Introduction

The social structure is hierarchical, i.e. its certain elements are subordinate to others – located higher in the hierarchy. Occupying a specific place in the hierarchy is associated with diversified access to resources: money, power, prestige etc. The grouping of society is referred to as social stratification. The social structure is governed by four major elements according to which the society is divided, namely: classes, strata, professional and demographic structures.

The characteristic feature of the contemporary security environment is that the boundaries between its internal and external dimensions, military and non-military that were once explicitly clear-cut have now become blurred and indistinguishable. Globalisation and growing interdependence often result in the emergence of unpredictable phenomena, whose scope is by no means limited by geographical or political barriers and economic systems. Military challenges and threats are still present. The security of our country is inevitably reliant on its ability to act effectively, according to national interests, and to achieve strategic goals in the current and forecast security conditions. These activities should be particularly focused on taking the arising opportunities and fulfilling internal and external challenges, which are a consequence of mutually interacting political, military, economic, demographic and environmental processes and phenomena. Coping with these challenges requires an efficiently organised and managed state security system, one of the key constituents of which are armed forces. A professional military is the key indicator and factor of the defensive capabilities of the state. Therefore, not only must the army be supported by modern equipment and highly trained personnel, but it is furthermore essential that its disposition and staffing be at an adequate level. Past observations indicate that there exists a certain correlation between elements of the social structure and the manpower of armed forces. The issue then is to determine the model of the social structure that will be the most beneficial to securing the undisturbed and optimal functioning of the Armed Forces, thus affecting the security of the state.

Elements of social structure

In a broad sense, the class structure is understood as a division of society into classes, based on economic differences. The class structure of this type refers to the concept proposed by Karl Marx. The place occupied in given classes is determined by access or lack of access to possessions or certain means of production. According to Marx, the division not only affected the economic dimension of life but also had a bearing on other dimensions e.g. access to education, to power, and lifestyle. In contemporary reality, this is a division determined by: income, education, occupation, position or lifestyle. Although the class division is recognised, it no longer plays such a significant role. The most commonly followed division is currently three-fold, accounting for the upper, medium and lower classes.

The upper class is a narrow group of affluent citizens that includes owners of large companies, management, renowned specialists etc. People belonging to this class enjoy greater social prestige and have privileged access to various types of goods. Due to its social position, this group is highly unlikely to consider enlistment in the structures of the armed forces.

The middle class encompasses those living relatively comfortable lives – executives, medium-sized and small enterprise owners, skilled workers, freelancers, people with a stable position. In democratic countries, it is the most numerous group, exerting a profound impact on the functioning of states.

Finally, the lower class denotes poorly educated unqualified labourers, whose involvement in social life is marginal and whose living conditions are poor. The representatives of this class are often subject to exclusion and their needs disregarded. It may be safely assumed that these are the representatives of the two latter strata that would respond most positively to the offer of employment in the armed forces, which is why the focus of recruitment efforts ought to be directed particularly to this group. The conditions of employment, work and remuneration should be attractive enough to attract their interest and tempt them towards recruitment.

Social stratification refers to the division of society into strata, i.e. groups of people that are distinguished by and simultaneously share a common social position. The said division stems from the hierarchical structure of society, and the particular place occupied in the hierarchy is determined from such criteria as:

level of education: primary, secondary, tertiary;

property (assets);

occupation, the source of income (labourers, farmers, private entrepreneurs);

the scope of power exercised, e.g. the ruled, the rulers;

lifestyle;

prestige.

One of the most recognisable groups in the social strata is the intelligentsia, whose characteristic properties include higher education, a similar standard of living, lifestyle and common interests, involving e.g. culture. Nevertheless, the three major criteria considered in stratification are: wealth (class-related), prestige (social status) and power. Representatives of different strata have unequal life opportunities, dissimilar lifestyles, and typically exhibit different orientations, follow different norms and differently perceive their social position in comparison to other strata.

The professional structure shows stratification dictated by profession. An extremely important social role of every human being is to practise a chosen profession, which offers an indication of one’s education, the system of values, wealth, position and prestige within the structures of a given society. The prestige of a given profession predominantly depends on the level of remuneration and power involved; however, non-exclusively; e.g. academia and education professionals enjoy extensive and high regard in society, although the earnings in this profession are rather moderate. Given the currently observed rapid pace of change in social structures, the recognition for a chosen profession is variable, owing to the fact that new professions appear while old ones disappear.

