Introduction

Following the events in Ukraine in 2014, when the Russian Federation annexed Crimea and conducted hybrid military activities in the Lugansk and Donetsk regions, the three Baltic states (3B), like most of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) states located on the eastern NATO border, felt threatened. As the Russian threat continued to mount, the Warsaw Summit held in 2016 decided to establish an enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) in 3B and Poland to act as a “tripwire” enabled to trigger a collective NATO response (NATO Defense College [NDC], 2019). As aggressive Russian military activity continued, culminating in a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, NATO immediately reacted by reinforcing existing eFPs and subsequently, at the Madrid Summit, agreed to establish additional eFPs in Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia (North Atlantic Treaty Organization [NATO], 2023), and to upscale all eFPs to a brigade-size unit if need arises (NATO, 2022a).

More intensive cooperation amongst NATO states, particularly between the eFP host nation (HN) and framework nation (FN), occurred due to the security situation in NATO’s neighbourhood and the decision on eFP. It remains to be seen whether the eFP setting will strengthen the existing, and create new, venues of mutually beneficial bilateral cooperation. Establishing similar eFPs in other NATO countries would require familiarisation with the 3B case as it would enable a better HN and FN nexus that would lead to higher synergy.

The study aims to examine the nexus between HN and FN in the eFP framework in 3B while referencing small state theories. The research object is the nexus seen from a small state’s perspective between the HN and FN. The study seeks to answer whether: (1) theories of international relations (IR) are capable of explaining the behaviour of 3B (R1) in the eFP framework; and (2) small states can balance medium powers (R2). The study does not seek to suggest improvement of any IR theory and aims to highlight the most suitable theory in explaining the FN–HN nexus in 3B.

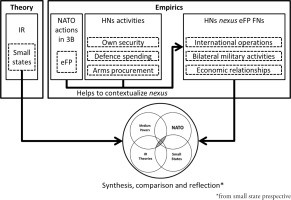

The analysis timeframe is 2014–2023 and is limited to empirical data from interstate military and economic cooperation. Comparative qualitative and quantitative, primary and secondary data, and historical analyses were applied with the congruence method in the study through the logic research design (Figure 1). The most relevant secondary data was chosen using Google Scholar and Google Search tools whereas primary data came from national statistical offices, government ministries, and agencies.

The research explores the nexus among 3B from the perspective of small states acting as HN and medium powers acting as FN in the larger NATO format. In addition to the military activities in the NATO context, HNs and FNs enhance their bilateral cooperation in multiple areas. Besides empirical analysis, which forms the core of the study, the theoretical part highlights the existing IR theories and seeks to indicate the one that would better explain the phenomenon of forming the HN-FN nexus from a small state perspective. As this is not a single-country case, studying multiple countries under similar conditions helps to explore the topic better.

The nexus between HN and FN in the eFP context is analysed in such detail and scope for the first time. Prior to this, the study by Palavenis (2023) encompassed only German and Lithuanian inter-relations in the eFP context and concluded that Germany had its rationale for choosing the FN role in the eFP mission in Lithuania. Most authors that analysed eFP have not contemplated nexus and its relevance to small state theories, and their relevant studies could be grouped into at least four distinguishable areas of interest. Firstly, some authors considered eFP inception, concept, and implementation effectiveness. In this field, Zapfe (2016) focused on the necessity of the eFP and NATO’s response options (Zapfe, 2017). Stoicescu and Järvenpää (2019) analysed NATO’s decision on eFP deployment. Luik and Praks (2017) examined the eFP concept and highlighted implications for the region. Rácz (2018) concluded that eFP influenced the strategic balance in the Baltic Sea region and changed Moscow’s calculations. Marian (2023) focused on the threats and opportunities that the eFP concept presents. Lanoszka and Hunzeker (2023) assessed the adaptation of eFP throughout 2017–2022 whereas Mälksoo (2024) analysed political rationalities, historical analogies, and practical implementation details similar to eFP constructs. The second group of articles focus on threat assessment; in that regard, McKay (2017) considered economic growth, energy security, and ethnic Russians’ potential to affect the correlation of forces in 3B. Kristek (2017) focused on the threat aspect of NATO’s eFP in 3B. The third group of researchers is oriented into single-country cases, like Šešelgytė’s (2020) research that looked at Lithuanian security concerns from the HN perspective. Leuprecht and Sokolsky (2017) explained the Canadian rationale for leading eFP in Latvia, and Matlé (2023) discussed an increasing German role and its military adoption in the context of eFP. The last group of articles is devoted to assessing cooperation, and on this subject, Christian Leuprecht concluded that the eFP improved security cooperation among member states deploying troops (NDC, 2019).

On the theory side, the study considers the most recent IR scholars’ works on the small states that could relate to the eFP case study.

