Introduction

Since the accession to NATO of the Baltic states, Poland and other countries on NATO’s eastern flank, the United States (U.S.) has taken the central role in the security in the region. On the other hand, a resurgent Russia, flexing its military and diplomatic muscles in Eastern Europe since 2014, has been a significant security issue for countries in Central-Eastern Europe. As U.S. foreign policy towards Russia influences the security dynamic in this region, it should be studied closely. For example, at both the 2014 NATO Wales Summit and the 2016 Warsaw Summit, the U.S. specifically addressed the security concerns of NATO’s eastern flank countries which were caused by Russian aggression in Ukraine. Since then, the security of this region has played a key role in U.S. Operation Atlantic Resolve of the European Deterrence Initiative (formerly known as the European Reassurance Initiative), which aims to augment the U.S. air, ground and naval presence in order to bolster U.S. capabilities in the region and to demonstrate solidarity with countries on NATO’s eastern flank. To put these recent events in a wider context, this paper uses the grand strategy classification framework for answering the research question: how did the U.S. grand strategy towards Russia change 2001 to 2017?

U.S. grand strategies, the ideas that guide U.S. foreign policy, are among the analytical concepts for classification and analysis of U.S. actions in the international arena and towards Russia as well. Grand strategies are comprehensive, long-term plans used to achieve preferred U.S. foreign policy goals. Robert Art, one of the most influential contemporary scholars of these strategies, offers the most concise, yet comprehensive definition: grand strategy is “a set of foreign policy goals to pursue… that will do the best for the United States” (Art 2003, p. 1). A more elaborate definition is the one put forward by Christopher Layne: “In choosing a grand strategy, a state will define its interests and objectives, identify threats to its interests and objectives, and decide in response on the most appropriate political, military, and economic strategies to protect those interests” (Layne 1997, p. 88). These are sets of ideas, “the intellectual architecture,” “the logic that guides leaders” (Brands 2014, p. 3), “broad set(s) of principles, beliefs, or ideas that govern the decisions and actions of a nation’s policymakers” (Martel 2013). To sum up, the grand strategies of the U.S. and any other state can be defined as a set of ideas about how a state can better achieve preferred ends with available means (Kreps 2009, p. 633). Contemporary U.S. grand strategies – primacy, liberal internationalism and offshore balancing – are sets of ideas that describe what U.S. domestic and foreign policy should look like and describe the means and ends of U.S. involvement in the international system of states. In-depth comprehension of the grand strategy of the U.S. has chosen to use alternative strategies that allow us to understand the reasons why the U.S. is conducting specific foreign and domestic policies and to predict the future actions of the U.S. Grand strategies also offer a framework that allows for the systematisation, classification and analysis of U.S. actions in the international arena.

This article, firstly, gives an overview of the grand strategy classification framework used to code speeches about U.S. foreign policy towards Russia. It describes the underlying assumptions and elements behind the three most relevant grand strategies in U.S. foreign policy and in U.S. foreign policy, particularly towards Russia. This classification framework contains a detailed, unified coding system, a set of specific criteria for how to attribute different ideas about foreign policy to one or another grand strategy element. This classification was used to code speeches about U.S. foreign policy towards Russia to evaluate the role that different U.S. grand strategies and specific elements – leadership, values, cooperation, and power – have played in U.S. policy towards Russia. After the coding process, statements from speeches can be attributed to a specific grand strategy element and, thus, classified as belonging to one or another grand strategy. Even more, each element in all documents and speeches can be depicted as a percentage value to show how much emphasis the specific document or speech puts on the specific element of grand strategy. This classification allows for the clear identification of various stages in U.S foreign policy towards Russia, which are described in the second part of this article.

The time frame from 2001 to 2017 was chosen because it allows a comparison of two different U.S. administrations and allows the changes in U.S. foreign policy towards Russia after 2014 to be put into context. Speeches and statements by U.S. presidents and vice-presidents were chosen as the units of analysis according to the relevance sampling methodology (Krippendorff 2004, pp. 118-119): they are the most significant sources compared to others and they offer the most comprehensive outline of U.S. foreign policy. The President plays the central role in U.S. foreign policy decision making. U.S. government institutions, policy makers and people working on implementing U.S. foreign policy take guidance from the statements of the U.S. president. Speeches with at least five references to Russia were selected from the White House archive of the George Bush presidency (https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov ) and the Barack Obama presidency (https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov ). These sources were used because the publication of these speeches in the official White House home page indicates their significance for the respective presidential administration. Furthermore, these speeches offer the most comprehensive publicly available outline of official U.S. foreign policy towards Russia. This source therefor meets both criteria of the relevance sampling.