The demographic structure, i.e. the division of society according to age groups, sex, marital status, place of residence etc. offers the closest representation of the current state of society. It is widely regarded to be the critical element of the social structure, whose importance is crucial to the end number of armed forces, not only in Poland but also in every country in the world. It is the structure of gender and age that to the greatest extent shapes the birth rate and the growth in labour resources in a given country; its proportions determine the functioning of society and determine its model. emerging new problems, issues such as an ageing society (in highly developed countries), economic emigration, migration from small towns to large conurbations or the thriving professional activity of women significantly contribute to changes in the demographic structure of society.

Social structure of Poland

The preceding section provided a substantiated definition of what is considered as “social structure” and its constituents but the focus of this section shifts to determining the social structure of Poland. The far-reaching changes that have taken place in our society from the beginning of the nineteenth century, through wartime and post-wartime, until today, have brought about fundamental changes in the social structure.

Until the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Polish society had been typically agricultural. Rural residents constituted the dominant group of the entire population. The overpopulated village was inhabited by peasants subsisting on the verge of poverty – the most numerous group being farmers, owners of small farms or without their own farms. At that time, migration from the village to the city occurred spontaneously. Labourers were the next largest social class in Poland. It was established mainly in large cities such as Warsaw, Łódź, Poznań and the cities of Silesia, where industry was flourishing. The situation of this social class was difficult: on top of low salaries, barely sufficient to provide for a small family, working conditions were poor and the working day long. Their situation was aggravated by inadequate housing and sanitary conditions in overcrowded cities. On the other hand, the situation of white-collar workers, the intelligentsia and the lower middle class, i.e. craftsmen and small shop owners, was slightly better. The groups that could enjoy the highest standard of living were the landowners and owners of employment establishments. The pre-war society was closed and largely separated; hence, the transition from one social class to another was rather unattainable. Poles, however, slowly began to follow the path that led to transformation into a modern industrial society.

The period between1945 and 1960 saw the most extensive changes in Polish society and its structure, which can be traced back to several roots: as the first, the result of large-scale geographical dislocations, which were the consequence of national border changes, the second, the migration from the countryside to the city, spurred by industrialisation processes. During this period, the social structure also changed dramatically. This was mainly caused by initiatives on the part of the authorities, such as: agricultural reform, attempted collectivisation of the countryside, nationalisation of industry and increased industrialisation of the country. Simultaneously, private ownership of the means of production was abolished, resulting in the disappearance of the upper classes: landowners and owners of the means of production. The social structure became flattened. These changes coincided with the sharp outflow of the rural population, particularly young people, to cities. The intensive development of industry triggered the rise in demand for the labour force. The system transformations eventually embraced the intelligentsia. In the pre-war Poland, the representatives of this group had come under suspicion of the contemporary authorities, which is why their position in society was actively marginalised.

The years 1960-1970 have come to be referred to as the period of “little stabilisation.” Gradually, the pace of change began to decelerate in comparison with the preceding years, but still did not cease. however, two important changes did take place. For the first time, the urban population in Poland outnumbered the rural residents. In addition, the number of workers in industry exceeded the number of workers in agriculture. Greater numbers of better-educated workers were employed in industry, which showed rising demand for specialists. In the countryside, the living conditions improved, among others through the carrying out of extensive electrification projects.

The 1970s was a decade marked by the significant increase in the role of the working class, whose tremendous social power was greatly appreciated and exploited. Admittedly, the standard of living increased. This was particularly true for industrial workers employed in large enterprises, such as miners and steelworkers. They obtained special privileges, unavailable to other workers, which was a deliberate effort of the leading party to diversify and break up the working class internally. The wages of industrial workers would frequently exceed the wages of white-collar workers.

The immensity of the changes that have taken place in Poland since june 1989 had a further significant impact on the structure of the Polish society. The transformations were fuelled by even greater access to education and the emerging diversity in property. There has been an increase in the number of knowledge workers in white-collar professions, which evidences the slow shift from industrial society to post-industrial society. Classes previously non-existent in the Polish People’s Republic have come into existence, i.e. the middle class, which occupies a place in the social structure between the working class and the upper class. A typical representative of this class is usually a small business owner, or an owner of a small employment establishment. The new middle class is composed of specialists or highly qualified experts and includes all those involved in management. A characteristic feature of representatives of this class is access to information and the use of knowledge and information. In modern information societies, this class is growing in importance. The class of entrepreneurs – above all entrepreneurs – are owners of the means of production. Although not numerous, the representatives of the middle class have managed to create their own organisations and to act effectively towards protecting their interests. The underclass is a group comprised of people leading a life of distress and destitution. It includes people who are either permanently unemployed or badly paid, and claiming benefits from social security institutions. A characteristic feature of this class is its marginalisation and complete exclusion from the mainstream of social life or not participating in it (http://www.wos.net.pl/struktura-spoleczenstwa-polskiego.html) .

