Introduction

Armed conflicts are generated by roots, often referred to in literature as causes (Cash-man, 2014). They are factors that constitute the grounds for the conflict and result in challenges to the existing relationships, norms and rules, as well as decisions in the process of policy making of parties to the conflict. The roots lead to the rise of differences in the mutual perception of the parties and also change their recognition and judgment of events, assets, security or equality. They create a foundation on which the divisions of society (‘us’ and ‘them’) and measures to define the object of disputes (i.e. the problem of the incompatibility of aims and interests) are built.

The aim of this study is to show the roots of armed conflicts based on an analysis of a variety of theoretical approaches. There are different theoretical approaches regarding the identification of the roots of armed conflicts. According to Carl von Clausewitz who represents a state-centric approach to war which relates to the traditional understanding of a conflict as an inter-state war, the roots of conflicts are to be found in human activity, in human factors such as rational political calculations, insufficient or inaccurate intelligence, the aversion to take risks and the inability to use all one’s forces at once. Clausewitz argues that war is a natural occurrence of man’s social existence, being a social activity between actors with a will of their own and with hostile feelings and intentions and emotions. The aim of war is to impose one’s will on one’s opponent through the use of force. The nature of war is adaptable, depending on actors, purpose, and even the means available at the time. War might therefore be compared to a chameleon and each era has had its own wars (Clausewitz, 2008; Landmeter, no date).

Quincy Wright (1983, pp.108–114) noted that an examination of the causes of war requires not only understanding the meaning of the term “causes” but also the meaning of the term “war”. When defining “war”, one has to take into account the technological, legal, sociological and psychological aspects because each and every one of them, in an individual, characteristic way, influences the view of this phenomenon, its nature and environment. In the technological aspect, the cause of war is “the need of political power confronted by rivals continually to increase itself in order to survive”. As far as the legal aspect is concerned, war is started due to “the tendency of a system of law to assume that the state is completely sovereign”. In the sociological area, it ought to emphasized that it is the “the utility of external war as a means of integrating societies in time of emergency” which causes war. At the psychological level it may be observed that “persons cannot satisfy the human disproportion to dominate except through identification with a sovereign group”.

Kenneth Waltz’s concept of analytical levels’ causes of armed conflicts has been chosen as the methodological framework for the purpose of this research. He suggests analysing the causes of conflict on three levels: (1) the level of the individual; (2) the level of the state; and (3) the level of the international system (Waltz, 2001). The choice of this approach is determined by the fact that it offers a multi-level framework. Moreover, the analytical categories identified by Waltz are in line with the understanding of the actors in security studies, the individuals, states and the international system of which consistently remain.

The monographic method, case studies and diagnostic survey with the technique of content analysis were chosen to conduct the research. The results of the research will answer the following question: What factors are the roots of armed conflicts? What is more, these will also allow a proposal to be put forward for the systematisation of the roots of armed conflicts.

The level of the individual

Waltz (2001, pp. 16–79) argues that wars are often caused by human nature and the nature of particular political leaders, such as the leaders of states. The causes of conflict are seen in biological factors including innate instincts, imperfections of human nature and psychological factors–such as aggression and frustration.

Cicero was one of the first scholars to point to insatiable human desires as the roots of a conflict, namely the desire to accumulate wealth and the pursuit of fame, which are satisfied by war (Zwoliński, 2003, p. 18). A similar stance was taken by Plautus, who believed that one should seek the roots of war in human nature, in innate biological qualities. As part of the human nature is hostile to other parts, since ‘man is wolf to man’(homo homini lupus), he stated that the intensification of this hostility as life runs its course can lead to the outbreak of a conflict (Zwoliński, 2003, pp. 18–19). This thought was further developed by Hobbes, one of the leading advocates of the biological theory of war. According to him, the origins of war lie in the traits of human nature, i.e. rivalry, distrust, and lust for fame, and these in turn inevitably lead to a war of all against all (bellum omniam contra omnes). The lust for fame is the cause of wars that aim to achieve or reinforce social status. As for rivalry, people start wars for profit and when the impulse to take action is distrust and the need to ensure their security (Hobbes, 1954, p. 109). In these circumstances, conflicts can be prevented by subjecting citizens to established rules for the functioning of the state and social life (referred to asthe social contract), i.e. accepting the authority of the state to regulate the principles of social and political coexistence.