Altogether, 36 units of analysis were used in the coding process. To analyse grand strategies towards Russia during Bush’s presidency, 12 speeches and 4 short statements (used as a single unit of analysis) on the Russia-Georgia War during August 2008 in the speeches by George Bush were included in coding and analysis. To analyse grand strategies towards Russia during Obama’s presidency, 17 speeches and 4 short statements during Russia’s aggression in Ukraine (used as a single unit of analysis) by Barack Obama and 5 speeches by Vice President Joe Biden, being 23 units of analysis in total, were used. Speeches by Vice President Joe Biden were included in the analysis because he played a prominent role in U.S. foreign policy towards Russia.

Grand Strategy Classification Framework

Since the late 1980s, a multitude of scholars, experts and pundits have offered their insight into what the U.S. grand strategy for the post-Cold War world should be. The grand strategy classification used in this article builds on and expands the classification offered by Barry R. Posen and Andrew L. Ross (1996, pp. 22-30). There are three distinctive grand strategies (see Table 1) relevant for U.S. foreign policy towards Russia: primacy, liberal internationalism and offshore balancing. This classification framework operationalises each grand strategy as a sum of four different elements. Firstly, what role should the U.S. play in the world? Secondly, what role do values and ideals, such as democracy and human rights, play in U.S. foreign policy? Thirdly, what role should cooperation take in U.S. interaction with other states and international organisations? Fourthly, what type of power should the U.S. emphasise in the international arena? According to Sartori’s description of minimal definitions, it is necessary to make abstractions to be able to define concepts and any definition should include only the minimum necessary characteristics to give a complete description of any concept (1970, p. 65). The sum of these four elements – leadership, values, cooperation, and power – is the minimal number of characteristics that allow for the definition of each grand strategy.

Table 1

The U.S. grand strategy classification framework (Posen and Ross 1996, pp. 22-30)

The first element on which there are major differences between grand strategies is about the global role the U.S. should take. Most authors differentiate between active, dominant grand strategies supporting U.S. leadership and grand strategies that prefer the status quo or even retrenchment and withdrawal from the international arena. Looking at the classification framework, primacy and liberal internationalist grand strategies support U.S. leadership: proactive U.S. foreign policy. Primacists argue that the U.S. should take an active leadership role in the global arena because U.S. leadership has historically provided peace and stability in the international system, thus the U.S. should continue this successful policy of active engagement (Kagan 2012, pp. 5-6). Liberal internationalists argue that U.S. leadership is necessary to ensure collective action and to prevent great power competition (Haass 2005, pp. 23-24). Another possibility is for U.S. foreign policy to be less active, to decrease U.S. engagements in the world, and offer less U.S. leadership and involvement. Offshore balancing grand strategy supports balancing and burden-sharing with other states. For example, Mearsheimer argues that the U.S. is wasting its resources by getting actively involved in solving many problems across the world and thus promotes the free-riding of U.S. allies and other states. The U.S. should only get actively involved in the international system as a balancer of last resort when international balances of power break down (Mearsheimer 2011, pp. 18, 31-34). Support for more active U.S. leadership or a less active role of balancer is the first indicator by which grand strategy classification can start.

A similar dichotomy exists about the second element of this classification. Different grand strategies assign a varying level to the extent idealist values like democracy, human rights, rule of law, individual freedoms, responsibility to protect should play in U.S. foreign policy. Liberal internationalist and primacist grand strategies share their origins in liberal international relations theory and support idealist foreign policy. Both strategies agree with the democratic peace theory: democracy, human rights, and other values are essential for a peaceful and stable international system because democracies do not fight aggressive wars against each other. A more democratic world would be in U.S. interests, thus the U.S. should use its current unipolar preponderance to promote and defend democracy, human rights, rule of law, prevent genocide and defend other liberal values (Haass 2005, p. 20, Kagan 2012, p. 4, Martel 2013). Offshore balancing grand strategy, contrary to the previous two, supports the idea that pragmatic foreign policy will be more successful. The U.S. should be able to pragmatically cooperate with non-democratic states and should not promote democracy internationally. Democracies can also oppose and hinder U.S. foreign policies (Mearsheimer 2011, pp. 18-19). The U.S. should not treat authoritarian states differently, because their support is necessary to address various international problems. If idealist values are at the forefront of U.S. foreign policy, cooperation with authoritarian governments would become impossible. The U.S. should look at whether these states are ready to cooperate with the U.S. or not (Mearsheimer 2005). The second indicator, which makes grand strategies different, is support for a more idealistic or more pragmatic U.S. foreign policy.