The study is structured into three parts. The first part examines the existing IR theories that explain small state behaviour. The second part is devoted to empirics and starts with an explanation of eFP, followed by analyses of HN’s contributions to state security and a look into bilateral cooperation venues. The third part is devoted to a discussion, focusing on the FN–HN nexus elements derived from the theoretical and empirical parts.

Small State Behaviour According to International Relations Theories

Definition of the small state

The definition of a small state still needs to be fully resolved, as there are many disagreements in this area. Firstly, there is no consensus on the definition of the particular quantitative factors, that is land area, population size, gross domestic product (GDP), and military expenditure (Demir, 2008, p. 141) that could be associated with a small state. Complex quantitative formulas are created to consider multiple variables, including other aspects such as perceptual or psychological (Willis, 2021, p. 21). However, it is noted that different contexts favour different variables (Thorhallsson and Wivel, 2006, p. 659). Furthermore, challenges arise if states belong to a “microstate” or “middle power,” as their measurable parameters are similar (Baldacchino and Wivelm, 2020, p. 13). Secondly, the number of small states is changing as their indicative factors evolve. Thirdly, only recently have small states been recognised by some mainstream IR theories as not marginal actors (Willis, 2021, p. 22).

Challenges arising for small states

Small states face challenges similar to those faced by other states in the international arena; however, their reactive options are more predictive and narrow once “national interests of the bigger powers are at stake” (Urbelis, 2015, p. 65). Contemporary threat, such as direct invasion, cyber-attacks, hybrid warfare, natural disasters, propaganda, terrorism, and refugee crises, put pressure on small states to seek viable options to compensate for their weaknesses in the number of inhabitants, market size, smaller economy and territory, and military capabilities (Thorhallsson, 2019, p. 382). Small states can mobilise fewer troops, invest less in novel military technologies, and cannot sustain longer military campaigns (Thorhallsson and Steinsson, 2017, p. 58). However, small states can minimise risks by “adopting particular domestic or external measures,” such as good economic and administrative management (Thorhallsson, 2019, p. 383), capable and active representativeness (Weiss, 2019, p. 195), providing HN support for foreign troops (Dvorak and Pernica, 2021, p. 170), and gaining expertise in a particular niche sector.

Small states have certain flexibility if the issue is less relevant to more powerful states (Urbelis, 2015, p. 76); they could receive assistance from great powers if inaction is seen as dangerous or they need support. Once a small state is a member of an international institution, this allows it to have a more prominent voice when compared to its size, and additionally, creates more opportunities for bargaining (Baldacchino and Wivel, 2020, p. 12). However, this requires more diplomatic and administrative resources (Thorhallsson and Steinsson, 2017, p. 60) and may lead to a situation that contradicts domestic policies (Weiss, 2019, p. 199).

Prevailing small state theories

The small states are seen differently depending on dominant IR theories that have developed over time, for instance the first wave (1959–1979) can be related to the primary tenets of classical realism, the second wave (1979–1992) can be aligned with the theory of neorealism, and the third wave (1992–present) can be aligned with the constructivist school of thought (Willis, 2021, p. 20). The study considers all IR theoretical paradigms in modest detail, focusing on alliance and alliance shelter theories that presumably better explain the nexus.

Through the lens of classical realism, small states are assessed as lacking power and, therefore, having no significant impact on the international system (Willis, 2021, p. 21). However, small states could seek non-material gains, such as a “loyal ally” reputation (Pedersen, 2020, p. 43), have less room for manoeuvre on an integrational agenda (Handel, 2016, p. 31), and can become satellites of a greater state (Galal, 2020, p. 41).

In the neorealist view, small states could still bargain on essential issues whilst using their relative power (Willis, 2021, p. 19), which lies in natural resources, geographical location, and the international structures they are part of (Urbelis, 2015, p. 79).

Constructivists explore prestige as a central driver for small state motivation acting within international structures. Small states receive territorial protection and closer “relationships with the alliance hegemon” in NATO (Pedersen, 2020, p. 44) and remain positive towards the European Union (EU) (Thorhallsson and Wivel, 2006, p. 658).

According to liberal theory, small states are more interested in developing international institutions due to their apparent vulnerability and behaviour, shaped by factors like the country’s economic sectors and political influence (Thorhallsson and Wivel, 2006, p. 657).

In neoliberal theory, small states can use their “soft power to appeal to common values” while acting in NATO, where the most potent members cannot unilaterally impose their will (Urbelis, 2015, p. 83).

Shelter theory explains the situation where small states need specific shelter (political, economic, and societal) provided by larger states or international organisations (Thorhallsson, 2019, p. 390). All options inevitably give up some sovereignty in exchange for enhanced prospects for survival and prosperity (Thorhallsson and Steinsson, 2017, p. 86).

