of the Geneva Convention have not proved to be sufficient to deal with the intensifying influx of refugees from Syria (İçduygu, 2015; Memişoğlu, 2018b).

The legal bases for temporary protection status are laid down in Law No. 2013/6458. According to this regulation, “temporary protection status may be granted to all foreign nationals who have been forced to leave their countries of origin and who have crossed or intend to cross the borders of Turkey en masse in order to claim immediate international protection” (Law No. 2013/6458). This article of the law was thus the first to settle the legal status of Syrians in Turkey. However, given that it is temporary protection, a substantive clarification of the timeframe was not specified in the text of the law (İçduygu, 2015, p. 6). While the law and its relevant articles adopted in 2013 only sought to settle the temporary protection status and its conditions, the regulation on temporary protection adopted in 2014 set out the rights and obligations of persons with temporary protection status. According to this, the Syrian refugee population is entitled to enter the labour market; to access education, health and other social care, and to request a native interpreter (Ineli-Ciger, 2017, p. 559).

As the number of refugees increased, the Turkish government also adapted a relevant institutional framework for the changing circumstances. One of the most critical changes in the institutional system was the establishment of the Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM) under the Ministry of Interior in 2013. The Directorate is responsible for implementing all government policies related to migration, including policies with temporary protection status for stateless persons and victims of human trafficking (Law No. 2013/6458). The Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency (Turkish short version and hereafter the AFAD), has been also given an important role in refugee supply, coordinating the humanitarian aspects of the refugee crisis as a designated lead organisation. Until 2018, one of its most important tasks was to maintain and operate refugee camps, later, however, this task was transferred to the DGMM by the Turkish government (Memişoğlu, 2018b).

Geographical distribution and demographic characteristics of Syrian refugees

The Turkish authorities initially sheltered refugees in refugee camps4 along the southeastern border of the country5. However, the capacity of the camps could not keep pace with the steady increase in the number of refugees (Erdoğan, 2020, p. 21). As a result, the proportion of in-camp refugees has declined significantly over the years: while the proportion of people living in camps was 12% in 2015 (World Bank, 2015), according to DGMM, the same proportion did not reach 3% in 2020 (DGMM, 2020). So, more than 97% of the Syrian refugees live in urban areas of Turkey, mostly in southeastern provinces (Gaziantep, Hatay or Şanlıurfa) and the metropolitan area of Istanbul (see Map 1).

It is essential to add, however, that the proportions and data just described are slightly overshadowed by the fact that some refugees registered in the border provinces have left the province in which they were registered and settled in the western metropolitan areas of Turkey (Erdoğan and Çorabatır, 2019).

According to Turkish authorities, 45% of Syrian refugees are under the age of eighteen, while 38% are under the age of fourteen. Furthermore, approximately 80% are younger than 45 (DGMM, 2020). The 15-18 age group is roughly 250,000 people. Although we cannot consider the members of this age group as adults, mentioning them separately is justified by the fact that the upper age limit for obligatory schooling in Turkey is fourteen years. So, the participation of this age group in education provided by the Turkish government cannot be regarded as compulsory (Hürriyet Daily News, 2019b). The proportion of children aged four or younger is also significant: more than 490,000, so around 13% of the Syrian refugee population has not yet reached the age of five (DGMM, 2020).

Looking at the numbers above, it is clear that we can talk about an extremely young population of Syrian refugees, which, as we will discuss below, poses a significant challenge both for education and other social benefits, as well as in the labour market.

Social and humanitarian challenges

Social challenges have emerged among the Syrian refugee population living outside the camps, mainly due to the rising burden on the Turkish housing and labour market and education system; while it also stems from cultural and linguistic differences and tensions between the Turkish and Syrian populations (Kirişci, 2014; The Economist, 2017; Danış and Nazlı, 2018). The challenge comes obviously from the fact that off-camp refugees do not benefit from the conditions and equipment of camps.

Despite the relevant regulations, access to the labour market is far from straightforward: work permits can only be issued in the province in which the person is enjoying temporary protection and where she/he was registered on arrival to Turkey. Furthermore, in workplaces, Syrians should not exceed 10% of employees (Stock et al., 2016, p. 14; Ineli-Ciger, 2017, p. 561). According to last year’s WFP and Turkish Red Crescent report on the situation of Syrian refugees, by the end of February 2019, a total of 38,289 work permits had been issued to Syrian citizens with temporary protection status and a further 30,000 to Syrians with a permanent residence permit (Turkish Red Crescent and WFP, 2019, p. 6). This data shows that many Syrian refugees work in informal sectors without a contract of employment. In addition to the quota mentioned above, language barriers also constrain the participation in the formal labour market. Moreover, the high unemployment rate of the Turkish population, differences in qualifications, and the tendency for tax evasion by employers further complicate the legal contribution of Syrian workers (Ibid.). Exclusion from the formal labour market and rising costs of living, despite the financial expenditures of international aid organisations and the Turkish government, carry the risk of deep poverty. According to a 3RP report of 2018, 64% of urban Syrian households live below the poverty line, and 18% are in deep poverty (Karlstrom et al., 2018, p. 4).