Primacy and liberal internationalist grand strategies support active U.S. leadership and the promotion of idealist values, but they differ on the means for providing it: they differ in the varying level of support for cooperation with other states as well as the level of support for the use of military power in foreign policy. Primacists emphasise unilateral leadership and the role of military power, while liberal internationalists, multilateralism and the role of non-military and soft power. The first grand strategy used by this classification is primacy. This grand strategy has various names; however, “primacy” is used to describe this grand strategy, because it is widely used, it is a more descriptive term and it captures the essence of a grand strategy that supports active, dominating, unilateral U.S. foreign policy (Kagan 2012, p. 59), with the emphasis on active use of military might to solve and even preempt international threats and problems from materialising. To do this, the U.S. should act alone if other countries and international organisations are not willing to act (Posen and Ross 1996, pp. 32-36, Mearsheimer 2011, pp. 18-19). Unilateralism and emphasis on military power characterises primacy and should be continued because they have created the current, relatively stable international system after the end of the Second World War.

The second strategy that the classification in this thesis uses in its analytical framework is liberal internationalism. The name liberal internationalism is used to characterise this strategy, because this is the term most liberal internationalists call themselves and this is a descriptive title that captures the essence of this grand strategy, which supports a normative, liberal agenda on a global scale. The liberal internationalist grand strategy supports multilateralism because contemporary global problems cannot be solved unilaterally – by any state working alone (Haass 2005, p. 187; Mearsheimer 2011, pp. 18-19; Sestanovich 2014, pp. 335-336). It would be easier for the U.S. to advance its interests if it was working with its partners and through international organisations to build an international consensus supporting U.S. foreign policies (Haass 2005, p. 17). Overly active use of military power in foreign policy undermines U.S. soft power. Furthermore, in the complex modern world, there are many issues military power cannot help to solve in any way (Haass 2005, p. 203). Thus, liberal internationalists prefer the use of non-military tools and soft power. Posen and Ross argue that security-building measures, economic sanctions, arms control and non-proliferation are at the core of liberal internationalism. Military force can be used when necessary, but liberal internationalists do not emphasise the use of force. It is only one of the instruments in the foreign policy toolbox and should be used cooperating with allies and through international organisations when doing so (Posen and Ross 1996, pp. 22-30; Mearsheimer 2011, pp. 18-19). Multilateralism and support for non-military foreign policy tools characterises liberal internationalist strategy.

Offshore balancing grand strategy supports decreased U.S. leadership and emphasises pragmatism. Furthermore, the U.S. should not lead the world either unilaterally, or multilaterally, but instead share the burdens of global leadership with other states, maximising U.S. power at home and upkeeping regional balances of power with minimal involvement. The U.S. should save its power. Other states should play a bigger role in the international system. With decreased involvement in the international arena, the U.S. should maximise its military power for homeland defence, build U.S. infrastructure and develop society in order to inspire other states by example. In the international arena, supporters of offshore balancing argue that the U.S. should limit its use of military power as well as military deployments on foreign soil and play the role of balancer between different players in various regional balances of power (Mearsheimer 2011, p. 18; Posen and Ross 1996, pp. 17-21). This will allow the U.S. to save resources and overcome the free-riding of other states (Mearsheimer 2011, pp. 31-34). Burden sharing with other states, maximising power at home and balancing regional balances of power are elements which define offshore balancing strategy.

Building on the grand strategy classification framework, each grand strategy is operationalised as a sum of different ideas about U.S. foreign policy, the sum of four different elements that make up foreign policy: 1) the role that the U.S. should take globally; 2) the role values should play in foreign policy; 3) the role cooperation should play in foreign policy; and 4) what the key source of U.S. power is in international relations. This classification, these ideas, keywords, and concepts described were previously used in coding to identify each grand strategy element in order to reduce the vast number of concepts and summarise ideas in the speeches of U.S. presidents and vice-presidents. Reducing data to manageable representations allows the analysis of these documents and speeches using quantitative methods: counting words in sentences that support one or another grand strategy element. This classification framework makes grand strategy applicable for empirical analysis and allows for the specific measurement of support for different grand strategies in speeches.