By contrast, in Holbach’s view, the genesis of conflicts lies in the defects of character of outstanding individuals and leaders, which frequently result in fortuitous wars (Holbach, 1957, p. 147). People’s individual characteristics, especially negative ones, influence their perception of reality and thus influence their decision-making process. According to Garnett (2013, pp. 19–39), poor decisions made by politicians and mistaken judgements should be seen as the cause of armed conflicts. Conflicts occur as a result of mistakes, miscommunication, or a tragic consequence of an erroneous assessment of the state of affairs. Its cause is more human imperfection or fallibility than malice.

Another cause of conflicts is aggression, most commonly perceived as a result of frustration. Allen and Anderson (2017) indicted a wide range taxonomy of aggression e.g. verbal, physical, postural, relational, direct and indirect, action, physical, psychological, transient, and lasting. Dollard et al. (2017) noticed that individuals experience a sense of frustration when they realise that their aspirations, goals and desires are being suppressed. The growing frustration seeks an outlet, and thus the tension is released through aggressive behaviour, which provides relief to the frustrated person. Sometimes, individuals project their own suppressed desires and aspirations onto substitutes, e.g. a group, tribe or state. Appropriate organisation of society (i.e. social engineering) can minimise the level of frustration and transform aggression into harmless activity (e.g. participation in sports) by triggering the well-known psychological phenomenon of sublimation (Dougherty and Pfaltzgraff, 2001, pp. 269–270; Breuer and Elson, 2017).

Armed conflicts result from unmet needs at the individual level (including groups and society) necessary to live, function and feel satisfied. Maslow (1954; 1973) pointed out a broad spectrum of needs, e.g. basic needs – physiological, the needs of safety, social needs (belonging to a group), esteem, and the need for self-actualisation. The basic needs are dominant over all others, as the individual seeks to satisfy these first of all. Therefore, these determine the nature and character of human behaviour. The satisfaction of these is a prerequisite for the satisfaction of others. The outbreak of conflict occurs when people’s ability to satisfy the basic needs is widely limited.

Burton (1990; 1997) claims that the main cause of social conflict is ignoring the needs of the group, which leads it to turn to the use of force. The issue of the satisfaction of needs is used by groups as a manipulative tool to produce a dehumanised image of supposed ‘others’ through the incorporation of education and culture. On the other hand, it is the state’s duty to ensure that universal human needs are satisfied. Collapse of the state is one of the main reasons for contemporary conflicts.

Max-Neef and Rosenberg stress that meeting needs is an essential prerequisite for the prevention and resolution of armed conflicts. According to Max-Neef (1987), it is important to analyse the mechanisms of satisfying needs and the factors that affect this process, e.g. the development of technology, the impact of globalisation on the activity of local communities, the relationship of the individual with the group/society and of groups with the state. Rosenberg (2003, pp. 3–7) notes that by understanding needs, it is possible to prevent violence and destruction, which are a tragic expression of the failure to satisfy these. Education and culture can influence the way people take an objective view of actual needs, including both their own and those of others. That is why a number of activities in the field of upbringing and education, especially of young people, is so important. These include the transfer of knowledge, shaping attitudes and personality development in order for it to function efficiently in various aspects of life (Urych, 2019, p. 27).

The level of the state

At the level of the state, Waltz (2001, pp. 80–159) notes that one should seek the roots of an armed conflict in the nature of the state (including the political systems of states, the nature and structure of society), also taking into account such factors as history and the political and strategic culture. The causes of conflicts lie in the malfunction of political and economic systems including differences in the level of economic development between states.