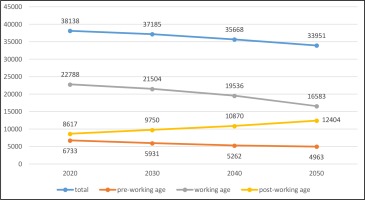

An important characteristic of the current demographic situation is that Poland’s population has been decreasing since 2012, which was preceded by the previously observed increase in the period of 2008-2011. In 2012-2016, the country’s population fell by over 100,000. The decline in the population for six years was the result of unfavourable trends, i.e. the negative rate of natural increase and the negative balance of foreign migration. According to statistical data published by the Polish Central Statistical Office, the population trends have been as follows over the last ten years (in thousands):

Fig. 1

Population of Poland 2005-2016 (based on data from the Polish Central Statistical Office, GUS)

From the above date, we can see that the gender structure in Poland is balanced. Nevertheless, the trend observed in Poland is dissimilar to global tendencies i.e. there are more women than men.

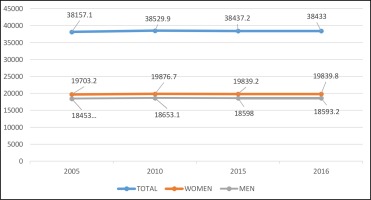

Undoubtedly, the age structure has been and will continue to be among the key factors determining the manpower of the armed forces. For over a decade, there has been an evident trend in Poland pointing to an ageing society. On the one hand, this situation may be explained in statistical terms and trends of changes in the share of the population in the post-working age, i.e. women 60, men 65+, this share increased from 14.8% in 2000 to 20.2% in 2016. however, on the other hand, this is due to the increase in the number of senile citizens (over 80 years of age) from almost 860,000 in 2002 up to 1.5 million in 2016, i.e. by as much as 70%, whose major cause is an increase in life expectancy (https://stat.gov.pl/ ).

The data in Fig. 2 does not cover the entire cross-section of the society. For the purposes of this paper, it was decided that only the selected age groups were relevant, i.e. groups that remain in the interest of the armed forces as potential candidates for military service. The data indicates trends of decreasing resources of 18-19-year-olds and people up to 30 years of age.

Fig. 2

Age structure of selected population groups in 2005-2016 (based on data from the Polish Central Statistical Office, GUS)

For many years, Poland has been predominantly a sending country; however, its status has shifted to a sending/receiving country recently. The phenomenon stems from the difference in the economic potential between Poland and Western countries. The primary source of motivation of emigrants is to begin or seek employment abroad.

Several premises for emigrating from Poland have been revealed in studies and public discussions, i.e. higher earnings, a higher standard of living, better social conditions, better career prospects, more friendly public administration, a more secure geopolitical location and a family already living or intending to live abroad.

One of the consequences of the considerable emigration of Poles in recent years, apart from the growing demographic decline, is the fact that increasing numbers of Polish children are born abroad. This is particularly evident in countries where there are favourable conditions for starting or expanding the family.

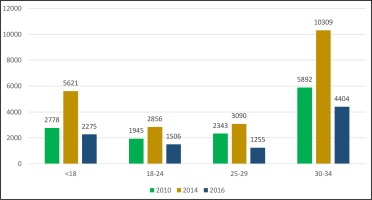

The data in Fig. 3 clearly indicates a decrease in the number of people emigrating for a period of 12 months and longer. While this may be a reflection of an improving economic situation in the country, it should appear that the restrictions implemented by european Union countries in the field of employment and social benefits as well as growing doubts about citizens’ security may have also influenced the observed developments.

Fig. 3

Emigration for 12+ months of selected population groups in 2010-2016 (based on data from the Polish Central Statistical Office, GUS)

In Poland, the proportion of the employed population, according to the data provided by the Polish Central Statistical Office, amounts to 56.2%. The value of this indicator depends on the demographic structure (the size of the productive age group), the number of employed women, labour supply and the retirement age. Over the last decades, the occupational structure of Poland’s population has experienced significant changes. The number of employees in services is systematically increasing. The population employed in services primarily deals with trade and repairs, education, real estate and business services, science, public administration and national defence, along with social and health insurance. however, this does not resolve the problem of unemployment – currently amounting to approx. 6%; although admittedly, in a year-to-year perspective, the unemployment rate in Poland has been on the decline. Among the outstanding reasons for the unemployment the major accusation might be the obsolete industry branch structure with regard to the current market needs, the overdue restructuring of the Polish economy, negligible scientific and technical progress, the emergence of new technologies resulting in the decrease in labour demand due to work automation, the need to retrain in response to the disappearance of certain professions and the emergence of new ones (e.g. financial and insurance adviser), excessive cost of labour, discouraging entrepreneurs from creating new jobs.