Stages in U.S. foreign policy towards Russia 2001–2017

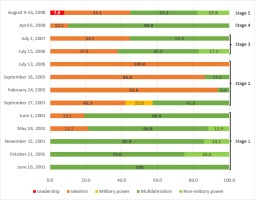

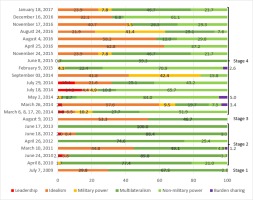

To identify and analyse changes in U.S. grand strategy towards Russia from 2001 to 2017, speeches from the White House archive were used. There were 12 speeches and four short statements on the Russia-Georgia War during August 2008 counted as a single unit of analysis with at least five references to Russia in them in the White House archive of George Bush’s presidency from January 2001 to January 2009 (Figure 1). During the presidency of Barrack Obama, the number of speeches devoted to Russia increased, initially because Obama attempted to reset relations with Russia and later because U.S. and Russia were on the opposite side in multiple conflicts. For example, in Syria and Ukraine and Russian interference in the U.S. presidential election during 2016. Thus, for analysis of Obama’s grand strategies towards Russia, 23 units of analysis, four short statements from which during Russia’s aggression in Ukraine were counted as a single unit of analysis, were used (Figure 2). These speeches were coded according to the grand strategy classification framework. Figures 1 and 2 show the results of the systematic in-depth content analysis of speeches, offering the percentage of support for each grand strategy element in each speech. Based on which grand strategy elements were emphasised more in these speeches, it was possible to identify five different stages of U.S. foreign policy towards Russia during Bush’s presidency and four stages during Obama’s presidency. Furthermore, the results of this coding process are put in context with descriptions of U.S. foreign policy towards Russia by other authors.

There were five different stages in U.S. foreign policy towards Russia from 2001 to 2009 in the speeches of President George Bush. The first stage in Bush’s foreign policy towards Russia lasted from Bush’s inauguration until mid-2003. The emphasis here was on multilateralism. For the U.S. after 9/11, cooperation with Russia was a “critical element in the global effort against terrorism” and needed for a “post-conflict settlement in Afghanistan” (The White House Office of the Press Secretary, October 21, 2001) as well as solving other global challenges. Bush emphasised elements of liberal internationalist strategy but did not talk about idealist values much. Various authors argue that after the September 11 terrorist attacks, Bush embraced the strategy of democracy promotion: support for democratic movements and ideas across the world using unilateralism and preemption (Cox, Lynch, Bouchet 2013, p. 10, 26; Martel 2015, p. 321, 323). While Bush did start to talk about democracy promotion in his National Security Strategy in 2002, only in his June 2003 speech did Bush link democracy in Russia with positive relations with the U.S. However, cooperation still was the main emphasis of this Bush speech. Emphasis on the liberal internationalist strategy towards Russia was maintained throughout Bush’s speeches; however, the role of idealist values changed over the years.

The second stage started from mid-2003 and lasted until July 13, 2006. This stage was notable for its emphasis on idealist values, particularly democracy promotion in foreign policy towards Russia. Contrary to the first stage, cooperation played a minuscule role in this stage. Bush hoped that Russia would be “a country in which democracy and freedom and rule of law thrive” (WHOPC 2003). Democratisation was a precondition for increased cooperation between the two states. Russia “will be an even stronger partner as the reforms that President Vladimir Putin has talked about are implemented – rule of law, and the ability for people to express themselves in an open way in Russia” (WHOPC 2005). This change of rhetoric coincided with deteriorating democracy in Russia as well as with various disagreements between both states, for example, about Chechnya, Iraq, and others. This analysis of Bush’s speeches also corresponds to what various authors have written about this period in U.S. relations with Russia. Goldgeier argues that Bush used a “linkage” strategy towards Russia. A foreign policy which connected democracy and the human rights situation in Russia with cooperation between the two states on other issues (Goldgeier 2009, p. 23). If Russia democratised, it would get increased cooperation from the U.S. (Mankoff 2012, p. 115). As democracy and the human rights situation in Russia deteriorated, Bush responded with an increasing use of idealist criticism of Russia, which led to a gradual deterioration in the U.S.-Russia bilateral relationship (Dayermond 2013, p. 506). Nonetheless, this did not change U.S. strategy towards Russia. Bush emphasised idealist values more but did not abandon rhetoric about cooperation. This was still a liberal internationalist approach towards Russia because primacists argue that cooperation with authoritarian states which have opposing interests to the U.S. should not take place (Kagan 2007, pp. 33, 35).