States can enter into alliances to supplement each other’s capabilities, thus reducing the impact of a potential opponent’s actions (Bailes et al., 2016, p. 17). States could enter an alliance not only for security but also for reasons of influence. The primary motivation for small states to join alliances is the recognition that they must act together to remain visible in the international arena (Urbelis, 2015, p. 85). It is believed that small states tend to align with the weaker of two sides to oppose emerging threats. As a result, being on the weaker side, states feel more appreciated (Bailes et al., 2016, p. 16). An alliance can reduce defence burdens by pooling and sharing scarce resources and can avoid duplication in the drive to develop mutually beneficial capabilities (Thorhallsson and Steinsson, 2017, p. 119).

Alliance shelter theory focuses on ethnicity, demographics, regime type/ideology, and economic and threat patterns. This contrasts with the shelter theory, as it captures the complexities of small state alliance foreign policy behaviour (Bailes et al., 2016, p. 22). As small states have domestic factors that shape different parameters of the shelter relationship, mutually beneficial cooperation could be based on other factors besides the power calculation. Shelter alliance could affect small states’ social and political developments; the small state relationship is “neither based solely on subordination or annexation nor on equality or autonomy” (Vaicekauskaitė, 2017, p. 10).

Free-riding theory explains when the smaller allies exploit the major powers without paying their fair share (Plümper and Neumayer, 2015, p. 258). However, small states tend to stop free-riding once they perceive an increased threat, their economic situation is improving, or they are pressured by the hegemon (Dvorak and Pernica, 2021, p. 170).

Balancing is directed towards the threat, and offensive or defensive bandwagoning could occur. Offensive bandwagoning aims to share in the spoils. In contrast, defensive bandwagoning aims to influence the winner to refrain from attacking (Bailes et al., 2016, p. 20). Bandwagoning is seen as a way for small states to survive by accepting the will of a powerful aggressor, rather than opposing it (Thorhallsson and Steinsson, 2017, p. 138).

Small states prefer hedging because it is less provocative, counterproductive, and risky regarding political and economic gains (Vaicekauskaitė, 2017, p. 12). Hedging strategies include indirect balancing, dominance denial, economic pragmatism, binding engagement, and limited bandwagoning, which are employed to achieve specific aims (Cheng-Chwee, 2008, p. 162).

A policy of neutrality could ensure small states’ sovereignty (Vaicekauskaitė, 2017, p. 15), although a state’s survival depends on its “ability to demonstrate that it is truly neutral and a non-threat to larger states” (Thorhallsson and Steinsson, 2017, p. 123).

Strategies employed by small states in contemporary geopolitics

Each theory indicates tendencies and potential regularities (Table 1) that could be associated with a particular state’s behaviour.

Table 1

Theories and concepts explaining small states’ behaviour.

Small states’ choices are influenced by multiple external and internal factors, including the location of the great power, the tension between great powers, the relationship history, intergovernmental institutions, regional collaboration, economic factors, good governance, and political stability (Thorhallsson and Wivel, 2006, p. 659). In broad terms, there are two wide patterns of foreign-policy behaviour for small states. They can either keep their autonomy and stay neutral, or use cooperative schemes such as bandwagoning with major powers, forming alliances against dominant powers, seeking shelter, or using hedging strategies.

The Rise of eFP, HNs’ Attitude to Security, and Bilateral Cooperation with FNs

NATO’s initiatives to support the security of 3B

Following the events in Ukraine in 2014 and 2022, multiple NATO decisions were made to increase security in 3B, which are geographically exposed.

eFP: The growth from battalion to brigade

In a significant move, the decision to establish eFPs in 3B and Poland was taken in 2016 (NATO, 2016), a time when member states were sharply divided over renewing dialogue with Russia (NDC, 2019).

At the Wales Summit of 2014, NATO did not agree to any combat troop deployment options to NATO’s east. As Russia continued its military activities in Ukraine and started the campaign in Syria, it became clear that the risks for 3B were increasing, and the already deployed USA military contingent was too small for deterrence (Stoicescu and Järvenpää, 2019, p. 18).

The initially deployed eFPs in 3B consist of three battlegroups, comprising troops from several NATO member states (Table 2) and led by an FN (Zima, 2021, p. 4). The FN provides the core of the battlegroup combat-ready troops and equipment (NDC, 2019).

Table 2

NATO countries participating in eFPs located in 3B (NATO, 2022b; Stoicescu and Järvenpää, 2019, p. 16)

From January to April 2017, the first eFP contingents were deployed to 3B. The contingents gradually integrated with the USA infantry companies and became an integral part of HNs’ land forces. The eFPs operate with multinational contingents that rotate regularly, ensuring 24/7 combat readiness. They maintain a clear command and control relationship, being subordinated through regional divisional and corps headquarters (Stoicescu and Järvenpää, 2019, p. 15).