This problem of the causes of armed conflicts has already been raised by ancient theorists. Platon (1958, p. 111) claimed that the generation of conflicts is caused by a violation of human integrity, as well as the failure of individuals and society to observe moral norms. The sense of injustice is a result of this situation. It accompanies the arousing insatiable desires, which consequently manifest themselves in individual attempts to dominate others as well as states seeking dominance over other states. He also says that conflicts result from the ‘natural hostility of tribes’ (states) and overpopulation in states. The overpopulation problem was elaborated on more widely by Malthus (2008), who claimed that factors such as birth rate and population have a decisive influence on the development of society and the emergence of armed conflicts. The main cause of conflict is the irreconcilability of natural growth with the capacity to provide an adequate minimum of means of subsistence for a rapidly growing population.

Horwitz (2000, pp. 95–100), in turn, notes that ethnicity is a factor in conflicts in society, in particular in heterogeneous society. Ethnicity determines the principles of the group’s functioning, creates a framework for its separateness based on emphasising its autonomy in language, culture, ideology and history. Violations of these principles by members of another group, often referred to as ‘the other’, pose a threat to the existence of the members of an ethnic group. The same reaction arises when there is a threat of changing the status quo of an ethnic group through the political activity of the state. The response to the threat is often aggressive and radical actions carried out by the vulnerable-attacked ethnic group, often leading to the outbreak of an armed conflict.

What is more, Kaufman (1996, pp. 149–171) points out that the security dilemma is also the cause of conflict. It manifests itself in the lack of a sense of security among the members of the group, which may arise when the threat to one group from another is real or the threat depends exclusively on imagining the other group as an enemy. A threat is defined through indicating the most characteristic or representative features, which leads to polarisation of the perception of the situation. When these characteristics are identified (by this group or by opponents), the situation begins to be perceived by the parties as bipolar. This then takes on the character of a classic zero-sum game, in which one side winning entails the other side losing.

Furthermore, Dziewulska (2007, pp. 58–63) emphasised that the security dilemma does not always have to be generated by physical threats to the group. It can be initiated by the appearance of a threat to the status of a group, its value, role, and position in society. The security dilemma triggers a self-perpetuating mechanism of violence, which takes the form of retaliatory action. Moreover, it is used by the elites of ethnic groups as a tool to mobilise members of the group to gain their support, gain power, start or prolong the conflict. In order to influence the group, leaders refer in communication with its members to a perception of the group as ‘their own’ and ‘extended family’. They strengthen the impression of an increasing security threat, which means that even a minor incident can trigger conflict with the ‘others’ – the hostile group perceived as an aggressor.

Another type of conflict at the level of social groups, which also needs to be mentioned, is a conflict between civilisations. Huntington (1993, pp. 23–25, 35–39) defines civilisations as large cultural units that are characterised by various value systems resulting from religious and cultural differences arising over the centuries. These differences are more difficult to reconcile than political or economic differences. He argues that the source of a conflict is a clash of civilisations, as the boundaries of individual civilisations generate conflict. Major clashes occur between Western and Muslim, Muslim and Hindu civilisations, as well as Hindu and Chinese civilisations. The confrontation takes place on two levels, i.e. the micro-level (neighbouring groups fight for territory, e.g. the war in Bosnia) and the macro-level (groups of countries belonging to different civilisations fight for military power, control of international institutions, promotion of their religion and culture). Dougherty and Pfaltzgraff (2001, p. 167) argue that in the present day, the factors which intensify the growing conflicts between civilisations are religious differences, increasing interactions within civilisations, globalisation and the growth of economic regionalism, weakening the function of the nation state as the basis for group identification, with the resulting gap being filled by increasing awareness of belonging to a religious group. Smuniewski (2016, p. 438) also emphasised that fundamentalism and extremism are the conflict-generating factors in a civilisation. In the Western civilisation, actions taken to eliminate these factors are characterised by ‘a tendency to marginalised values, diminish the role of man by subordinating him to society, marginalising religion in all attempts to separate it from social and shared life’. On top of this, it is necessary to mention that one of the most serious consequences of an ethnic conflict is forced migration. It has recently become a challenge to global security which is being addressed mostly by the European Union and the Member States by developing migration policies and regulations of asylum matters (Domalewska and Żakowska 2019, p. 208).