The third stage lasted from July 15, 2006 and until the beginning of 2008. This stage consisted of short, vague statements about Russia which lacked specific detail and can be described as a drift in U.S. foreign policy towards Russia. “Drift” was a term that was later used by the Obama administration to describe relations between U.S. and Russia during the second Bush administration (WHOPC, November 18, 2010). The fourth stage – Bush’s reset – was a new stage started in U.S. foreign policy towards Russia from April 2008 until the Russia-Georgia war which started on August 7, 2008. Bush offered a more specific agenda in relations with Russia compared to the previous stage and placed emphasis on multilateral cooperation, putting almost no emphasis on idealist values. For example, his April 6, 2008 speech discussed cooperation “in missile defence,” “to stop the spread of dangerous weapons,” to “meet the threat of nuclear terrorism” as well as other issues: “when you work hard, you can find areas where you can figure out how to cooperate” (WHOPC, April 6, 2008). This was a major change from the previous drift phase in Bush’s foreign policy towards Russia and offered a far more specific foreign policy towards Russia as well as a positive agenda. This stage is often missing in the analysis of Bush’s foreign policy towards Russia.

After Russian aggression in Georgia August 2008, Bush started talking about Russia in the fifth stage using idealist, multilateralist and non-military power grand strategy elements. Bush talked about idealism: “support for Georgia’s democracy.” Nonmilitary tools in foreign policy: “humanitarian assistance to the people of Georgia.” Multilateralism: “working closely with our partners in Europe and other members of the G7 to bring a resolution to this crisis” and “hope Russia’s leaders will recognise that a future of cooperation and peace will benefit all parties” (WHOPC, August 15, 2008). However, the emphasis was not on multilateral cooperation with Russia, but cooperation with U.S. allies multilaterally against Russia. Nonetheless, all this last stage was in accord with the liberal internationalist strategy and lacked primacist unilateralism and military power elements. Thus, it can be concluded that throughout these five stages, Bush used a liberal internationalist grand strategy towards Russia.

In 2009, with a new president Barack Obama in the White House and a new president Dmitry Medvedev in the Kremlin as well, the relationships between both states entered a new stage. To summarise the coding results of speeches and statements – 23 units of analysis, there were four stages in U.S. foreign policy towards Russia during Obama’s presidency (Figure 2). The first stage in Obama’s foreign policy towards Russia during 2009 can be symbolically described as extending a hand to Russia. The U.S. and Russia should pursue “a sustained effort among the American and Russian people to identify mutual interests, and expand dialogue and cooperation that can pave the way to progress” (WHOPC, July 7, 2009). This multilateralism, according to Martel, was characteristic of Obama’s overall foreign policy after assuming office. The Obama administration wanted to reduce U.S. involvement in the world, cooperating more multilaterally with other states to solve their own regional problems (2015, p. 326-327, 328, 332). In the July 7, 2009 speech, Obama talked about the hope for multilateral cooperation in multiple areas where the interests of the U.S. and Russia overlapped. He floated the idea of a potential reset in relations with Russia, while cautiously maintaining idealist rhetoric similar to Bush’s speeches. Obama discussed “America’s interest in democratic governments that protect the rights of their people… freedom of speech and assembly… the rule of law and equal administration of justice… independent media… competitive elections… democracy” and “universal values” (WHOPC, July 7, 2009). However, Obama clearly rejected primacy and an offshore balancing grand strategy in relations with Russia. This stage was brief, as Russia was willing to cooperate with the new Obama administration and a more multilateral, less idealist stage in U.S. foreign policy towards Russia began.

The second stage in Obama’s foreign policy towards Russia, from 2009 to June 2013, decoupled democracy and human rights in Russia from U.S.–Russia cooperation. “Our two countries continue to disagree on certain issues, such as Georgia, and we addressed those differences candidly. But by moving forward in areas where we do agree, we have succeeded in resetting our relationship, which benefits regional and global security” (WHOPC, June 24, 2010). This dual-track approach used by Obama’s administration offered Russia pragmatic cooperation where the interests of both countries aligned while leaving democracy and human rights issues on a separate track. Nonetheless, this stage retained some vague references to idealism, which was not the case with the first stage in Bush’s foreign policy towards Russia, which did not use idealism at all. This stage corresponds with what many authors have written about Obama’s reset with Russia. Indyk, Lieberthal, and O’Hanlon (2012, p. 91) have labelled Obama’s foreign policy as “pragmatist when necessary.” Cox, Lynch, and Bouchet (2013, pp. 10, 27-30) argue that Obama was less keen on democracy promotion then the previous Bush administration; however, Obama did not abandon idealism in U.S. foreign policy. Obama’s emphasis on both cooperation and idealist values followed liberal internationalist logic. As U.S. Vice President Joe Biden put it, the idea behind cooperation with Russia was to make Russia more like the West: “History shows that in industrialised societies, economic modernisation and political modernisation go hand-in-hand. You don’t get one without the other” (The White House Office of the Vice President. March 10, 2011). This indicates that pragmatic cooperation with Russia was motivated by the liberal internationalist idea that the U.S. should integrate non-democratic states in the U.S. led international system (Haass, 2005, p. 19, 25). While the Bush administration thought that democratisation would lead to cooperation, the Obama administration thought that cooperation would lead to democratisation. Both were wrong. This did not happen.