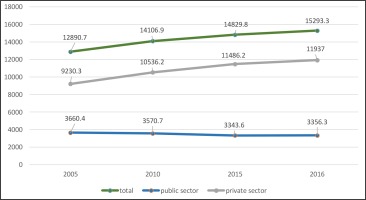

The chart in Fig. 4 indicates that over the last ten years, the number of people employed in the private sector has increased, and this branch has become more competitive in the labour market. The shift can be attributed to better working and pay conditions offered by private employers, whose businesses flourish, fostered by the government initiatives creating more favourable conditions for their functioning; on the other hand, the employment in the public sector remains invariably stable.

Fig. 4

Employment structure in 2005-2016 (based on data from the Polish Central Statistical Office, GUS)

One of the crucial factors reflecting the development of society is the constant increase in the level of education. Within a period of nine years, the dynamic changes exerted a considerable effect on the structure of the population according to the level of education.

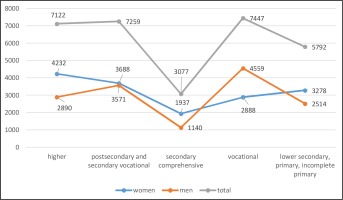

Fig. 5

The level of education in the fourth quarter of 2016 (based on data from the Polish Central Statistical Office, GUS)

The data shown in the figure above indicates that the level of education among women in Poland is higher compared to men. Furthermore, statistics show that in recent years, the level of education of Poles has been constantly increasing. Although this positive trend is seen at all levels of education, it is among people with higher education that the trend is the most outstanding. The percentage of people with secondary education remained constant,; nevertheless, the share of people with primary and incomplete primary education dropped, whereas the widespread popularity of higher education is invariable. Universities must be prepared that nowadays every other high school graduate continues their education beyond high school. On the other hand, they should also take into account the fact that their level of preparation for studies and, subsequently, the performance is bound to be significantly diverse. The continuing mass appeal of higher education requires universities to present a comprehensive educational offer in order to meet the expectations of their students. The compromise must be reached with a view to accommodating the needs of potential future members of young scientific staff, as well as of those for whom higher education is strictly vocational and is necessary insofar as finding the preferred place on the labour market is concerned.

The demographic vision of the country that emerges from the latest population forecasts is largely unsurprising. Poland is to face a further gradual loss of population and significant stratification according to age factor. both these facts result from the well-explored mechanisms of connections between the numbers of births and deaths and the population status. Poland has found itself in such a moment of demographic development that even an increase in the fertility rate to a level straightforwardly guaranteeing replacement of generations in the short term will fail to reverse these ongoing processes and to counteract the population decline. With such a significant distortion in the population structure, the process of demographic reconstruction is time-consuming and requires consistent, long-term actions. In 2050, the population of Poland is projected to be 33.95 million. In a like-for-like comparison with 2013, this would mean a reduction in the population by 4.55 million, i.e. by 12% (https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/prognoza-ludnosci/prognoza-ludnosci-na-lata-2014-2050-opracowana-2014-r-,1,5.html ).

As shown in the preceding figure, the decline in the population of Poland and the ongoing ageing of society will result in an increase in the number of post-working age population, and thus in the pre-working and working age, which will be a pivotal factor shaping the labour market and, by extension, the size of the armed forces.

Armed forces

The Armed Forces play a special role and occupy an important place in the structures of a state. They may be seen as an essential tool of public authority, which is entrusted with the purpose, missions, functions and tasks derived from norms established by the authorities, determining the entire sphere of their functioning, including their existence and operation. even Plato communicated the need for a bigger state, “not by a little but by an entire army, which will come out and fight the invader” (Plato 2003), for us and all that is ours. All known systems of governance are to a varying degree maintained by the authorities by means of coercive measures, through the law-enforcement security forces such as the army and the police. Coercive measures at the disposal of the armed forces may serve various political purposes. Armed forces are undoubtedly a guarantee of the power of the state, its duration and development.

