Introduction

Operational fires represent one of the most important operational functions. The success of operational fires primarily depends on synchronisation and synergy with other operational functions, especially intelligence and logistics.

The ability of rapid projection of combat power, at the decisive place and time, is the key to success of any military action.

Operational fires are used for (Vego 2007):

Isolating or shaping the battlefield / battlespace,

Facilitating operational maneuver of friendly land forces,

Preventing the enemy’s operational maneuver,

Destruction, holding up or disrupting of the enemy’s reserve forces,

Destruction or neutralisation of the enemy’s main forces,

Disrupting or cutting of the enemy’s logistical support,

Deceiving the enemy about the real main course of attack,

Diminishing of the enemy’s morale,

Protection of one’s area of operations,

Protection and development of newly taken naval bases and airports,

Preventing the enemy’s retreat or withdrawal.

Operational fires are most commonly used to isolate or shape the battlefeild / battlespace by preventing the arrival or slowing down the movement of enemy land, air or naval forces.

The aim of this work is to show and analyse operational fires in Operation Leyte, the largest naval and air operation of World War II.

Operation Leyte

Approaching the Philippines

The main Allied, i.e. American strategy, in the Pacific in 1943 and 1944 was “island hopping” (Pomorska enciklopedija 1978). It consisted of reaching the Japanese rear by bypassing most of the island strongholds on that line of advance. The Americans would simply land in the rear, build their naval and air bases and the Japanese bases left behind would be subjected to aerial and naval bombardment, i.e. a blockade with the aim of destruction. Such a strategy caused an unstoppable Allied advancement in the Southwest, i.e. the Central Pacific. Of course, besides the strategy itself, the advancement was also possible thanks to the huge US material and industrial power since it was located far away from the battlefields and the ravages of war, and it supplied the military with modern weapons systems in great numbers. The balance of power can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1

US naval power (adapted from Mamula 1975)

| SHIP TYPE | YEAR | |

|---|---|---|

| 1941 | 1944 | |

| Aircraft carriers (all types) | 7 | 125 |

| Battleships | 16 | 23 |

| Cruisers | 36 | 67 |

| Destroyers and escort ships | 180 | 879 |

| Submarine hunters | - | up to 900 |

| Submarines | 112 | 351 |

| Landing ships | - | 75,00 |

American Action Plan

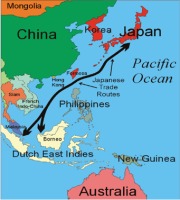

In the summer of 1944, the Americans advanced toward the Philippines and Japan from two directions. General MacArthur controlled New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Rabaul, an important base, while Admiral Nimitz occupied the Mariana Islands. These conquests created conditions for an attack on Asia, i.e. for the final destruction of Japanese military might. American commanders had different views on how this should be done; Admiral Nimitz wanted to attack Japan directly, while General MacArthur (partly due to his hurt vanity) wanted to conquer the Philippines first. In the end, President F. Roosevelt chose MacArthur’s plan (Pomorska enciklopedija 1978).

A modified plan included landing on the Morotai and Peleliu Islands in September; Yap, Ulithi and Talaud Islands in October; Mindanao in November and, in the end, on the Philippine island of Leyte in December.

For making this operation possible, the following forces were chosen: the SW Pacific Forces (7th Fleet and 6th Army) under the command of General MacArthur, and the 3rd Fleet (Central Pacific Forces) under the command of Admiral Nimitz. The forces had 35 aircraft carriers, 12 battleships, 25 cruisers, 144 destroyers, 39 torpedo boats, 29 submarines, and 1,350 aircraft aboard the carriers and 182 at the airbases, including a large number of transport and auxiliary ships (Kitanović 1985). The planned success of the operation was to be achieved by the use of air power.

Japanese Action Plan

After the loss of the Mariana Islands and New Guinea in the summer of 1944, the Japanese HQ had adjusted its last defence strategy. The natural brunt of defence lay at the islands of Japan (metropolis), although the Philippines, Formosa (Taiwan) and Ryukyu were vital for the security of Japan. The inland waterway, which was still protected, could have still been used by the shrunken Japanese tanker fleet, carrying oil from the Dutch East Indies (DEI), Indonesia into the metropolis. The loss of the Philippines would cause the break of vital communications, which would lead to a disaster because the forces in the north would be left without fuel and those in the south would be left without weapons, ammunition and equipment.