Even before Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, relations between the two states had deteriorated and Obama’s foreign policy towards Russia had begun to change. In the third stage of foreign policy towards Russia, as problems arose in relations between the two countries, the tone that Obama used about Russia changed in August 2013, returning to the idealist grand strategy element: “a number of emerging differences that we’ve seen over the last several months around Syria, around human rights issues, where it is probably appropriate for us to take a pause, reassess where it is that Russia is going, what our core interests are, and calibrate the relationship.” Obama still talked about “hope” of potential cooperation, but idealism dominated far more than in previous speeches. For example: “Nobody is more offended than me by some of the anti-gay and lesbian legislation that you’ve been seeing in Russia” (WHOPC, August 9, 2013). The reset of relations between both states was over even before Russian aggression in Ukraine.

The fourth stage in Obama’s foreign policy towards Russia commenced after Russia’s aggression in Ukraine in March 2014. In response to this crisis, Obama talked about using the full spectrum of grand strategy instruments, except unilateralism. In these statements, Obama twice spoke about U.S. leadership, which “has mobilised the international community in support of Ukraine to isolate Russia for its actions and to reassure our allies and partners” (WHOPC, March 17, 2014). He also invoked idealism: “Dignity… every human being is born equal, with free will and inalienable rights… justice… might does not make right… democracy… a government’s legitimacy can only come from citizens… freedom… it’s inevitable, not because it is ordained, but because these basic human yearnings for dignity and justice and democracy do not go away” (WHOPC, September 03, 2014). Non-military tools were discussed as well. Obama was talking about “imposing costs through sanctions that have left a mark on Russia and those accountable for its actions. And if the Russian leadership stays on its current course, together we will ensure that this isolation deepens. Sanctions will expand” (WHOPC, March 26, 2014). However, he still discussed potential cooperation with Russia: “Since the end of the Cold War, we have worked with Russia… we believe the world has benefited when Russia chooses to cooperate on the basis of mutual interests and mutual respect” (WHOPC, March 26, 2014). Obama’s speeches even included one mention of offshore balancing burden sharing element: “in a world of challenges that are increasingly global, all of us have an interest in nations stepping forward to play their part -- to bear their share of the burden and to uphold international norms” (WHOPC, March 26, 2014).

Most significantly, support for military power in foreign policy towards Russia, which is supported by primacists, constantly appeared in Obama’s speeches as well: “America’s support for our NATO allies is unwavering. We’re bound together by our profound Article 5 commitment to defend one another… We’ve already increased our support for our Eastern European allies, and we will continue to strengthen NATO’s collective defense…” (WHOPC, March 20, 2014). Up until 2014, NATO was relatively rarely discussed in speeches about Russia by both Bush and Obama. The increased emphasis on NATO in speeches after 2014 is a significant indication that the U.S. grand strategy towards Russia shifted towards primacy, because primacists emphasise the military security dimension of NATO in relations with Russia (Posen and Ross 1996, p. 37). This was a unique change compared to all previous statements. Such change did not occur after the Russia – Georgia war. This indicates that Obama was leaning towards primacist grand strategy towards Russia in this period. However, although Obama discussed military power, a primacist grand strategy element, he did not support unilateral foreign policy. Liberal internationalists are critical of primacist unilateralism, the idea that the U.S. can solve international problems by working alone or with coalitions of the willing. Firstly, it is also perceived as arrogant by other states and diminishes U.S. soft power (Nye 2002). Secondly, complex contemporary global challenges often cannot be solved by the U.S. working alone and require cooperation with other states (Brooks et al. 2013, p. 141; Finnemore 1996, p. 158). Although throughout the presidency of Barack Obama, liberal internationalist grand strategy – idealism, multilateralism and non-military power – dominated in U.S. foreign policy towards Russia, in the first three stages up to 2014, after Russian aggression in Ukraine, Obama’s speeches embraced the military power element and shifted towards primacist grand strategy.

