Introduction

Compulsory military service is a model that has been disappearing in the Western world since the 1980s due to changes in social values, in the nature of military confrontations and technological advances on the battle field (Krebs, 2009). Today, the leading concept in the western world is ‘professional army’, recruiting only those who are interested. The service therefore became limited to restricted minorities (Hajjar, 2014). Furthermore, in some countries, including Israel, the army is still based on the concept of ‘Army of the People’, involving compulsory and reserve duties. This is for several reasons: the nature of security threats, the size of the population when compared to geographical dimensions, and social motivation (Tamari, 2012). These countries view the army as a socialisation mechanism, instilling cultural values, and formulating the nature of society and its solidarity.

In the past decade, there has been growing discussion in Israel as to the social needs of a ‚citizen-soldier’ military: supporters of the model claim that military duty is still an effective socializsation mechanism as an integrator (Stern, 2009). Opponents of the model claim that military service enhances social tensions, creating a gap between the religious and secular population (Levy, 2014), and reinforces Islamophobia, leading to demonisation of Arab national minorities (Gabizon and Abu-Riya, 1999). In addition to that, most studies on the Israeli army (IDF) in the last decade focused on the motivation to enlist, hence a knowledge gap regarding the social effect had been created, mainly on the potential of the service as a social integrator.

The current study tries to give answers to this challenge, focusing on the contribution of military service to social and national aspects. This study sets out to answer the research question whether compulsory military service in Israel is still functional as a social integration platform. This has to be followed by three secondary questions that can explain the social and the national effectiveness of the service:

Defence belief

Since Israel’s independence year (1948), the Israeli army (IDF) has been a mechanism of solidarity that has led to a ‘siege mentality’ as an evolving defence belief of a Jewish ethos. This phenomenon was an outcome of the brutal history of deportation, the Holocaust and wars of survival (Lewin, 2013). According to Lewin, the characteristics of a ‘defence belief’ is based on four main ideas: the state is a vital condition for the survival of Jews; there will always be a war for survival; the only way to survive here is to win wars, hence “only a great army will give us salvation”. According to Lewin, a strong ‘siege mentality’ constructs a defence belief that is based mainly on fear of war and terror.

Ruth Gabizon, a former Israeli judge and a law expert claimed that security threats around Israel can enhance fear, which might lead to hatred towards minorities, especially Arabs and Palestinians (Gabizon, 2003). This aspect also affects citizen’s attitudes towards security, and Israel’s defence budget, which historically has been high over the years (Shelah, 2015). Hence, welfare and other life quality issues, such as medicine and education, were rated low in the priority order. It is well known that Israelis support a high defence budget, but nowadays this is an issue that is much disputed (Shelah, 2015).

In the past decade, service in the IDF is considered as a potential “turning point” as to exsoldier’s attitudes towards security threats and towards Arabs, especially Palestinians and there are researchers who claim that military service in the IDF could be a moratorium that changes even the soldier’s prejudices and beliefs (Colonimus and Bar-Tal, 2011).

Therefore, the question that has to be examined is about soldiers real understanding of security threats, especially after experiences and information to which they are exposed to during military service, and the way that it affects national and social attitudes.

Sense of security threat

The sense of the security threat ‘resides’ permanently among Israelis (Itsik, 2013). However, a longitudinal study that has been conducted among citizens about Israel’s resilience since the year 2000 found that the threat level measured has decreased since 2009 (Ben-Dor and Lewin, 2017). Furthermore, it is claimed that four generations after the establishment of the state of Israel, society has adjusted to terror threats as the only non-Arab state in the Middle East (Shiftan, 2007).

In addition to that the above, Shor and Nevo, who interviewed IDF soldiers and commanders, claim that the Israeli soldier has become more tolerant towards Palestinians over the years (Nevo and Shor, 2002). According to their findings, the reason for that change of attitude is the general orders about the need to “beat terror and remain human-beings”. These orders were followed by an ethical moral code and strict supervision which changed the point of view about Arabs in general, and particularly Palestinians as human beings.

The question that has to be asked is about the value effect during military service – has there really been a significant change? Are ex-soldiers really more tolerant towards Arabs, and what are the values that have been enhanced during military service?

Value effects of military service

There are opposing claims relating to the effect of the nature of army duty on individual moral values: on the one hand, it is claimed that emotional experience during war may evolve into extreme nationalism (Hacohen, 2014). On the other hand, it is claimed that the service has a moderating effect on attitudes towards minorities (Rennick, 2013). Bar-Tal and Staub who studied aspects of patriotism found that army duty might affect patriotism in two ways: blind patriotism, based on nationalism and hatred towards minorities, and constructive patriotism based on inter-cultural balances and mutual respect (Bar-Tal and Staub, 1997).