In addition to unemployment and labour market difficulties, education is a crucial pillar of social challenges. As discussed above, a significant proportion of refugees are minors and the off-camp Syrian refugee children are guaranteed participation in Turkish public education, as well as the children living in camps. In addition to participating in Turkish public education, the Turkish government maintains so-called Temporary Education Centres (TECs) where school-aged Syrian refugees can study in their mother tongue (Erdoğan, 2020, p. 35). However, TECs provide education to only approx. 13,000 Syrian schoolchildren (Karasapan and Shah, 2018). It is important to highlight that the Turkish government is phasing the TECs out with the aim of more adequate integration possibilities. While altogether, only 63% of school-age Syrians participate in public education outside of TECs, it is noteworthy that this ratio is, of course, unequally distributed among different age groups. While the enrolment rate in primary schools is close to 90%, only 70% of high school refugees participate in education. (Daily Shabah, 2020; Erdoğan, 2020). Language difficulties, child labour, hard-to-reach educational institutions5, and other burdensome costs of education for families living in deep poverty can be blamed for the school drop-out rate (Khawaja, 2016; Carlier, 2018, p. 7–8).

When looking at education and employment, it is useful to address the problem of child labour, which is a remarkable, common social problem for school-aged refugee children all over the world. Even though it was not the Syrian refugee crisis that brought about child labour in Turkey, young Syrian refugees often enter the labour market through informal work mainly due to deep poverty and dropping out of school (Orhan and Senyücel Gündoğar, 2015).

In addition to the challenges just outlined, we have to mention the issue of citizenship as well as statelessness. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan announced on January 7, 2017, that some Syrian (and Iraqi origin) refugees could be granted Turkish citizenship if they passed specific screening processes (Al Jazeera, 2017). The granting of citizenship was also subject to conditions by the Turkish government, such as higher education, adequate language skills and no criminal record (Köşer Akçapar and Şimşek, 2018). Based on these stipulations, the number of Syrian refugees who acquired Turkish citizenship in 2018 was estimated at around 52,000 (Dost, 2018, p. 113). Regarding citizenship, it is important to highlight that statelessness is a significant challenge as children of Syrian parents with temporary protection status born in Turkey are not entitled to either Turkish or Syrian citizenship (Köşer Akçapar and Şimşek, 2018). In terms of numbers, between 2011 and 2018, 311,000 stateless Syrian children were born in Turkey, and by June 2019, the number of stateless newborns had risen to a total of 415,000 since the outbreak of the civil war (Middle East Monitor, 2018; Hürriyet Daily News, 2019b).

As for the attitude of the Turkish population, the initial hospitality towards Syrian refugees seems to have waned: while 72% of the Turkish population surveyed did not have a particular problem with the presence of Syrian refugees in 2016, 80% of the respondents embraced the repatriation of refugees to Syria in 2018. This significant change in attitude is primarily caused by the Turkish economic downturn in 2018, while it can also be explained by the permanency of the Syrian refugee problem and its increasing burden on Turkish society (e.g. the transformation of the housing and labour markets) (Karasapan, 2019).

International response

At the time of the first major influx of refugees, Turkey began resettling the incoming Syrians in camps at the Turkish-Syrian border as well as started providing different forms of humanitarian assistance to them (Memişoğlu, 2018a; Senyücel Gündoğar, and Dark, 2019). When it comes to the role of international organisations (especially the UN), it is crucial to emphasise that at the beginning of the refugee crisis, the Turkish government did not request any form of international assistance including missions of UN humanitarian agencies6 (Kirişci and Ferris, 2015, p. 9; Bélanger and Saracoglu, 2019) and international NGOs (Yılmaz, 2018, p. 7). An exception to this was the UNHCR guidelines on refugee camps, which Turkey applied from the beginning to set up and operate Temporary Accommodation Centres (McClelland, 2014).

After the intensely growing flow of refugees from 2012, the Turkish government decided to alter its original policies and approved the operations of UN agencies, while it has also initiated tighter partnerships with international actors in humanitarian assistance (UNICEF, 2015). Nevertheless, these organisations faced a critically new and unfamiliar situation when they started to participate in the assistance to Syrian refugees in Turkey (UNHCR, 2016). Their aid activities were launched in a refugee-hosting country with strong national leadership and – despite the rapid shifts in the institutional framework on a national level – an indeed well-resourced government. In the context of Turkey and its refugee situation, most of the earlier implemented relief methods were not relevant and not applicable; therefore, the UN humanitarian agencies needed to reconsider their manner of assistance (Ibid).

Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan

As mentioned above, the widespread and protracted refugee crises and the specific situation of Turkey have prompted the UN and its humanitarian agencies to rethink their humanitarian aid policies and to set up context-specific programmes.

With the escalation of the Syrian civil war and the increasing burden on host governments, the UN has laid the groundwork for tackling the refugee crisis in the neighbouring, host countries of Syria, including Turkey. This aim is clearly reflected in the Syria Regional Response Plan (hereafter RRP), launched in 2012. This was the first comprehensive, country-specific aid programme that brought together not only the relevant UN bodies but also international and local NGOs and created a framework for cooperation between the UN and national government institutions (Kirişci, 2020, p. 16). In addition to in-camp refugees, the programme extended its focus to urban refugees as well as host communities. The motivation behind benefitting host communities in RRP is to moderate tensions between members of (urban) refugee and host communities and acknowledging the harsh effects of the protracted displacement situation on host community members and local economies. Although the programme includes long-term goals and solutions7, the RRP responded mostly to urgent humanitarian challenges of the refugee crisis and focused more on acute emergency management such as life-saving relief and basic social services (United Nations, 2013).

In 2015, the Regional Response Plan was replaced by the Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan (3RP), which, in terms of its name, content and objectives, is more prominent in applying durable development policies and facilitating long-term management of the refugee crisis. This includes promoting the self-reliance of refugees, creating and protecting livelihoods and job opportunities and supporting long-term education enrolment (3RP, 2015, pp. 32–40, Kirişci, 2020, p. 23).

The 3RP, together with introducing resilience-related policies, has maintained its country-specific nature and the emergency relief modalities, such as access to basic needs and essential services. Moreover, the programme preserved the innovative approaches of the RRP, such as integrating the relevant UN agencies, (I)NGOs and national institutions and considering the needs of host communities (3RP, 2015). Integrating the UN organs, (I)NGOs and domestic organisations means that every segment of 3RP lead by a UN agency in a partnership with the most relevant national ministries (see Table 2). As Table 2 shows, the 3RP Turkey programme contains an interdependent and interconnected, yet diverse and broad range of objectives, which shows the undeniable complexity of the refugee situation in Turkey. It is noteworthy that each sector has a refugee/humanitarian component and a resilience component as well. This means that although the 3RP displays the importance of long-term development policies, it is still taking the urgent humanitarian needs of refugee population into account while creating a platform for connecting the humanitarian assistance programmes with promoting self-reliance among refugees and strengthening national capacities.

Table 2

Segments of 3RP Turkey with their leading UN agency, national institution and responsibilities (3RP Turkey Country Chapter, 2020, pp. 17–79).

One of the most significant innovations of 3RP, in addition to taking long-term solutions and resilience into consideration, is the statement that the programme is a complement to and a supporter of national policies, government regulations, and does not operate independently of domestic refugee programmes (3RP, 2020, p. 9). Alongside this objective, one of the main tasks of 3RP Turkey is helping the national public institutions handle the increasing need for public services. This goal is perfectly displayed in the proportion of the financial support received by public institutions: while 76% in 2018, and 90% in 2019 of the overall funding was channelled through ministries of the Turkish government (UNDP Turkey, 2020, p. 6). As for the most supported ministries and institutions, the Ministry of National Education, the DGMM and the Ministry of Family, Labour, Family and Social Services have been given the most financial assistance since 2017 (UNDP Turkey, 2020, p. 6), which shows the remarkable and crucial role of these public institutions in dealing with the massive refugee influx.

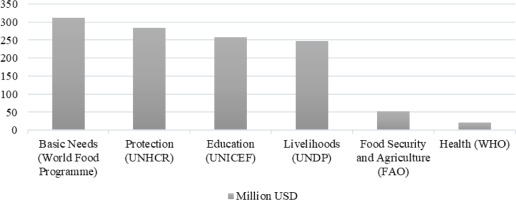

Regarding budget requirement, it can be seen in Figure 2 that funding needs are unequally distributed among the various segments. It is clear that the demand of basic needs8, protection and education are the highest, with around 300 million USD each, while the needs of the health sector do not reach 30 million USD. These differences in budget requirements undoubtedly reflect the main social challenges and gaps of Syrian refugees residing in Turkey, such as exposure to extreme poverty, negative coping strategies, struggling to have access to adequate legal protection, education and the labour market.

Because of it being such a large-scale aid programme and the protracted nature of this emergency, challenges and shortcomings proved to be inevitable. Since its launch, the 3RP in Turkey has been struggling with budget gaps. In previous years, the refugee/humanitarian component of the programme was almost entirely funded: 80% and 73% of the financial requirements were met in 2018 and 2019 respectively. On the other hand, in the case of the resilience component with long-term projects, this proportion was only 40% both in 2018 and 2019 (Karlstrom et al., 2018, p. 4; 3RP, 2020b, p. 9).