Conclusions

U.S. foreign policy towards Russia from 2001 to 2017 is an important topic from a security perspective for NATO’s eastern flank countries. Liberal internationalist and primacist grand strategies offer insight into the logic that has guided and still guides U.S. foreign policy towards Russia. The U.S. grand strategies – primacy, liberal internationalism, and offshore balancing – were operationalised as a sum of four different elements describing various aspects of U.S. foreign policy – leadership, values, cooperation, and power – and were used in the coding process of speeches. The results of the coding and classification of 36 units of analysis – speeches by U.S. presidents and Vice President Joe Biden – according to this classification framework allowed for the evaluation of which grand strategy and which grand strategy elements the U.S. used towards Russia from 2001 to 2017. This allowed the grand strategy U.S. used and various stages in U.S. foreign policy towards Russia to be identified in order to answer the research question.

According to the analysis of the speeches of George Bush, Barack Obama, and Joe Biden, up to March 2014, the grand strategy that Bush and Obama implemented in relations with Russia was liberal internationalism. Although the emphasis on multilateralism and the role of idealist values changed over the years, overall this approach supported multilateral leadership, idealist values and the use of non-military instruments in foreign policy towards Russia. This approach lacked primacist unilateralism and military power elements. The absence of these elements makes this strategy towards Russia unique. It was different from the militarised containment strategy during the Cold War and different from the strategy U.S. has used towards Russia since March 2014.

During this liberal internationalist period, the emphasis in U.S. strategy towards Russia shifted from multilateral cooperation to idealism and back multiple times. The first stage in the foreign policy of the Bush administration towards Russia from 2001 until mid-2003 emphasised multilateral cooperation with Russia in order to address various global problems. The second stage shifted towards the idealist grand strategy element and lasted until mid-2006. Using the linkage strategy, Bush connected democracy and the human rights situation in Russia with cooperation between the U.S. and Russia, promising increased cooperation if Russia democratised. This approach did not deliver and Bush criticised the lack of democracy in Russia increasingly and relations between both states deteriorated. Starting with mid-2006, the third stage – the drift – in relations between the U.S. and Russia began and included short, vague speeches with less grand strategy elements than other speeches before and after this period. This drift ended in early 2008 when the fourth stage – Bush’s reset – started. Bush returned to a positive, multilateral agenda of cooperation with Russia, abandoning idealist values. This stage is often missing in the analysis of Bush’s foreign policy towards Russia. However, the Russia-Georgia War in August 2008 stopped this brief period of positive rhetoric. After this war, the fifth stage started, where Bush returned to idealist values and talked about the use of non-military foreign policy tools as well as multilateral cooperation; however, this time not with Russia, but against Russia.

The emphasis on multilateral cooperation or idealism continued to change during first three stages of Obama’s foreign policy towards Russia. The first stage was about potential multilateral cooperation with Russia on issues where both states had similar interests with references to idealism similar to Bush’s speeches in 2009. Second, Obama’s reset with Russia used the dual-track approach towards Russia. This approach separated multilateral, pragmatic cooperation in areas where the interests of both countries aligned, from idealist values and problems with democracy and human rights in Russia. This followed the liberal internationalist logic that Russia would see the benefits of increased cooperation with the U.S. that would become possible if Russia democratised. However, unlike Bush’s purely multilateralist first stage, this stage kept some occasional vague references to idealism. Nonetheless, this approach did not deliver either and in the third stage, starting from August 2013, the reset of relations was over before Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. Obama returned to increased emphasis on idealism similar to Bush’s second stage.

Although the containment grand strategy towards the Soviet Union during the Cold War can hardly be compared to the current U.S. strategy towards Russia, there are some similarities. During the containment, the emphasis in relations with the Soviet Union shifted from idealism to cooperation as well. There were periods of more pragmatic cooperation with the Soviet Union, for example, détente – relaxation of hostilities during the Richard Nixon administration starting with 1968. This less militarised, more diplomatic version of containment attempted to engage the Soviet Union in order to create mutually beneficial “structure of peace” to the Cold War through negotiations on specific issues which led to the SALT I arms control treaty and the Helsinki Accords (Gaddis 2005, pp. 278, 287, 290). During the containment, there were also periods with emphasis on using idealist rhetoric against the Soviet Union. For example, the “ideological offensive” of Ronald Reagan starting from 1981 which abandoned more pragmatic cooperation with Soviet Union and embraced tough, idealistic rhetoric about democratic values, criticising human rights violations and lack of democracy in the Soviet Union (Gaddis 2005, pp. 351-354; Martel 2015, pp. 289, 294). There were similar patterns during the Bush and Obama administrations. This swinging pendulum from idealist to cooperation rhetoric was an important characteristic of the U.S. foreign policy towards the Soviet Union and still applies to U.S. strategy towards Russia. This pattern should not be forgotten by the countries on NATO’s eastern flank.