Research that was conducted recently in Poland’s military academy found that students of military classes indicated the following to be conducive to strengthening during military service: respect for national security, tradition, and national symbols, patriotism, national awareness, social activity, belonging, community, and the building of a civil society (Urych, 2017) – this could be an indication of constructive patriotism.

Yael Tamir, a sociologist and a former Israeli minister of education, claimed that in multi-cultural societies, there can be mutual respect and tolerance, which depends on normative socialisation platforms (Tamir, 1998). Samia, a researcher and a former General in the IDF, found that cohesion in military platoons forms tolerance towards other cultures (Samia, 2008). Another study found that the IDF applies a multifarious concept of religion with significant impact on the ability to foster a sense of ‘‘us’’ (Røislien, 2013). This phenomenon was also described by Elazar Stern, a former general in the IDF, who was the head of human resources (Stern, 2009). Stern claims that during military service, mutual honour between cultures is intensified and also between Jews, Druze, and Bedouins, who are actually Muslim Arabs.

If service in the IDF causes actual pluralism, it is genuine proof that it is a functional integration platform, which also bridges tensions between Jews and Arabs, a major conflict area in Israeli society. The IDF can therefore perform constructive patriotism.

Most Israeli studies on army and society issues in the past decade have focused mainly on motivation for army service. Few have examined value aspects, and even those that did used traditional data collection platforms, creating a reduced perspective for examining this phenomenon. The current study will extensively examine the effects of service in the context of threat concepts and social values, based on an innovative wide platform that can better portray reality.

Methodology

In the past decade, most studies dealing with the social and cultural implications of serving in the ‘citizen-solider military’ have used the qualitative method. Even studies relating to the effect of serving in the IDF have used similar tools except for a few cases that used the quantitative method to identify value and identity effects of military service on the mass population (Barkai, 2007).

This comparative study is based on wide sampling: 3200 individuals similar to the population serving in the IDF answered internet questionnaires. The participants in the survey reside in all parts of the country, half of them are women and the other half men, and their distribution in terms of type of service, level of religiousness and socio-economic level are similar to those serving in the IDF.

The study tool used was an anonymous internet survey based on a structured questionnaire distributed via social networks in the years 2015-2018. This method allows access without geographical difficulties and also targets unique groups in the population from whom it is difficult to collect data using traditional methods.

The participants had to rank their opinions on different statements relating to defence belief, the concept of security threat, and social challenges, by means of a 1-6 Likert scale. The statements to which the participants had to refer in the questionnaire were based on surveys that were conducted before, and in 3 main sections:

Categories of “siege mentality” were used in the section that examined the concept of defence belief (Lewin, 2013).

In the section that examined the concept of existential threat, the questions were taken from Israel’s resilience study (Ben-Dor and Lewin, 2017).

The section of social values combined statements that were used in the Israeli annual report of the Israeli Democracy Institute (Harman et al., 2013), and the “Israeli Jew” survey (Arian, 2009).

The findings are based on comparing the attitudes of two groups, ex-soldiers who were released after compulsory service in the IDF, up to the age of 24, and high-school students from 16-18, followed by U-test analysis.

Analysis

Table 1 gives an overview of the results according to 11 statements that participants had to rank on the Likert scale. In almost all of the statements, the percentage of ex-soldiers is low compared to high school students in the upper ranks (5–6), when it concerns fear, and high in the categories of social values.

Table 1

Statement rankings: ex-soldiers after service (a.s.) / high-school students before service (b.s.) %, n=3200

In Table 2, where descriptive statistics are shown, it can be seen that most of the participants inside the groups are consensual about most of the topics that were studied.

Table 2

Descriptive statistics of answers to statements (n=3200, range 1-6)

In Table 3, which provides U-test results of the comparison between the groups, it can be seen that most of the results provide a significant answer to the differences between the two groups.

Table 3

The Mann-Whitney U-test, student / ex-soldier (n=3200)

The concept of defence belief

In the internet questionnaire, participants were asked about their opinions regarding the four characteristics of Lewin’s model for ‘siege mentality’. The summary of responses points to the differences in defence belief between high-school students and the ‘fresh’ ex-soldiers released from compulsory duty.

In comparing answers relating to the State of Israel as an existential precondition for the Jewish people, 60% of the ex-soldiers tend to identify or fully identify with the statement, as compared to 63% of the high-school students (Table 1). The U-test (Table 3) between the two groups gives an insignificant result. The average answer scale of the two groups ranges between 3.9 and 4 (Table 2).