The roots of armed conflicts can also be found in the political systems of states, regardless of whether these are democratic, authoritarian or totalitarian. According to democratic peace theory, liberal democracies do not wage war on each other (Doyle, 1986, pp. 1151– 1163; Czaputowicz, 2011, p. 84). To support this thesis, two types of argument were put forward: institutional and normative. The institutional argument explains that the system in every country should be republican, i.e. ensuring freedom and equality for all citizens.

Because mechanisms regulating social and political relations in such a system (established base on tripartite separation of power, transparency in the operation of state administration, political pluralism, freedom of expression of public opinion, including free media, public debate regarding the justification for military intervention) limits the possibility of belligerent intentions of governments occurring, especially during an election period.

The normative argument refers to the Kantian concept of a federation of democratic states. It implies that the norms, culture and standards of behaviour existing within the state are transferred to the sphere of international relations. For this reason, democratic states tend to be peaceful and have a positive view of other democracies. They resolve crisis situations through negotiations while striving to preserve the existing status quo. They assume that other democracies apply the same standards of conduct. This conviction is reinforced by positive experiences of mutual cooperation between democratic states. Unlike democratic states, authoritarian states and dictatorships are more aggressive, because they do not have institutional or normative restrictions in political and social life. Thus, democratic states will wage wars with non-democratic neighbouring states in order to change their system to a democratic one and thus ensure their own security in the region (Czaputowicz, 2011, pp. 84–86). Owen (1994, p. 92) explained the validity of these arguments as follows: liberal ideology motivates some citizens against war with a similar democracy, and democratic institutions allow this ideology to affect foreign policy.

Nye (2007, pp. 48–49), in contrast, noted that the assumptions of democratic peace theory may not be consistent for different types of democracy. This argument refers to countries in the early stages of democratic transition (the so-called ‘new democracies’). An example would be the unstable democracies in Ecuador or Peru, as well as in the countries of the former Yugoslavia, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina. Therefore, the nature of democracy is important when it comes to initiating armed conflicts. However, the progressive increase in the number of stable democracies worldwide may reduce the likelihood of the outbreak of armed conflict.

The level of the international system

Waltz (2001, pp. 159–224) notes that armed conflicts are generated by the nature of the international system, where the conflict-causing factor is its anarchic nature, which compels states to fight for their survival. Anarchy is a force that shapes and limits the actions of states and affects the way the international system functions as the distribution of capabilities among players varies over time. Its occurrence causes the war to be perceived as a normal phenomenon in the system.

According to the assumptions of the balance of power theory, in an anarchic international system in which there is no world government that could prevent states from exploiting each other, states fear conquest, aggression – annexation and extinction by force (Sheehan, 1996). Therefore, they seek to avoid the hegemony of other states and to preserve their independence. The main goal of their activities is to maintain an equal level of power among major states and their allies. In this situation it is less important whether the system is uni-polar, bipolar, tripolar, or multipolar because the balance of power means peace is preserved through deterrence of any power that might become an aggressor. An important condition for the maintenance of the proper balance is that the military capabilities of states are stable and measurable. The technological changes in the military sphere have a destabilising influence on the equality of power in the system. They create an opportunity for one state (or group of states) to use the preponderance it has before the technology spreads and encourages an arms race. This builds uncertainty among states regarding the real power of other members of the international system (Levy, 2004, pp. 29–52). In order to secure peace, states make countries displaying aggressive aspirations aware that expansion will be met with coalition forces confrontation. Therefore, they take various forms of action to prevent the emergence of a state (or group of states) preponderances in the international environment e.g. forge alliances and arm. The central purpose of those efforts remains to protect weak states from aggression by strong ones. This way the maintenance of equal capacities between the major powers is considered an effective deterrent to war.