In order to avoid the worst scenario, on July 21, 1944 Japan developed a plan called Sho-Go (Operation Victory), which was to be achieved through four phases: Sho 1 – the defence of the Philippines, Sho 2 – the defence of Formosa, Sho 3 – the defence of central Japan, and Sho 4 – the defence of northern Japan (Pomorska enciklopedija 1978). The Sho-Go plan predicted a concentration of overall naval and air forces against the next American amphibious assault in which the land- based air forces should strike first. The Combined Fleet was supposed to play the main role. At the right moment, it should have broken through to the landing spot and destroyed the American landing forces.

The Japanese engaged their whole fleet, Strike Group A, under the command of Admiral Kurito, Strike Group C under the command of Admiral Nishimura, the Second Strike Detachment of Admiral Shima and the main forces of Admiral Ozawa. In this operation, all admirals, except Admiral Ozawa, were not up to the task or they were already aware of their doom (Prikril 1985).

Had the Japanese been successful in achieving their goals, those naval and air strikes would have been called operational fires; however, they did not succeed.

American Operational Fires

The American forces achieved great success with effective planning of air strikes (operational fires), even before the landing itself, which occurred on October 17, 1944, by isolating the Philippines, especially Leyte Gulf.

The Leyte Gulf isolation began 7 days prior to occupation of the Philippines. The four aircraft carrier groups of the TF 38 of the US 3rd Fleet attacked the Japanese forces along the coast of Indochina several times, from Saigon in the South to Quinho in the North, including the Japanese navy assets and merchant ships along the coast and in Cam Ranh Bay between September 9-11. The aircraft carriers were persistent in their attacks on harbours and ships in Hong Kong, Canton, Hainan Island and Taiwan from September 15-17. From September 21- 22, the TF 38 aircraft attacked the Japanese air bases in Taiwan, the Pescadores, Sakishima, Gunto and Ryukyu Islands. Additionally, the US Air Force attacked the Japanese ships at three harbours in Taiwan. Before landing in Leyte Gulf, the Allies had additionally strengthened their activities related to the Philippines isolation. Heavy and medium bombers were used to the maximum extent to isolate the central Philippines, especially Leyte Gulf. In fact, the Allied air forces blocked all air and naval approaches to the Philippines. The US 3rd Fleet was tasked with blocking the arrival of Japanese air reinforcements from the Japanese islands, Ryukyu, Taiwan and the Chinese mainland. On October 10, the TF-38 attacked Okinawa Island and Ryukyu. From October 12-14 an aircraft carrier group attacked Taiwan with the aim of preventing Japan using the island as an air base for reinforcement of the Philippines. The main targets in Taiwan were air bases and ships. On the second day, the air power was used again against the Japanese air bases in Taiwan, together with 109 B-29 bombers of the 20th Army Bomber HQ in China, with its target being the Takao area. The 14th United States Army Air Force (USAAF) bombarded the Japanese air force installations at Kunming (1,600 km away), including Hong Kong, Hainan and the Gulf of Tonkin. Furthermore, on October 16, 50 B-24 and B-25 of the 14th USAAF attacked the ships and naval installations in the Hong Kong area. On October 17, the first air wave rocketed, bombarded and air strafed three air bases on Ryukyu Island, merchant navy ships and naval installations.

The Far Eastern Air Force (FEAF) based on Morotai, Biak and New Guinea Islands, helped in the preparation of Operation Leyte by attacking the Japanese air bases on Mindanao Island. Furthermore, numerous attacks were carried out almost on a daily basis against ports and oil installations in the DEI. These were aimed against the use of Japanese forces in the DEI (that were supposed to act in the event of an Allied attack after the Leyte Gulf landing) and also to destroy the Japanese oil industry in the area. The North Pacific forces attacked the Japanese forces on the Kuril Islands. At the same time, bombers of the North Solomon Air HQ, based on the St. Matthias Islands, isolated the Japanese garrisons on Truk and other Carolina islands. Around 1,000 fighter and medium bomber sorties were carried out in October in order to achieve these goals. The Far Eastern and the Central Pacific Air Forces attacked the Japanese air bases on Marshall Islands. From October 8-10, the USAAF based on these islands attacked the Volcano and Bonin Islands, which were under Japanese control. The Northern Pacific Forces only attacked the Kuril Islands. The SE Asia HQ provided support to Operation Leyte by strengthening its land and air operations in Burma, which started on October 5. From October 15-25, Bangkok and Rangun were attacked by air. Joint efforts by the TF-38, escort carriers of the 7th Fleet and land-based USAAF enabled absolute air superiority over the Philippines during the Leyte Gulf landings (Morison 1958).