In conclusion, in relation to statement no.1, there is no significant difference between high school students and ex-soldiers. However, both groups average ranking shows that the idea of Israel as a precondition for Jewish survival tended to be accepted. This finding can signal for a “defence belief” in the two groups; however, the deviation in both groups is high, so we can understand that this issue is under debate.

In comparing the results for the statement “Forever live by the sword”, 53% of the ex-servicemen tend to or fully identify with the statement, compared to 59% of the high-school students. The largest difference is in the category “totally disagree” where the rate of respondents among the ex-servicemen is higher by 5.2%.

The U-test gives a significant result for this issue (Table 3), while both groups rank the idea between 3.5 and 3.8 on average (Table 2). It can be said that in relation to the thought of eternal wars, ex-soldiers are more optimistic than high-school students.

In relation to the statement “Cut security budget for other plans”, 68% of the ex-soldiers do not view the security defence budget as the highest priority, while 53% of high-school students think it is. In both the higher categories, the differences are clear: 43% of the ex-servicemen believe that budget should be moved from defence to other areas, while 29% of the high-school students believe this.

According to the U-test (Table 3), there is a significant difference between the two groups and, furthermore, the average ranking for this statement is 4.1 among ex-soldiers compared to 3.7 among students (Table 2). This finding can prove that ex-soldiers are more socially oriented when it concerns the implications of a high security budget.

Comparing responses in relation to the concept of danger in establishing a Palestinian state, there are clear differences between ex-soldiers and high-school students. While 47% of the ex-soldiers view the establishment of a Palestinian state as an existential danger, 60% of the students believe it is.

According to the U-test (Table 3), the differences between the two groups are significant, where ex-soldiers rank the statement 3.5 compared with 4 among students. Nevertheless, both groups rank the threat of a potential Palestinian state above 3 with a high level of deviation (Table 2) – this could be a sign that this issue is a topic of debate among these groups.

To sum up defence belief measures, most of the findings point to significant difference between ex-soldiers and high-school students. While high school students tend to adopt a strong defence belief, shown as a constant defensive approach, identifying Israel as an existential condition for the Jewish people, determining defence as the highest priority in allocating national resources, and viewing a Palestinian state as an existential threat, ex-soldiers view things differently and their concept regarding these issues is significantly more moderate. However, the findings show that some of the ideas are a topic of debate in both groups.

The concept of existential threat

In a longitudinal study conducted annually since the year 2000 regarding the national resilience of Israeli society, the researchers Gabriel Ben-Dor and Eyal Lewin (2017) examine the index of security threats such as war, terror and anti-Semitism among Israeli citizens.

Ben-Dor and Lewin identify that since the year 2000, there has been a slight yet fluctuating decrease in the level of fear from security threats among Israeli citizens. The current study measured levels of fear in relation to security threats among high-school students and ex-servicemen.

From the ranking for the statement “Chance of war in the next 2 years”, it can be seen that in categories 4 and 5 (tend to agree and agree) there are almost no differences in relation to fear of war. Nevertheless, in 6 there is a significant difference – 43% of the high-school students fear a war soon against 37.6% of the ex-servicemen. It may be said that both populations fear war in general, 87% of the ex-servicemen and more than 90% of the high-school students. According to U-test results (Table 3), there is a significant difference between the two groups concerning an incoming war. However, the average ranking for both groups is very similar (5 out of 6), with low-level deviation and this could also be a sign of a “defence belief”.

When the analysis deals with fear of being hurt by terrorism, there are clear differences between the two groups – 78% of the high-school students fear obeing hurt in a terrorist attacks, in comparison with 61% of the ex-soldiers (Table 1). The differences are even clearer in the higher categories: 36% among ex-soldiers compared to more than 52% of the high-school students. U-test results show this parameter as significant, with an average scale of 4.5 among students compared with 3.9 among ex-soldiers. In this parameter too, it can be seen that both tend to agree with the threat of being hurt in a terrorist incident in Israel.

With regard to fear of antisemitism, there are clear differences between the two groups: 60% of the ex-soldiers describe such fear compared to over 71% of the high-school students expressing fear of antisemitism. The U-test result shows a significant difference between the two groups (Table 3).

In summary, the fear index points to a significant difference between ex-soldiers and high-school students. It may be said that ex-soldiers fear security threats less than high-school students. However, both groups rank security threats above level 3 and this is a sign that external threat still exists among these groups, although at a moderate level.