At the heart of its mission, the eFP task plays a pivotal role within “NATO’s wider strategy of deterrence by denial and punishment” (Stoicescu and Järvenpää, 2019, p. 12). eFP could be seen as the “latest manifestation of pragmatic NATO adaptation, precipitated by Russian aggression” (Hadfield, 2018, p. 43) and designed to make Russian adventurism into 3B costly and less attractive.

Following a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and decisions made at the Madrid Summit, NATO reconfigured its defence strategy on its eastern flank. It established the NATO-enhanced vigilance activity (exercising rapid deployments to increase eFPs to brigade-size units and conduct military exercises) and four new battlegroups in Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, and Bulgaria (Mälksoo, 2024, p. 541). This signifies NATO’s conceptual shift from “forward presence” to “forward defence” (Matlé, 2023, p. 4).

Other NATO initiatives in the region

There were multiple NATO initiatives to enhance security in 3B in terms of “allied ground, air and maritime presence on NATO’s north-eastern flank.” The eFP comprises almost half of the overall NATO troops in 3B (Stoicescu and Järvenpää, 2019, p. 15). At the Wales Summit, members pledged to spend more on their militaries (Lanoszka et al., 2020, p. 10); NATO’s Readiness Action Plan was adopted, which included creating a NATO Response Force (NRF) three times larger than the current size, and the rapidly deployable Very High Readiness Joint Task Force; Multinational Corps North East in Szczecin. NATO Force Integration Units (NFIU) were established in Central and Eastern Europe; and more NATO exercises in 3B were announced, with additional surveillance flights and maritime patrols executed (Friede, 2022, p. 529).

The Baltic air policing mission (BAP) that was initially performed only from Šiauliai air base in Lithuania has been reinforced by additional aircraft operating from Ämari air base in Estonia (Stoicescu and Järvenpää, 2019, p. 13). NATO’s early airborne warning and control force raised the number of overflight missions over 3B (Lanoszka et al., 2020, p. 10). In the maritime domain, the standing NATO maritime and mine countermeasures groups intensified their operations in the North and Baltic seas (Stoicescu and Järvenpää, 2019, p. 15).

Since 2014, multiple NATO centres of excellence (CoE) have been set up in the Baltic Sea region, focusing on counterintelligence (Poland), strategic communications (Latvia), and hybrid threats (Finland) (Friede, 2022, p. 531).

In the post-2014 period, there has been an increase in the “number and scope of NATO military exercises related to the air defence of 3B’s.” In 2016, 3B and NATO signed an agreement on airspace management supporting the BAP. Furthermore, 3B cover all HN support costs for BAP (Cieślak, 2021, p. 17).

During the NATO summit in Brussels in 2018, the NATO readiness initiative, the so-called “Four Thirties,” was announced. This initiative saw the pooling of the existing NRF forces and the availability of an additional thirty heavy or medium manoeuvre battalions, thirty major naval ships, and thirty air squadrons for deployment in battle within 30 days (Blankenship and Lin-Greenberg, 2022, p. 108).

Region-wise, Finland (in 2023) and Sweden (in 2024) became NATO members, thus creating increased security in the Baltic Sea region (Mälksoo, 2024, p. 542).

HNs’ activities to ensure greater security, venues for cooperation

The 3B recognised the fragility of their sovereignty and the importance of national defences. As a result, fundamental changes were made to enhance preparedness for state defence, including increased defence budgets (Table 3).

Table 3

3B Defence spending in 2014–2023 (NATO, 2024, p. 6).

Estonia was the only state from 3B that spent around 2% of GDP on defence prior to the Russian aggression whereas Latvia and Lithuania were not in line with NATO’s recommendation on defence spending. However, in the face of potential threats, both countries managed to increase spending in a comparatively short period.

A substantial defence budget was spent on acquiring new armaments (Table 4) and facilitating internal reorganisations.

Table 4

Overview of acquired major armaments by 3B in the 2014–2023 period (SIPRI, 2024).

In 3B, various modernisation programmes were launched “focusing on rebuilding the combat and crisis readiness of the land forces, strengthening intelligence and surveillance capabilities, air and missile defences.” Particular focus was given to increasing combat capabilities whilst providing HN support for the USA and NATO initiatives (Friede, 2022, p. 530).

While the 3B reacted efficiently, the focus differed across the region. Lithuania could be seen as “a new defence policy leader amongst the 3B,” as it has the most significant defence budget and acquires the most equipment (Dvorak and Pernica, 2021, p. 171). Estonia focused on “territorial defence, compulsory military service, a large reserve army” and on the cyber domain where a “separate cyber defence command” was established. Latvia focused more on out-of-area international missions and operations (Nikers and Tabuns, 2022, p. 50).

Parallel to military forces, paramilitary voluntary defence organisations gained renewed importance in the 3B. For example, the Latvian National Guard was provided with the necessary funds and established new force elements to cover more expansive areas, increased readiness mechanisms, modernised training areas and infrastructure, and procured extra equipment (Friede, 2022, p. 532).