The special features of the armed forces, which combine their strength, teamwork and discipline, is that they are employed to guarantee political order, stability and obedience to the law as well as the security of structures of political power. however, over the last few decades, the use of military forces to counteract and resolve the havoc ensuing from the outbreak of natural forces or the effects of human activity has become increasingly accepted. The primary reason is that civilian forces subject to public and non-governmental administration are incapable of handling the fight against natural disasters, technical failures and catastrophes, terrorist attacks, state border violations and other threats. Therefore, the military is a suitable resource to counter terrorism, fight floods, ice phenomena and the effects of drought, search and rescue, remove effects of conflagration, handle unexploded ordnance to name but a few. These and other circumstances for the use of the army to support civil authorities and communities, however, may only occur on the condition that the armed forces are not involved in execution or preparation of expeditionary missions or limited to a critical minimum. Maintaining active armed forces and their reserves is inseparable: the fewer soldiers in active service, the greater must be the mobilisation capabilities of the armed forces reserve and, in principle, of the whole country. The army as a public instrument serves the national interest, including the sphere of building national, state and cultural identity, as well as in the fields of teaching, education and fostering. Although not all citizens pursue a career in this honourable service (which nota bene does not necessarily have to take the form of professional military service), there exists a commonly shared attitude to soldiers’ craftsmanship as a conscious willingness to sacrifice life for the greater good of the homeland. The credo of fundamental virtues determining the life of soldiers is rooted in patriotism, justice, honour, integrity, courage, bravery, deep respect for humanitarianism and the value of human life. It is, therefore, common to recognise the social role of the army as a separate part of the nation obliged to defend itself from aggression and to observe national freedoms. however, in order to promote the atmosphere of uniqueness, the state is obliged to create special conditions for members of the armed forces so that they could feel the prominence of their service.

The legal basis for the functioning of the Polish armed forces follows from the provisions of the Act on the General Defence Obligation of the Republic of Poland, whose Article 3 states that “The Armed Forces of the Republic of Poland are guarding the sovereignty and independence of the Polish Nation and its security and peace (...) The Armed Forces may also act in response to natural disasters to eliminate their consequences, perform anti-terrorist activities and activities for the security of property, conduct search and rescue operations and for the protection of human health and lives, handling unexploded ordnance or dangerous materials, including their neutralisation, and as part of crisis management.” And furthermore “In the execution of constitutional tasks in the field of safeguarding the state’s independence, the integrity of its territory and ensuring security and the inviolability of its borders, The Armed Forces have the right to use means of direct coercion, the use of arms and weapons, accounting for the necessity and purpose of performing these tasks in a manner proportionate to the threat and within the limits set out in the binding international agreements and international customary law (Act of 21 November 1967 on General Defence Obligation of the Republic of Poland”).

Military manpower planning

The Armed Forces of the Republic of Poland are the foundation of the national defence system. The current number of professional soldiers enlisted in the Polish army is 105 thousand, and its composition, i.e. the number of permanent personnel and the total number, is set out in several legal acts and documents influenced by individual government agencies, competent in matters of national defence. These documents are, inter alia:

Act of 25 May 2001 on Restructuring, Technical Modernisation and Financing of the Polish Armed Forces;

Key directions of the development of the Armed Forces and their preparation to defend the State - introduced by the decision of the President of the Republic of Poland;

Detailed directions for reconstructing and modernisation of the Polish Armed Forces for years ... – implemented by the resolution of the Council of Ministers, every 4 years for a 10-year planning period, based on the Key Directions of the Development of the Armed Forces;

Guidelines of the Ministry of National Defence on planning and preparation to defend the State in the Ministry of National Defence;

Armed Forces Development Programme (published in a 4-year planning cycle, introduced by the Regulation of the Minister of National Defence, based on Key Directions of the Development).

Due to the changing conditions of the security environment and the identified needs, the management of the Ministry of National Defence made a decision regarding increasing the manpower of armed forces, which was reflected in the amendment to the Restructuring, technical Modernisation and Financing of the Polish Armed Forces, whose third article reads “The number of the Armed Forces amounts to no more than two hundred thousand permanent soldiers.” Within this number, no more than one hundred and fifty thousand are intended for professional soldiers. The lack of a formally binding document, which would clearly determine the planned permanent and total number of military personnel of the entire armed forces and particular staff corps, considerably hinders the planning of the policy in the aspect of shaping the human resources in the long-term perspective. As a result, the number of current military personnel resources is contingent on the budgetary decision of the Minister of National Defence. Under such circumstances, it emerges that this distinct lack of normative-planning documents defining the target model and the manpower of the armed forces, of particular staff corps and services effectively blocks attempts to develop short or long-term permanent and total employment statuses of professional soldiers, both in the short- and long-term perspective. The documents in question should guarantee the securing of the adequate budgetary resources necessary to maintain the professional and non-professional personnel in the amount set out for the number of full-time positions and allow a departure from average annual accrual, as is currently the case, on the basis of the budgetary decision of the Minister of National Defence.

Military service – types and sources of recruitment

In Polish legislation, two normative and executive acts regulate military service i.e.:

Act of 21 November 1967 on the General Defence Obligation, which applies to non-professional soldiers;

Act of 11 September 2003 on the Military Service of Professional Soldiers.