Social concepts

The discussion on the social effects of military service will relate to measures taken from several sources: a study relating to Arab society in Israel, dealing with agreeing to have Arab neighbours (Smooha, 1992), and a study relating to the democracy index in Israel (Harman et al., 2013). An additional measure relates to the issue of the ability of the Knesset (Israel’s parliament) members to dismiss another member, an authentic issue, which clearly conflicts with the democratic principle: ‘rule of the people’.

Analysis of the findings relating to agreeing to have an Arab neighbour show that there is almost equality between the sampled groups (Table 1). The U-test result (Table 3) shows no significant difference between the two groups on that issue. Nevertheless, both groups average ranking is 3.6 out of 6 with a low-level of deviation (Table 2). It is therefore impossible to claim that military service positively affects openness towards Arabs, but it can be said that it has no negative effects. It seems that both groups have a moderate opinion regarding having Arab neighbours.

To sum up, more than 75% of the respondents replied positively to this question, almost 65% of them in the higher categories. This shows that both ex-soldiers and those facing enlistment in the army do not see a problem living next to Arabs.

The issue examined in the statement “Terrorists should have access to lawyers” relates to equal rights in society, emphasising the right to legal representation. The findings show that 59% of the ex-soldiers believe that even criminals of a nationalist nature should be allowed legal representation, as opposed to 49% of the high-school students. The U-test results show significant differences between the two groups (Table 3), while ex-soldiers average ranking is 3.8 compared with 3.4 among students (Table 2). Furthermore, the deviation level is high and similar in these groups, so it can’t be said that ex-soldiers are more moderate, but this issue is a topic of debate for all.

The freedom of speech is an elementary right in a democratic regime. This statement relates to the issue during war. 75% of the ex-soldiers believe that even rivals are to be allowed freedom of speech during war, while about 71% of the high-school students believe so. In ranking 6, the results are significant with a 6% change of attitude. The U-test results show significant differences, while ex-soldiers average ranking is 4.5 compared with 4.4 among students. It may thus be stated that military service does not hinder expressing this democratic value in extreme times.

The issue “Members of Parliament can impeach others” relates to the understanding of the right to choose or to be chosen, a benchmark in parliamentary democracy. This issue was discussed several times in Israel in the past few years, in view of the support of certain Arab Knesset members of terrorist organisations.

The findings show that 53% of the ex-soldiers believe that Knesset members should not be allowed to dismiss other members, while 49% of the high-school students believe so. In the “totally disagree” index, there is a major significant change of 7% between the groups (Table 1). The U-test in this parameter results in an insignificant difference between the two gropes, but close to being significant (Table 3). Ex-soldiers’ average ranking for this issue is 3.8 compared with 3.4 among students, with a high level of deviation (Table 2).

According to these findings, it cannot be claimed that military service prevents agreement with the above democratic right. Nevertheless, the findings show that 50% of the young people in Israel believe that Knesset members should have the right to dismiss others.

To sum up, these findings show that in almost all aspects studied, the ex-soldiers are more moderate in their views than high-school students. We may deduce that military service does not lead to extremism and it can be said that ex-soldiers are more tolerant of social and national conflicts, although both groups show a medium level of “defence belief ”.

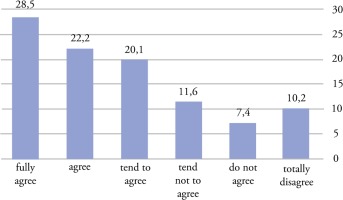

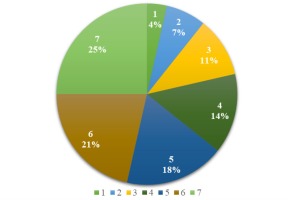

Furthermore, when ex-soldiers were asked about the effect of military service on their tolerance towards other cultures, a more than 60% agreed that during service they became more tolerant (Figure 1). When the characteristics of these soldier’s service were examined, it was remarkable to see that most of them had actually been together for more than 5 days a week (including nights) during 3 years of military service (Figure 2).

Figure 1

Ex-soldiers answers to the statement “Soldiers become more tolerant towards other cultures during military service” (%), n=1400

Figure 2

Military service characteristics of ex-soldiers who participated in the questionnaire analysed by days and nights spent together in a week, n=1400

This could be important evidence for an effective socialisation process.

Discussion

The findings above show significant differences in the concept of security fears, the perceived defence belief and social attitudes between those who finished their compulsory service in the IDF and those before enlisting. Discussion will hopefully provide reasons for these differences.