Emergency Social Safety Net Programme

Although the Emergency Social Safety Net Programme (ESSN) is included in the 3RP framework9, it is worth handling and discussing it separately as a main form of international assistance in Turkey. The ESSN Programme launched in November 2016 was funded by the European Commission10 and implemented by the World Food Programme and the Turkish Red Crescent to assist the most vulnerable refugees with high levels of food insecurity and extreme poverty (Turkish Red Crescent and WFP, 2018; ECHO, 2020). It is important to highlight that as the whole 3RP framework does, the programme operates through the Turkish government and the social welfare system with the help of important government stakeholders11 (WFP, 2016a, p. 8).

The ESSN aims to tackle the most urgent humanitarian challenges of Syrian refugees in Turkey with multi-purpose, unrestricted and unconditional cash assistance on a debit card by monthly donations (WFP, 2016b). This relief method is regarded as an innovative approach to dealing with the urgent humanitarian needs of Syrian refugees in Turkey, and is often cited as the largest humanitarian aid programme in the world assisting forcibly displaced people (Parker, 2019; Turkish Red Crescent, 2020). It is innovative in the sense that cash-based assistance is considered as a highly inventive form of humanitarian relief, as it encourages the people that are benefitting12 to choose and decide what goods they need the most (Tappis and Doocy, 2017; Heaslip et al., 2018).

It is clear that the main objective of the programme is to provide emergency relief for refugees to meet their basic needs. On the other hand, ESSN set the goal to reduce the chance of extreme poverty in the long run with promoting self-reliance and negative coping strategies, such as child labour, limited food consumption or selling assets. Moreover, promoting social cohesion and boosting the performance of the local economy is also among the priorities, since the refugees spend their received cash assistance in local shops (WFP, 2016b).

Regarding the target population of ESSN, it is important to highlight that the programme applies eligibility based on demographic targeting criteria. These criteria include ‘(1) households with four or more children; (2) households with more than a 1.5 dependency ratio; (3) a single parent with no other adults in the family and at least one child; (4) household consisting of one female; (5) elderly people with no other adults in their family; (6) households with disabled persons’ (WFP, 2018, p. 9). According to the European Commission, around 1.7 million people were (and still are) being assisted through ESSN in 2020, where each member of the eligible families is entitled to receive 120 Turkish Lira per month (European Commission, 2020). According to the reports from the implementing organisations, the living conditions of assisted families have improved as a result of the monthly cash support through ESSN (WFP, 2018; WFP, 2019). However, a World Bank report draws attention to the fact that the ESSN should reconsider its eligibility criteria, as more than 30% of refugee households in need do not fit the demographic targeting criteria (Cuevas et al., 2019, p. 41).

With regard to the relationship between the Turkish government and the ESSN, it is noteworthy that in 2018, Ankara expressed its intention to leave the cash assistance programme. In the same year, the Turkish government prepared an ESSN Exit Strategy report aiming to promote even stronger self-reliance and more decent job opportunities among the refugees (Government of Turkey, 2018). On the other hand, no significant progress has been made on this issue yet (Parker, 2019).

Conclusion

The study attempted to outline the most important characteristics of the Syrian refugee situation in Turkey, while it presented the primary forms of international aid activities and domestic policies. The widespread and protracted refugee crisis and the specific situation of Turkey have prompted the international community to rethink their humanitarian aid policies and to set up context-specific methods.

It can be seen that the Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan focuses on a wide range of objectives and challenges, such as reduction of extreme poverty, long-term education enrollment and livelihood opportunities. The framework brings together several UN agencies, (I)NGOs and national stakeholders and tries to find the balance between urgent humanitarian needs and durable solutions. Although the responsibility of the EU-funded ESSN is to respond to basic needs of refugees, both initiatives put a considerable emphasis on host communities, social cohesion and the local economy. It is clear that the Turkish government and its institutions play a crucial role in handling the massive refugee influx on its territory, and it is clear that international policies operate as a completion of domestic policies.

Finally, the study highlighted the social and humanitarian challenges of refugees in Turkey, which have come about because of the permanent nature of the Syrian refugee issue. Despite integration measures, the reception of nearly four million refugees has social consequences for the refugees. These challenges include the risk of deep poverty; difficulties of legal employment and integration; tensions between the local Turkish population and the refugee population; participation in education and the issue of child labour and, in the case of newborns, statelessness.

Beyond the remaining obstacles, gaps and the undoubted complexity of the Turkish refugee situation, it can be concluded that the aid initiatives discussed above have developed innovative solutions to address this protracted crisis. On the other hand, numerous factors (e.g. Turkish domestic policies and the situation inside Syria) will influence the outcomes of these policies, while the recently escalating tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean may also generate new and seemingly unseen challenges.