The provisions of Article 4 Paragraph 1 of the Act on the General Defence Obligation determine that “all Polish citizens capable of defence due to age and state of health are obliged to perform this duty.” Article 58 of this Act precisely sets out the age limits: “The duty of military service, to the extent specified in this Act, shall apply to Polish citizens, starting from the day on which they turn eighteen, until the end of the calendar year in which they finish fifty-five years of age and with regards to officers or non-commissioned officers – sixty-three years old.”

Pursuant to the provisions of the Act on General Defence Obligation, the duty of military service consists in:

completing military training by:

serving preparatory service by

serving territorial military service by soldiers;

serving periodic military service by reserve soldiers.

In the event of a threat to the security of the state, if it is essential to ensure the possibility of executing tasks related to the purpose of the Armed Forces, the military service duty furthermore includes:

performing compulsory military service by individuals subject to this obligation;

completing military training by university graduates.

Resulting from the provisions of the amendment to the Act on General Defence Obligation in 2009, the last general conscription occurred in 2008, thereafter conscription was suspended. The setting of the date of commencement and duration of the obligation to serve military service and complete military training is part of the powers of the President of the Republic of Poland, who does so at the request of the Council of Ministers.

There is a great difference between service during peacetime and during mobilisation or war. In the latter two cases, the duty of military service encompasses:

people subject to military entrance processing;

reserve personnel, including reserve soldiers;

soldiers on active military service;

others who apply to this service through volunteer recruitment.

The Act on the General Defence Obligation of the Republic of Poland imposes an obligation to defend on all Polish citizens capable mentally and physically of performing this duty. Therefore, the legislator has defined the following categories of fitness for active military service:

category A - capable for active military service, i.e. ability to perform a specific type of active military service, as well as the ability to serve in civil defence and substitute military service;

category b - not capable for military service for a determined period of time, i.e. a temporary health impairment or acute or chronic illness, which will alleviate or recede in the period of up to twenty-four months from the date of the medical examination, thus resulting in regaining the capacity for military service in peacetime;

category D - incapable of active military service, in peacetime, except for certain service posts within territorial defence forces;

category e - permanently and completely incapable of performing active military service, during peacetime, in the event of mobilisation and during war.

If there is an emergency during peacetime, reserve soldiers may be assigned to service posts that are specified in the organisational document of a designated military unit, including posts already filled. The condition for receiving a disaster response assignment is the conclusion of a contract to perform duties within the National Reserve Forces between the commander of a military unit and a reserve soldier, a soldier in active military service, a soldier performing permanent military service or candidate service who volunteered to perform duties under the National Reserve Forces and fulfils the eligibility conditions.

Individuals who are eligible for compulsory military service (NB the service is currently suspended) are appointed according to the category assigned by the decision of the competent medical commission and, if required, a certificate of psychological fitness, professional qualifications and those subject to military entrance processing who have volunteered for service. Compulsory military service includes individuals capable of military service, who are eighteen years of age and have volunteered for service. The duration of the compulsory military service is nine months.

University graduates, including the graduates of foreign universities, are required to undergo military training (currently suspended). Military training of university graduates takes place in military units for a period of up to three months.

Volunteers whose military status is reserve as well as others not subject to the obligation of compulsory military service or military training may perform the preparatory service at request or with consent. The employment relationship pertaining to the preparatory service is established by appointment and on the basis of voluntary reporting for service. In order to be eligible for appointment to the preparatory service, a volunteer must meet certain mandatory requirements: they must be at least eighteen years old, hold Polish citizenship, fulfil physical and psychological standards for active military service, and their criminal record may not include premeditated crime; furthermore, the suitability of candidates for given corps is determined by their level of education:

at least higher – in the case of the commissioned officers education programme;

at least upper secondary or upper secondary trade school – in the case of the non-commissioned officers education programme;

at least lower secondary or eight-year primary – in the case of the enlisted education programme.

Soldiers of the preparatory service are trained in military schools and training centres.

Another type of service in the Polish Armed Forces is the territorial Defence Forces (tDF). Individuals eligible for this type of service must request or give consent to the service, their military status is reserve, and they are not subject to the obligation of compulsory military service or military training; as well as those who would be subject to compulsory service or training should the compulsory military service be put back in force. territorial military service is performed in military units and organisational cells of the territorial Defence Forces and in the Command of territorial Defence Forces. The duration of territorial military service ranges from one to six years and can be extended further. The service relationship pertaining to territorial military service is established through the appointment, on the basis of voluntary reporting for service.

TDF soldiers are assigned to service on a rotational or disposable basis. Rotation service is carried out by a soldier in a military unit, on dates of service specified by the commander of the military unit, at least once a month for a period of two days in non-working hours. territorial military service of the tDF soldier can also be rotated on other days. The disposable territorial military service of tDF soldiers is performed outside the military unit, maintaining readiness for rotational service at any time and place ordered by the commander of the military unit. tDF soldiers may be appointed for candidate service or professional military service based on identical terms specified for soldiers of the reserve; however, their candidature is approached on priority terms under the condition that they served territorial military service for a period of at least three years.