The erosion of the defence ethos during military service in the IDF seems opposed to logic, since the IDF is constantly in contact with close and distant enemies. The rhetoric of political leaders in Israel, mainly in relation to the Iranian threat, loudly expressed during the past decade can be added to this.

Moreover, the change in soldiers’ attitudes could be for several reasons and their common denominator is the change in the nature of the confrontations. This is an era of ‚hybrid’ confrontations against subversive and terrorist actions. The fighting is less combative and more narrative-communicative (Elran, 2006). This is an era of wars without winners (Ben-Eliezer and Al-Haj, 2006), which can also be characterised by the penetration of civil practices (Levy, 2009).

As it well known, there has been a significant transformation in the nature of the battlefield in the last decade, which is currently saturated with technological abilities (Kopka, 2019) and fighting concepts that strive for a dramatic reduction in the danger to human lives (Lutwak, 2002, pp.73–102). Coping with these threats is usually achieved by means of media and technology. This process is turning the IDF into a ‘neo-professional’ army (Ben-Eliezer, 2012). Moskos claimed that in the western world, this process is defined as the ‘post-modern’ stage of an army, coping with low-grade threats, defending borders of peace, and coping mainly with challenges of nature (Moskos, 2000). In addition, there is a change in the mix of servers, including extensive investment in the army as a social mechanism leading the socialisation process.

The former Israeli Commander in Chief, Lt. General Gadi Eisenkott, recently expressed a view on the concept of security threats, emphasising two aspects: the danger of damaging the dignity of the IDF, involving it in social struggles over the image of Israeli society, taking place at the army’s expense; and that the IDF is invincible now and in the near future. These two contexts show that the commander of the IDF does not perceive any security threat that is an existential one. In his opinion, the struggle in society is in jeopardy.

In addition to Eisenkott’s ideas, his deputy, MG Yair Golan, has often reduced the strength of security threats, emphasising social threats resulting, according to him, from radicalisation processes in Israeli society. The opinions of the two most senior officers in the IDF show that Israel’s main challenge is not defence related, but social and internal. The narrative described by the IDF commanders is considered extremely reliable (Harel, 2013, pp. 107–125), and soldiers get the message loudly and clearly.

There has also been a reduction in fighting setups, the establishment of instrumental units, and a sharp reduction in calling up reserve personnel and coping with many non-combative missions. Therefore, it is not surprising that these phenomena ‘mask’ the nature of the threats (Itsik, 2019). The social preoccupation in the army has become more significant over recent years. This is seen in the quotations above from the speeches of Lt. General Eisenkott and his deputy.

At the beginning of the last decade, the Behavioural Science Division of the IDF presented the view that its main activity was the effort to conserve the ‘citizen-soldier military’, especially the values of uniformity, equality, and integration, in addition to dealing with absorbing new immigration and ultra-religious youths (Tishler and Hadad, 2011). As this study has found, these perceptions have been fulfilled.

The IDF’s attempt to connect basic republican and liberal values do not operate in a vacuum, but relates to a commanding staff that has varied views (Popper, 2009), leading to soft social multi-culturalism (Nevo and Shor, 2002). This concept has dictated the ‘spirit of the IDF’ as a normative frame work that puts human dignity at its centre, assimilating such values as civic duty and tolerance towards others (Nevo and Shor, 2001). This liberal concept, where commanders lead soldiers as equals, in a service where everything is negotiable, gives legitimacy to even refusing an order that a soldier regards as immoral (Yair, 2011, pp. 62–85).

Conclusion

The findings of the current study show that ex-soldiers for whom the defence belief has weakened, with a reduced threat picture, are more sensitive to social aspects, and tolerant towards Arabs. This means that the intention of the IDF high command to create an ideological-social balance during military service is effectively implemented.

These findings, as well as the dramatic absorption of technological abilities and strengthened measures against cyber threats raise the question of whether the IDF is a ‚post-modern’ army, and whether an army can be post-modern and, simultaneously, be a ‚citizen-soldier’ army.

These findings show a significant attitude shift in ages 16 to 24 – this echelon in society is the future of the state of Israel. The fact that military service in the IDF has seen moderate social attitudes evolve is essential for a democratic and pluralistic society.

Given the fact that Israeli society is in a continuous conflict with itself, this is an astonishing finding, and it can be said that at least Islamophobia isn’t derived from military service in Israel, or demonisation of the other side. It seems that the outcome is the opposite – serving in a citizen-soldier army in a democratic state could build bridges for major social and national conflicts and be an integration accelerator.