By isolating the Philippines, especially Leyte Gulf, conditions were created for the Allied landing, which started on October 17, by landing on Suluan Island, followed by landings on the Dinagat and Homonhoni Islands and finally on Leyte Island on October 20.

Naval battles between the US submarines and the forces of Admiral Kurito started on October 23. Operation Leyte lasted from October 23-26 and consisted of 4 major battles: October 24 – the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea; October 24-25 – the Battle of Surigao Strait; October 25 – the combined Battle at Cape Engano, and October 25 – the Battle of Samar.

Japanese Operational Fires

The Japanese HQ considered the battle of Philippines to be crucial for winning the war, so it developed the Sho-Go plan (victory plan), in which phase one (Sho 1) represents the defence of the Philippines. New tactics were developed along with the new plan. In order to avoid naval artillery fire, the troops were ordered not to expect the landing force on the shore, but to withdraw to the inner of the islands, fortify themselves heavily and not to make useless charges with flags and sabers ahead of them (Kitanović 1985). In this extremely important operation, every Japanese soldier was badly needed and any futile act of heroism was prevented.

According to the Japanese, operational fires should have been achieved by a synergy of naval and air forces, but apparently they were wrong because the American ones were superior and outnumbered theirs in both quality and quantity.

After the catastrophic defeat in naval and air operation in the Philippine Sea and round-the-clock bombardment, the Japanese fleet was left with no experienced and well-trained pilots and could no longer compete with the American fleet. The Japanese tried to neutralise American war material superiority by sacrificing their own pilots.

Kamikaze

The kamikazes (Japanese tokko – divine wind) were Japanese suicide pilots whose only goal was to crash their planes into the target location. The Japanese Air Force started to use them in October 1944. The first Allied ship hit by a kamikaze was an Australian heavy cruiser HMAS Australia (October 21, 1944). By the end of the war, according to Japanese sources, the Japanese Naval Air Service sacrificed 2,525 pilots and the Air Forces lost 1,387 pilots. According to American sources, around 2,800 kamikazes sunk 34 ships, damaged 368, killed 4,900 and injured over 4,800 sailors (Kamikaze in wikipedia).

Apart from the kamikazes, Japan also used suicide divers (Fukuryu), motor boats filled with explosive and suicide sailors (Shinyo and Maru-ni), human anti-tank mines (Nikaku), manned torpedoes (Kaiten) and midget-class suicide submarines (Kairyu).

In naval and air operation Leyte, the Japanese used the kamikazes with the hope of winning and turning the tide of war; however, they failed because of successful American AAD and constant aerial superiority, so their successes can hardly be called tactical, let alone operational fires.

Conclusions

The goal of the Philippines military campaign was to conquer the Philippines and to cut Japan’s supply routes. That would prevent Japan from supplying itself with raw materials needed for its war industry and which were found in occupied areas. Because of this, Japan, as an island country, based its military might on naval and air forces that enabled control of those areas.

The Allied advancement towards the Philippines put Japan in a very difficult position because its only supply route was now under attack. Because of this, Japan prepared for a decisive battle in which it wanted to maximise the power of naval and land air forces and use it to destroy any landing attempt, followed by the destruction of enemy naval forces. The plan was doubtful since the American might in the Pacific was obvious.

Naval and air operation Leyte was a heavy defeat of the Japanese forces. It wasn’t a decisive battle of the war, but it was decisive for the Pacific theatre of operations.

The Japanese fleet ceased to exist as a serious combat factor and could no longer wage a battle as serious as Operation Leyte (Vojna enciklopedija 1973). The basic causes of the Japanese defeat certainly lie in the overwhelming power of the American fleet, especially its air force.

The basic characteristics of World War II, especially the Pacific theatre, can be seen in the fact that large battleships lost their dominance in battle waging and their role was taken over by aircraft carriers that became the main strike force.

The same applies to Operation Leyte. Aircraft carriers represented the main strike groups (e.g. the TF 38). Th is operation has shown that victory may be achieved with good synchronisation and synergy of all operational functions, especially operational fires. The only objection is related to the C2 (Command and Control) operational function because of command dualism (MacArthur - Nimitz). This dualism almost cost the American side their victory.

From all the above mentioned, it can be concluded that the sum of overall Allied air strikes (from both aircraft carriers and land air bases) against the Japanese forces, from Indonesia to Japan, especially the ones on the Philippines (Leyte Gulf) are the sum of tactical fires. However, viewed from the point of the final operational goal, i.e. the conquest of the Philippines, it can be said that all those air strikes used to isolate the Philippines and inflict losses upon the Japanese forces were operational fires.