Regarding the conscription base, Lithuania reintroduced conscription in 2015 and gradually expanded whereas Estonia chose to continue with a conscript-based system and increased the number of new conscripts. Latvia decided on voluntary conscription in 2023 (Lithuanian Radio and Television [LRT], 2022).

Strengthening air defences was considered a priority for 3B; therefore, 3B acquired different short-range air defence systems. Lithuania acquired a medium-range surface-to-air missile system (Cieślak, 2021, p. 18).

Still, more defence synchronisation activities need to be implemented amongst the 3B, including developing maritime and air defences, joint procurements, maintenance of military equipment (Nikers and Tabuns, 2022, p. 52), acquisition, and external support. Nevertheless, there are positive signs of practical cooperation in cyber security and other areas (Horchakova, 2022, p. 97).

HNs attitude towards eFP FNs

eFPs contribute to “deepening political and economic relations between HNs and FNs” (Stoicescu and Järvenpää, 2019, p. 16). Therefore, three essential elements in the study are analysed: engagement in international operations, activities in bilateral military cooperation, and economic interrelations.

3B involvement in international operations

Estonia supports security initiatives of other NATO/EU member states and participates in the French-led Operation Barkhane and the Takuba Task Force in the Sahel region. Furthermore, Estonia joined the European Intervention Initiative (EII) (Hurt and Jermalavičius, 2021, p. 12). Estonian forces are deployed on the US-led operation “Inherent Resolve” and NATO mission in Iraq, the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), UN Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO), EU Training Mission in Mali (EUTM), UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), and European Union Naval Force Mediterranean Operation IRINI (EUNAVFOR MED IRINI) (Estonian Defence Forces [MIL], 2023).

Latvia participates in six military operations with 141 soldiers: the NATO Mission and “Inherent Resolve” in Iraq, the NATO Mission in Kosovo (KFOR), EUNAVFOR MED IRINI, EUTM, and MINUSMA (Ministry of Defence, Republic of Latvia [MOD], 2023).

Lithuania has more than 300 troops deployed on ten international operations: the NATO Mission and “Inherent Resolve” in Iraq, the US-led operation in the Straits of Hormuz, KFOR, EUTM, MINUSMA, EUNAVFOR MED IRINI, and EU’s military operations in Atalanta. The most significant change in deployment geography was the plan to join the French-led Takuba mission in Mali and the EU’s training mission in Mozambique (Lietuvos Respublikos Seimas [LRS], 2021).

The 3B are involved in international operations, regardless of emerging threats to their sovereignty. Lithuania remains the most significant contributor from 3B regarding personnel deployed overseas. 3B nations deploy troops to the same operations, although with some differences. Firstly, the 3B remains involved in NATO’s operation in Iraq, but Lithuania and Latvia additionally send troops to KFOR. Secondly, 3B sent troops to the US-led “Inherent Resolve” in Iraq, and Lithuania deployed troops to support another US initiative—the ongoing operation in the Straits of Hormuz. Thirdly, in support of the UN, the 3B contribute to MINUSMA whereas Estonia is deploying its troops also to the UNIFIL and UNTSO initiatives. Fourthly, the 3B participate actively in EU operations, such as the EUTM Mali and EUNAVFOR MED IRINI. In addition, Lithuania participates in the Atalanta and Mozambique missions. Fifthly, Estonia and Lithuania are involved in Operation Barkhane. Lastly, Lithuania was involved in a military training operation in Ukraine.

There is no supporting evidence that the 3B support their eFP FN whilst deploying additional troops to the international operations, as most international operations where FNs and HNs participate fall under a NATO, UN, or EU framework. Locally and mission-wise, countries can choose where to deploy their troops (e.g. Estonian soldiers were serving within the UK-led Kabul Security Force; Ministry of Defence, Republic of Estonia [MFA], 2020), which is a tactical choice with a tangible political dividend.

Bilateral military arrangements

Estonia and the UK

Estonian and the UK bilateral cooperation has always been good, as “communication takes place on the level of ministries and offices as well as on a higher political level.” The UK and Estonian diplomatic relations were re-established on 5 September 1991 (MFA, 2023). The more detailed defence and security cooperation agreement was signed in December 2013. This was testament to “the UK’s close ties and commitment to engage in joint activities with Estonia” (Holtby, 2014).

The bilateral military cooperation started in the 1990s when instructors from the United Kingdom helped build the defence forces training system (Kaitseministeerium [Estonian Ministry of Defence], 2017). In addition, the UK army instructors have trained non-commissioned officers (NCOs) in Estonia, and British lecturers have taught at the Baltic Defence College. Estonia acquired modern Sandown class minesweepers from the United Kingdom (Kaitseministeerium [Estonian Ministry of Defence], 2015a). Once accepted into NATO, Estonia sent an infantry company to NATO’s operation in Afghanistan as part of the UK’s brigade (Kaitseministeerium [Estonian Ministry of Defence], 2017). Estonian helicopter pilots served in Afghanistan within the deployed UK units (Kaitseministeerium [Estonian Ministry of Defence], 2015a).