In turn, power transition theory indicates that the main cause of war is the change in the relationship between powers in the international system as a result of the size and rates of growth of the participants in the system, which makes it possible to be ahead of the leader state and take its position (Kugler and Organski, 1989, p.176; Tammen and Kugler, 2000, pp. 6–10). In this case, as Cashman (2014, pp. 411–414) points out, the international system is less anarchic but more hierarchically organised. The dominant states and leaders which operate within them create the rules and norms for this system regarding trade, diplomacy, the use of force, etc. The leader occupies the main position in the system and leads the so-called ‘satisfied states’, which form a coalition supporting the leader and have great influence on preserving the status-quo of the system. A power transition occurs when the challenger states achieve relative parity with the dominant states. This situation opens a range of opportunities for the rising power (challenger) and creates a wide area of vulnerability for the declining leader. War may break out when the challenger is dissatisfied with the world order established by the global leader, the existing status quo or his position in the system, and therefore wish to revise the rules of that system to better suit his own interests. Then, the parity provides the opportunity for war and the dissatisfaction provides the willingness. Ultimately, dissatisfaction with the status quo is an essential precondition for conflict. Satisfied states do not start wars because they are the primary beneficiaries of the present system and do not have an interest in changing it. In the other scenario, war most likely occurs when the power distribution between the dominant state and the challenger is approximately equal. The challenger would be most likely to initiate war before equality is actually attained due to the following: a) rapid growth which produces overconfidence or frustration and impatience over how the demands for changes to the international order are not accommodated, b) a tempting opportunity arises that can be used to achieve a total and unambiguous victory. Dominant (and declining) states may also initiate wars to eliminate threats from rising challengers before the power transition is achieved (this is an example of the preventive use of force). In this situation, the challenger has a strong reason to postpone the employment of force until surpassing the dominant power provides him with a greater chance to win. According to Organski (1968, p. 376), the risk of the outbreak of war appears when the following determinants appear: the development of the rising state is fast, and its power is similar to the power of the dominant state; the absence of a tradition of cooperation between the states; and revisionist state attempts to change and replace the existing international order with its own order. Cashman (2014, p. 414) extends the list of factors, indicating the following: existence of rough parity; the challenger’s level of dissatisfaction with the status quo; the existence of a risk-acceptant rising challenger and risk-averse declining state; and the low costs of war. Additionally, Gryz (2011, p. 7) noted that in the modern globalised world, such factors as social barriers (lack of legitimacy to act or implement political policy), instability of economic systems (associated with the flow of funds and their allocation); failure to adopt measures to political, economic, military and instructional situations; and the lack of skills and qualifications to assess the situation in the context of international (and national) relations should also be taken into account.

The roots of armed conflicts in the international system are also explained by the theory of hegemonic war. The reason for war is a direct contest between the dominant power(s) and a rising challenger over the governance and leadership of the international system. Gilpin (1998, pp. 591, 601–602) states that the uneven growth of power among states is the driving force of international relations and leads to the changing distribution of power among the states within the international system. In this situation, the elements of the system, e.g. the hierarchy, the division of territory and the international economy are not entirely consistent with the changes in the distribution of power among the major states within the system.

The system is characterised by a hierarchical ordering of the states in the system with dominant or hegemonic power. The leader state (called the hegemon) relies on its simultaneous military and economic dominance and on its ability to provide certain public goods to the participants in the system, which include military security, investment capital, international currency, a secure environment for trade and investment, a set of rules for economic transactions and the protection of property rights, and the general maintenance of the status quo. In exchange for such mutual goods, the hegemon receives revenue and other benefits. Over time, the power of subordinate states begins to grow disproportionately. The satisfied states do not start wars because they are the primary beneficiaries of the present system and do not have an interest in changing the growth of their relative power. The rising states try to introduce changes to the rules of the system, the manner in which spheres of influence are divided, and the manner in which benefits and territories are distributed but only when the expected benefits of altering the system are predicted to exceed the expected costs. As the rising power develops, it comes into conflict with the dominant or hegemonic state in the system. The ensuing struggle between these two states and their respective allies leads to a bipolarisation of the system, which cause the increasing instability of the system. In this case, a minor event may spark a crisis, and finally cause a hegemonic war (Gilpin, 1998, p. 592; Cashman, 2014, p. 429). The clash between powers is based on power struggle (including strategic and national interest), not economic struggle. Disequilibrium (uneven growth) arises mainly due to changes in military technology and strategy, and secondarily to changes in transportation, communication, industrial technology, population, prices, and the accumulation of capital.