Periodic military service is performed in cases justified by the needs of national defence, of the Armed Forces or pertaining to crisis management, combating natural disasters and their consequences, anti-terrorist activities, property protection, search and rescue or protection of human health and life, cleaning up areas of explosives and other hazardous substances of military origin and their disposal, as well as the performance of tasks by the Armed Forces in remote locations. temporary military service is performed in military units and organisational cells of the territorial Defence Force, and in the case of appointment or deployment to service outside Polish borders, also in official posts or military functions away from the military units or cells. The duration of temporary military service may not exceed a total period of twenty-four months.

The Polish Armed Forces are currently facing an urgent task to replenish human resource reserves, which requires the development of long-term systemic solutions including e.g. an effective enrolment system. The system provides a greater influx of junior reserve soldiers, in particular officers and non-commissioned officers, trained within Legia Akademicka (the Academic Legion).

As in 2003–2008, the training is divided into the theoretical part – taken at universities during the academic year, and a practical part – carried out in units, training centres and military centres.

Voluntary training of students falls under Article 100 Paragraph 1 and 1a of the Act of 21 November 1967 on the General Defence Obligation of the Republic of Poland, which specifies that the duty of military service of reserve soldiers in peacetime consists in attendance in military exercise and temporary military service, while for members of non-soldier reserve this obligation consists solely of military exercises. The training process is organised and executed by specialised didactic cells, whose necessary didactic and scientific potential is geared towards the specificity of military training.

Having passed the theoretical test and after filing the application (through university administration), student volunteers receive military training cards, which entitle them to attend the practical part of training, implemented in selected military units, military education units and training centres of the Polish Armed Forces over the summer break period.

In order to be eligible to become a professional soldier, one must be a person with Polish citizenship, of unblemished reputation, whose loyalty to the Republic of Poland is beyond doubt, and who has appropriate qualifications and physical and mental capacity for professional military service. Professional soldiers constitute the professional personnel of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Poland and are divided into:

According to the provisions of the Act on the Military Service of Professional Soldiers, professional soldiers are soldiers in active service performing it on a permanent or contractual basis. The service relationship of a permanent service soldier is established through appointment on the basis of voluntary reporting for service. The service relationship of a contractual soldier is established by appointment on the basis of a contract concluded between a volunteer for the service and the competent authority.

In addition, it should be mentioned that representatives of other organs of national security can apply for a transfer to the professional military; this applies to Police, border Guard, Government Security bureau, State Fire Service, Prison Service, Internal Security Agency, Intelligence Agency, Military Intelligence Service, Military Counterintelligence Service and State Protection Service. The transferee is appointed to a position classified in military rank equivalent to the degree possessed in the original service.

The impact of demographics on Polish military manpower

The deteriorating demographic situation, stemming from the decreasing birth rate and economic emigration, is becoming an increasingly serious challenge for Poland’s development, as it is for the decision-makers of the Ministry of National Defence. As described in the preceding sections of this work, the demographic structure stands for the division of society according to age groups, sex, marital status, occupation, education, place of residence, etc. Analysing the criteria and conditions for military service enrolment, the obvious conclusion is that the demographic structure of society is central to the count of armed forces personnel, in both times of peace and war.

Data presented by the Polish Central Statistical Office (GUS) is far from optimistic considering current and projected population trends should no proper action be initiated by state authorities to curb the intense demographic decline. According to data for 2016, the total population in Poland is approximately 38.5 million. however, in the next decades, the population of Poland is expected to decrease to approx. 34 million by 2050 (http://demografia.stat.gov.pl/bazademografia/Prognoza.aspx ). Invariably for several decades, women have been shown to outnumber men. Although the difference is not significant, this carries important implications for the size of the armed forces. The vast majority of military personnel are admittedly men: women currently account for a mere 6% of the total number of registered professional soldiers. The discrepancy in the number of women and men in Poland may be partly attributed to the fact that the average life expectancy is higher in women – in 2016 approx. 82 years, while an average man is expected to live for 74 years. Among other relevant factors, there is the fact that women tend to perform lighter jobs that put less pressure on the body. While the numbers of the general population may be to a certain extent managed, the gender structure of the society is not. taking into account the dramatically low birth levels, it is necessary to intensify an effective demographic policy. It is advisable to undertake comprehensive actions aimed at promoting ideal work-life balance and strengthening the institutional support of parenthood by securing places in nurseries and kindergartens. Women still appear worried about losing their job due to motherhood. Despite the legally guaranteed employment of mothers returning from maternity/parental leave, they are still being dismissed from their jobs. The issue in question requires proper consideration and an active search for effective solutions in order to reverse the negative demographic trends and to increase the human resource levels for military service. Therefore, it is in the interest of the Ministry of National Defence to provide pro-active support for the government-led efforts to improve the demographic structure of the Polish society. Since the actual scope of this work embraces the exploration of the dependence of the armed forces on the social structure, the potential directions and areas on which the department could focus will only be enlisted: securing jobs for spouses, recreating military nurseries and kindergartens, securing housing, stabilisation of military service conditions, and medical protection. It seems that the government programme 500+, which reduces poverty and allows consumer needs to be fulfilled, may not be sufficient a measure to trigger the rise in the number of children born per woman. Therefore, it is necessary to increase efforts to meet the current challenges of family and population policy.