Both prime ministers noted common interests in military cooperation fields, including “[the] UK military commitment within NATO’s eFP and through the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF),” “military exercises and BAP, hosting the Defence Innovator Accelerator for the North Atlantic European HQ, providing Ukraine with military aid,” and “promotion of cyber research and development.” Furthermore, other cooperation areas like “increased trade and investment” and “tech partnership” were identified (Valitsus, 2022).

Other activities, such as the participation of British soldiers in the Independence Day parade (Holtby, 2014), contribution of personnel to the NFIU and NATO’s Cooperative Cyber Defence CoE (Kaitseministeerium [Estonian Ministry of Defence], 2018c), conducting of exercises “the Baltic Protector,” “Tractable,” (Kaitseministeerium [Estonian Ministry of Defence], 2019), and “Kevadtorm/Siil,” and continuous sending of instructors to Estonia and inviting Estonian troops to attend British military academies (Kaitseministeerium [Estonian Ministry of Defence], 2015b) contribute to the closer ties in the military domain. Furthermore, the United Kingdom and Estonia are collaborating on Baltic mine-clearing operations (Holtby, 2014), and the eFP has agreed to test innovative Estonian companies’ solutions (Kaitseministeerium [Estonian Ministry of Defence], 2022).

Estonia and the United Kingdom cooperate in the Northern Group (MFA, 2021), and both parties were interested in the creation of the NATO Multinational Division Headquarters North (MND-N) and in deepening cyber defence cooperation (Kaitseministeerium [Estonian Ministry of Defence], 2018b). Cooperation occurs within JEF and EII, where Latvia and Lithuania are not involved (Kaitseministeerium [Estonian Ministry of Defence], 2018a).

Interestingly, the United Kingdom’s participation as FN in Estonia was challenged as the United Kingdom left the EU prior to the 2016 Warsaw Summit, “raising doubts about British engagement in European security affairs.” Similarly, the United Kingdom’s 2021 integrated review highlighted its potential tilt to the Indo-Pacific and cuts in the British army and to British strategic lift capabilities as plans were made to bolster the Royal Navy. This caused concern in Estonia about whether “the UK will be more capable of reinforcing them or, if necessary, engaging in a high-intensity conventional conflict to defeat Russian occupying forces” (Lanoszka and Hunzeker, 2023, p. 93).

Latvia and Canada

Latvia and Canada have developed bilateral relations over the years. Canada was the first G7 country to recognise Latvia’s independence in 1991 and the first NATO country to ratify Latvia’s membership in NATO (MOD, 2022).

Besides Canada leading the eFP, there are other venues where both countries cooperate (MOD, 2022). It is important to note that Canada’s eFP mission in Latvia is part of Operation Reassurance (Government of Canada, 2016a) which includes the assignment of a Halifax-class frigate to NATO’s Maritime Command and the allocation of an air task force (Government of Canada, 2016b).

Both countries cooperate in cyber security (MOD, 2022), and participate in the Latvian-led exercise “Silver Arrow” (Government of Canada, 2017b). Sailors from both countries participate in the exercises “Open Spirit,” which aims to clear naval mines and dispose of the same (Government of Canada, 2017a). Furthermore, Canada joined the NATO Strategic Communications CoE (Government of Canada, 2017c) and assigned officers to MND-N, which controls eFPs in Latvia and Estonia (Government of Canada, 2022).

Canadians invested in infrastructure, including a new headquarters building for Canadian Task Force Latvia (Government of Canada, 2021). Canadian Task Force Latvia ensures messaging continuity and implements a “whole-of-government approach so that political, economic, and military actions and messages are thematically consistent and well-integrated” (Macdonald-Laurier Institute [MLI], 2021). Cooperation also takes different forms, such as participation in national song and dance festivals (Government of Canada, 2018).

Besides military cooperation, Canada is keen to develop business relations in the region; as a result, the “Twelve Cities Programme” was launched. As proof of bilateral interest in economic cooperation, the procurement of nearly sixty aeroplanes by the Latvian state-owned Air Baltic from Canada’s Bombardier Inc. was conducted (Stoicescu and Järvenpää, 2019, p. 16).

Canada is slowly building up its military might and increasing its ability to sustain high-intensity combat operations. Commentators agree that awareness of Canada’s role as FN has to be raised among its public to influence national “willingness and resolve [as] questions may be asked of Ottawa’s commitment to the deployment in case of major aggression.” Note that “Canada had been the most hesitant” from FNs to reinforce eFPs with more troops in 2022 (Lanoszka and Hunzeker, 2023, p. 95).