Russia’s aggression in Ukraine in March 2014 marked not only the fourth stage in foreign policy towards Russia, but also an end to the pure liberal internationalist grand strategy which the U.S. had used towards Russia so far. Previously, the primacist military power grand strategy element in relations with Russia had only appeared on rare occasions, but now it played a prominent role. Since the 1990’s, primacists had been critical about Russia and they had discussed deterrence and the role of NATO as the pillar of military security in Europe. These primacist arguments now appeared in Obama’s speeches. Such a change did not occur after the Russia – Georgia War or after the change in U.S. administrations. The new approach Obama used was a mix of primacist and liberal internationalist grand strategies. Although Obama did support the primacist military power element in U.S. foreign policy towards Russia, he also supported the use of all other grand strategy elements and his approach lacked a primacist unilateralist element. Obama emphasised non-military power, an idealist approach in relations with Russia, multilateral cooperation against Russia and occasionally even the burden sharing element of offshore balancing. The last stage was a unique period in U.S. foreign policy towards Russia with elements not present during Bush’s presidency and the first three stages of Obama’s foreign policy towards Russia. After 2014, the U.S. grand strategy towards Russia outlined in the speeches changed as Obama embraced the primacist military power element in relations with Russia.

This U.S. grand strategy – liberal internationalism with an increasing primacist military power element towards Russia, correlates with the “Flexible Response” period during containment. During the Cold War, the U.S. used a spectrum of approaches to deter the Soviet threat – some more, some less militarised. The flexible one was in between both. More militarised than only relying on nuclear weapons for deterring the Soviet Union, but not using the military to roll back Soviet influence. The flexible response of John Kennedy after 1960 was about strengthening both conventional and unconventional forces as well as non-military tools of U.S. foreign policy. The goal of this approach was to expand the range of possible U.S. responses to the Soviet provocations: to increase the “number of escalatory steps that could be taken prior to resorting to nuclear weapons” (Gaddis 2005, p. 214-215, 226; Martel 2015, p. 264-265). Building on the analysis of this paper, the U.S. grand strategy towards Russia starting with 2014 fits the flexible response period of containment. Obama discussed all grand strategy elements except unilateralism. Enhanced Forward Presence multinational battalion battle groups on the Eastern flank of NATO member states, as well as the increased U.S. presence in the region through various aspects of the European Deterrence Initiative increase the number of escalatory steps that the U.S. can use to respond to Russian provocations using military and non-military means. The flexible response starting with the Kennedy administration is the historical period that should be the focus of analysis to understand current U.S. grand strategy towards Russia and the role of states affected by it.

Evaluating the analytical framework used in this research, the grand strategy classification framework offers a valuable tool for analysing, classifying and identifying different foreign policy stages. The classification not only allowed for the clear identification of various periods in U.S foreign policy towards Russia which have also been described by other authors, it also identified a period which is often neglected in the descriptions of U.S.-Russia relations – Bush’s reset – an attempt to restart cooperation with Russia before the Russia-Georgia War in 2008. This content analysis also allowed for the specific pinning down of the moment when U.S. grand strategy towards Russia changed. For example, while Bush positioned democracy promotion as a central element in his grand strategy starting in 2002, this idealist element only appeared in June 2003 in relations with Russia, when Bush linked democracy in Russia with positive relations with the U.S. Furthermore, Obama’s reset in relations with Russia was already over in August 2013 even before Russian aggression in Ukraine.

The grand strategy classification framework offers a systematic coding process which allows for the transformation of speeches and documents into quantitative data which can be measured, to determine the support for each grand strategy element within any source. This analytical framework should be used in further research for the content analysis of other speeches and statements of the key people behind U.S. foreign policy, U.S. National Security Strategies and other policy planning documents because it is possible that the speeches used in this research were not representative of the whole U.S. strategy towards Russia. Nonetheless, the content analysis of these speeches indicates that ideas of liberal internationalist and increasingly primacist grand strategies do influence U.S. foreign policy towards Russia. By focusing on these strategies, both scholars and policymakers can understand U.S. foreign policy towards Russia better.