War occurs when the reigning hegemonic state gradually loses its superior economic and military position and then the hierarchy of prestige in the system and the hierarchy of power are no longer compatible. The presence of some factors also causes the decline in the relative position of the hegemon, which is virtually inevitable:

the costs of maintaining dominance in the system (including military expenditure, aid to allies, and provision of the mutual economic goods necessary to maintain the global economy);

unequal growth rates that lead to states other than the hegemon assuming economic and technological leadership, a decline in innovation and risk tending towards greater consumption and lower investment in the hegemonic state;

the tendency of military and economic technology to diffuse to other states;

the erosion of the hegemon’s resource base;

the tendency for power to shift from the centre to the periphery as adjustments among states in the central system weaken them all (Cashman, 2014, p. 428).

It is difficult to ultimately determine who initiates the war. On the one hand, it is believed that it is the rising challenger which is expected to be the most likely initiator of war because it attempts to expand its influence up to the limit of its new capabilities. On the other hand, it is possible that the hegemon itself may attempt to weaken or destroy the challenger by initiating a preventive war to avert its loss of position. In the consequences of hegemonic war, the system is ready for fundamental transformation because of profound changes in the international distribution of power, social relations, economic organisation, and military technology. These upheavals undermine both the international and domestic status quo, and cause shifts in the nature and locus of power. The end result of hegemonic war is the emergence of a new equilibrium with a new distribution of power, and the beginning of a next growth-expansion-decline cycle.

Discussion

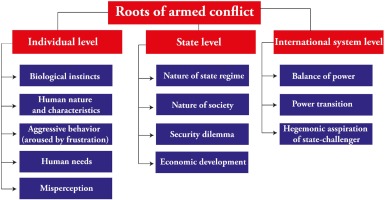

Based on the review of theoretical approaches, two matters are proposed for future discussion. The first one is the systematisation of the roots of armed conflict (see Figure 1). It needs to be emphasised that this concept does not cover all the factors that cause a conflict. This limitation therefore leaves an opportunity for further research of in this field.

Moreover, the conducted research raises a question: Which analytical approach should be taken into consideration in the process of identifying the roots of modern armed conflicts? The literature review shows that scholars most often tend to choose a comprehensive approach when researching the roots of modern armed conflicts, i.e. searching in parallel on all three analytical levels - the individual, the state and the political system. For instance, Nye (2007, pp. 48–49) considers this choice as the most appropriate due to the fact that it is difficult to unequivocally answer the question of who or what has the decisive influence on the outbreak of war, whether it be an individual, a state or the structure of the international system. Franks (2006, p. 85) similarly suggests adopting this comprehensive, multilevel and multi-dimensional perspective. He believes that this allows a broader understanding of the causes, particularly identification of deep-rooted causes.

On the one hand, the applied comprehensive approach allows for a broad understanding of the causes of conflicts, but also introduces the risk of a superficial understanding, omitting elements relevant to the specific nature of the causes. In order to avoid this, it is suggested to select the core-leading approach (or approaches) – the primary one and treating the others as the supplementary (complementary function). There are two main factors to consider when choosing an approach: the actors involved in the conflict (warring parties) and the nature of the conflict. Regarding the actors, it is imperative to pay attention to the type of actors and their influence on the conflict generation and its dynamics. For instance, the internal actors initiating the conflict remain in direct relation to the causes of the conflict. This link is visible in the way they define their goals, interests, strategies and measures in a conflict. The involvement of external actors introduces a new variable into the ongoing conflict, which results in a change in its environment, form, and dynamics. External actors bring in an individual bundle of objectives and interests that are not necessarily in line with those of the warring parties. Their participation in the conflict may be an action aimed at prolonging the duration of the war, as it provides them with particular political and economic benefits. The interests of external actors may therefore modify the perception of the roots of conflicts or even create a new catalogue of them.

Regarding the nature (type) of a conflict, on the basis of the methodology elaborated by UPPSALA Department of Peace and Conflict Research as part of The Uppsala Conflict Data Program, as well as Łoś and Regina-Zacharski (2010, pp. 65–84) and Żurawski vel Grajewski (2012, pp. 47–63), the need for an analysis of the roots of most common contemporary conflicts can be seen, namely the inter-state conflicts, intra-state conflicts, non-state conflicts, internationalised conflicts, and modern hybrid war.