Lithuania and Germany

Official cooperation started with the Agreement on Cooperation in the Field of Defence, signed in 1994 and renewed in 2010 (Ministry of National Defence of the Republic of Lithuania [KAM], 2023). The latest agreements concerning the temporary locating of both countries troops within each other’s borders and mutual protection of classified information were signed in 2020 (KAM, 2020c).

Besides leading an eFP, Germany is actively participating in BAP and, since 2012, has carried out five deployments to Siauliai (Lithuania) and six to Amari (Estonia) (KAM, 2023). Germany’s resolve to protect Lithuania is also visible in the maritime domain; the regular visits of German submarines to Lithuania’s seaport emphasises this (KAM, 2019b). To further increase training opportunities and cooperation, a mechanised infantry brigade of the Lithuanian Armed Forces was affiliated with a German Bundeswehr Division in 2018 (KAM, 2020b).

Germany is one of the leading arms importers in Lithuania, supplying the Lithuanian Armed Forces with the majority of manoeuvre and firepower capabilities (KAM, 2022a). Some see this a venue for potential bilateral cooperation—collaborating through arms manufacturing is gradually developing as the relationships mature (KAM, 2022c). The intent to open a Rheinmetall ammunition factory in Lithuania signifies a closer economic–military partnership (LRT, 2024).

Three infrastructure projects in Lithuania devoted to eFP are fully funded by the Federal Ministry of Defence of Germany (KAM, 2022b). The estimated project value was €100 million, which were invested up to 2023, and another €150 million subsequently (KAM, 2021b). In addition, Germany financed temporary infrastructure for the eFP and acquired target lifters in the training area while spending over €62.3 million in 2017–2018 and roughly €87.4 million in 2019–2021 (KAM, 2021c).

Germany is regarded as Lithuania’s main partner in international operations, such as MINUSMA and EUNAVFOR MED IRINI (KAM, 2021a). Furthermore, Germany contributes to NFIU and NATO’s energy security CoE (KAM, 2021c). The German Deployable Control and Reporting Centre was also deployed in Lithuania to support situational awareness of 3B airspace (KAM, 2020a).

German troops built excellent relations with local communities, schools, and municipal administrations and actively participated in various social and cultural projects (KAM, 2019a).

Germany is over-calibrating its defence policy with its declared Zeitenwende decision to boost defence spending (€100 billion upgrade of Bundeswehr Division), including the commitment to achieve 2% of GDP defence expenditure (Mälksoo, 2024, p. 542). Germany is the only EU country serving as an FN in 3B. According to plans, Germany is committed to sustaining a three-brigade division capable of high-intensity operations by 2027 and permanently deploying one brigade in Lithuania (Lanoszka and Hunzeker, 2023, p. 94). The initial decision to have only the German brigade’s command staff permanently stationed in Rukla and the rest of the force remaining in Germany was reversed in favour of a Lithuanian request for a permanent deployment of an entire German brigade (Matlé, 2023, p. 2).

Bilateral economic relationships

Once FNs bring their military assets into HNs to deter Russian aggression and demonstrate NATO’s resolve, international and national investors are likely to regard the economic situation within the 3B as more secure. Foreign direct investment (FDI) and trade balance could indicate economic interrelations among states and perceived security in the 3B. For that reason, two sets of data are provided, where the first portrays FDI by FNs and participant countries in eFPs (Table 5), and the second looks into the trade balance between the respective HN and FN (Table 6).

Table 5

FDI figures for the 2014–2023 period (Bank of Latvia, 2024; Eesti Pank, 2024; Lietuvos Bankas [LB], 2024).

Table 6

Overall trade balance for the 2014–2023 period (Eurostat, 2024).

Investments into HN economies from the United Kingdom and Germany increased in correlation with the timings of the first deployment of eFP troops in early 2017. The UK’s FDI increased four times whereas German’s FDI into Lithuania increased more than five times. With Canada, the contribution remained at the same level—€13 million, as the focus for Canada is only within the military domain. When considering other contributing states, Denmark, Poland, France, and Norway are all visible with their increasing FDI figures. However, FDI from the Netherlands and Luxemburg must be carefully interpreted, as these countries have a more conducive tax regime and multiple investment treaties that ensure investor protection.

Like most other small states in the world, all 3B nations have a deficit trade balance, including in bilateral trade balance with FNs. FDI and trade balance indicate an increasing economic interrelation between the United Kingdom and Estonia, and Germany and Lithuania. Once the eFP units were deployed in the area, the FDI figures increased sharply (especially in Estonia and Lithuania), indicating long-term investors’ commitment, decreased concern for security, and the expressed political will for future cooperation.

Discussion

The 3B, faced with the threat posed by Russia, reacted collectively and requested the strengthening of NATO’s eastern flank through military means. However, the delayed decision for battalion-size unit deployment (request in 2014 and deployment in 2017) indicates small states’ lack of relative power to influence large and mid-power states (R2), in this case contradicting or not being entirely in line with the postulates of most small state theories (Table 1). Thus, 3B activities in the eFP context could be better explained with several small state theories, such as alliance theory, alliance shelter theory, and the theory of free-riding (R1).

After assessing the 3Bs’ military expenditures (>2% GDP), reforms, and plans to improve the capabilities of their armed forces, it is clear that the free-riding theory is not relevant for application, and instead could be used in assessing FN’s behaviour. Canada and Germany are still on the way to reaching the agreed-upon benchmark for defence spending (Canada spent 1.38% and Germany 1.57% of GDP in 2023).

The alliance theory could support the explanation (R1) of Canadian and Latvian cooperation activities, as they focus more on the military domain. Political and economic cooperation is restrained due to distance. The theory plays well with empirics only in some aspects, such as the importance of FN’s contribution to an HN’s ability to defend and increase security. However, Latvia, in particular, is not seeking to promote its domestic interests to the international community, nor is it hampering agreed activities as it would be if it followed the scholars’ (Bailes et al., 2016; Thorhallsson and Steinsson, 2017; Urbelis, 2015) thoughts. There is no evidence suggesting that Latvia is being restrained by Canada, as per the alliance theory; even more, Canada incurs the financial and political cost in short- and mid-term in return for diplomatic recognition and wider political acceptance (Leuprecht and Sokolsky, 2017, p. 22).

The UK–Estonia and Germany–Lithuania nexus, with more established venues of cooperation, can be explained using the alliance shelter theory (R1). The current situation reaffirms Vaicekauskaitė’s (2017, p. 8) statement that mutually beneficial cooperation “has to be based on other factors and not only on power calculations” as HNs and FNs seek interests in various venues. The nexus is “neither based solely on subordination or annexation nor equality or autonomy,” as both HNs cooperate with other states and work freely in an international framework. Nevertheless, the alliance shelter theory can only partially be adapted to this situation as, according to Bailes et al. (2016, p. 17), small states have to bear a high cost and benefit disproportionately, compared to large states. The higher cost that small states incurred in the eFP construct is an increase in defence spending and a more proactive leaning towards mid-powers. The eFP framework did not force an increase in defence spending as an obvious Russian threat influenced it. All NATO states, including FNs, increased spending, and rather FNs invested meaningfully in HNs’ infrastructure. Furthermore, small states gained more security in military terms, although they partly benefited in the economic domain. The FNs’ ability to shape political domain is questionable, as small states operate within the international framework. Furthermore, as mid-powers compete for prestige and a reputation as a “loyal ally,” they are interested in demonstrating their military, political, and economic power whilst dealing with various voluntary tasks within NATO.

The alliance and alliance shelter theories explore the relationship of small states with major powers, although they do not focus on explaining cooperation with mid-powers. The relationship between small- and mid-power states is entirely different from the one between small and major powers, which is evident in this study. The ability of mid-power states to support small states with military means is unquestionable because they have sufficient resources to do so. However, their political, economic, and social influence can be questioned. In NATO, it is rather challenging to influence small states, as they can influence decisions if they act smartly (R2).

Conclusions

As a response to the Russian aggression in Ukraine, the establishment of NATO’s eFP in 3B (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), where medium powers, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Germany, took role as FN and 3B act as HN, formed a new normal in NATO. The eFP framework facilitated increased interaction amongst HNs and FNs in the military, political, economic and social domains.

Although restricted in the scope (involvement in international operations, bilateral military cooperation, and economic relationships) and time period analysed (2014–2023), the study examined the nexus between HN and FN in the eFP framework in 3B from a small state perspective while referring to IR theories that discuss small state behaviour.

The findings suggest that IR theories can explain the behaviour of the 3B (R1) in the eFP framework. Alliance, alliance shelter, and free-riding theories are most appropriate for analyses of 3B in the eFP context, although only partially. Canadian (FN)–Latvian (HN) cooperation activities can be explained using the alliance theory whereas cooperation between UK and Estonia, and Germany and Lithuania can be better defined by the alliance shelter theory. Meanwhile, the free-riding theory was found to be irrelevant in this case, as 3Bs’ defence budgets remained above 2% of GDP. Interestingly, one particular IR theory could not explain 3B activities, although 3Bs are being treated as a homogenous group and are located in the same geographical location and surrounded by a similar security environment.

Analysis of the case of eFPs in 3B indicates that small states can balance medium powers (R2) in a limited scope through their forward-leading behaviour in bilateral cooperation (while acting in multiple domains, including military) and clever arrangements in NATO. Mid-powers in the eFP construct are rather influenced by their motivation, such as seeking international prestige, being identified as a “more loyal ally,” and being able to demonstrate military, political, and economic power. As a result, this motivation now plays into the hands of 3B.