In the case of inter-state conflicts, the main level analysis of causes chosen should be the state level approach, considering the type of conflict in which the states are the main actors (‘players’). The level of the individual and the international system approach is viewed as an important, but secondary effort. It is more difficult to identify the cause in intra-state conflicts and non-state conflicts due to the diversity of actors, the problem of definition of their roles, goals and interests, and the nature of relations between the individual and a social group. In these conditions, in the intra-state conflicts, the analysis should be focused on the state level and the individual level causes, when identifying roots at the international system level is understood as complementary action. In the case of non-state conflicts, we should be looking for roots of the conflict as primary on the individual level and the international system level and supplementary on the state level. With regard to internationalised conflicts, which are notable for a broad diversity of actors participating in the war and highly unpredictable dynamics, the examination of the causes of a conflict requires an analysis at primary, individual and state level and as supplementary - the international system level. The selection of an approach to analysing the causes of modern hybrid war is the most challenging. The main problems are the difficulty in clearly identifying the parties to the conflict, their goals and interests, as well as the high unpredictability of its dynamics due to the possibility of conducting operations in various areas using diverse methods (Vuković, Matika and Barić, 2016, pp. 118–138). This type of war opens a wide window for a discussion about the appropriate analytical perspective for seeking causes. However, the examination of hybrid conflict in Ukraine (2014-present) leads to suggestion for identifying the roots of conflict as primary on the state level, and as supplementary on the level of the individual and international system. A proposal to systematise approaches for identifying the roots of modern armed conflicts appears below (Table 1).

Table 1

The systematisation of approaches to identifying the roots of modern armed conflicts

Conclusions

The roots of armed conflict are factors of a very diverse nature that constitute the grounds for the conflict and result in challenges to the existing relationships, norms and rules, and decisions in the process of policymaking of conflict parties (internal actors) as well as actors participating in the conflict (external actors). They lead to the rise of differences in mutual perception of the parties/actors as well as their recognition and judgment of events, assets, security, or equality. Moreover, they are the foundation on which the divisions of society and the measures to define the object of disputes are built.

The result of this research allows the main factors-roots of the conflict to be systematised. At the level of the individual, the causes can be seen in human nature and characteristics, biological instincts, aggressive behaviour (aroused by frustration), misperception and failure to satisfy primary basic needs. At the level of the state (and society), they are found in the state regime’s nature (e.g. autocratic regimes, early stage democracies). Relative to stable democratic states, authoritarian states are more aggressive in their efforts to start wars because they do not have the mechanisms regulating social and political relations within their administrative structures, which limit the intentions for war of democratic governments. Regarding the nature of society, a conflict is generated by ethnic diversity. A heterogeneous society is more susceptible to trigger mechanisms of a security dilemma and mass manipulation compared to a homogeneous society. War is also triggered by differences in economic development, a particular appearance of a contradiction between diversity rates of economic increment and the ability to provide a livelihood for a rapidly growing population. At the level of the international system, generally its anarchic nature generates armed conflicts. More precisely, war arises as a result of the state’s security dilemma caused by the imbalance of power between major states (and their allies) and other state members of the system. The source of the conflict is the phenomenon of power transition that has arisen as a result of a rising power challenging the position of the dominant state (the so-called challenger) due to the dissatisfaction of its position in the system, established world order or the existing status quo. This action is mostly motivated by the economic growth of the challenger. Moreover, armed conflicts are also caused by the state’s aspiration to assume the position of the leader-hegemon in the international system which leads to direct contests between the dominant power(s) and a rising challenger, so-called hegemonic wars.

A detailed analysis of the roots of conflict may help with the development of the terms of peace agreements which could be voluntarily accepted and implemented by the parties to the conflict (internal actors). Therefore, understanding the roots of conflict is closely linked to the termination of outgoing modern wars and prevention of the outbreak of new wars. Consequently, further research is required to establish an appropriate approach for a roots of conflict analysis. It is strongly recommended to consider introducing diversification on the primary and supplementary level of analysis, while paying attention to the factors e.g. actors to the conflict and nature of the conflict.