Low population growth means that Polish society is aging, which also has a negative impact on the manpower of the armed forces: as shown by annual analyses, the average age in the military is constantly increasing, and is currently at an approximate level of 35.5. The present state has been undoubtedly influenced by the decision of the Minister of National Defence to lift the limited period of service performed by contract soldiers to 12 years.

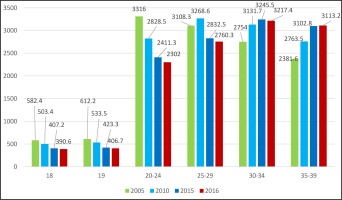

The analysis of the population structure by age indicates that the number of potential candidates for military service is decreasing. In the circle of the greatest interest of the armed forces are people between the ages of 18 and 34. beginning a military career in this age range makes it possible for soldiers to obtain a pension entitlement. In accordance with the provisions of the Act of 10 December 1993 on Retirement Benefits for Professional Soldiers and Their Families, professional soldiers appointed for the first time to serve after 31 December 2012 will become entitled to a pension after reaching the age of 55 and 25 years in the Polish Army. Data obtained from Polish Central Statistical Office (GUS) indicates that in the last ten years, the population of 18-year-olds and 19-year-olds fell by almost 1/3 (https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/roczniki-statystyczne/roczniki-statystyczne/rocznik-statystyczny-rzeczypospolitej-polskiej-2017,2,17.html ). Moreover, no improvement has been observed in trends among 20-year-olds, where in almost every period studied, i.e. 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2016, their number decreased. The exception is 2010, when there was a slight increase in the number of people aged 25-29 from 3,108.3 in 2005 to 3,286.6 which was followed by a drop to 2,832.5 in 2015. The continuing downward trend in the groups of people on the edge of critical decisions regarding their future work and life greatly affects the difficulties in managing the personnel levels in the armed forces. The situation in the group of people aged 30-34 is definitely different: in the analysed periods, there is a clear upward trend. bearing in mind the possibility of acquiring pension entitlement, for this group, this is the last moment to make a decision whether to join the ranks of the armed forces. The last analysed group is citizens aged 35-39. This section of the population, similarly to the preceding one, exhibits a growing trend. Nevertheless, in the said group only former professional soldiers constitute a valuable (in fact any) acquisition for the armed forces. The group comprises former soldiers covered by the pension system, according to which, fifteen years of service is sufficient for a professional soldier to acquire pension rights.

From the presented data and analyses, it becomes evident that the human resource becomes a valuable asset and the object of considerable fight in the labour market: whoever offers better conditions wins.

Another element critical from the position of demographics is the international migration of the population for a minimum period of 12 months. The data presented by the Polish Central Statistical Office (GUS) show that the emigration of Poles is somewhat on the decrease, which from the viewpoint of the armed forces is by all means favourable.

The occupational structure shows distinct social diversity according to profession. An extremely important social role of every human being is to follow a career in a chosen profession, on the basis of which it is possible to infer on education, the system of values, the wealth of a person, their position and prestige in a given society. At present, the military is primarily regarded as a good profession. On the labour market, a stable salary with bonuses for long service and housing benefits is definitely eye-catching. employment in the public sector comes with peace of mind and stability of employment, unlike in private businesses where the lack of orders may lead to job loss on a day-today basis. An additional value is the prestige of the uniformed service, which used to enjoy a much lower social recognition than it does nowadays. today, the confidence level in soldiers is notably higher – soldiers are treated with respect. employment in the army may not be the lightest, but surely, the conditions have improved significantly. The primary focus is on training people and the implementation of new technologies. Against other professions, the Polish soldier’s remuneration is at a decent level. The salary of professional soldiers consists of basic salary and bonuses, such as: special allowance – for special character and conditions of professional military service, service allowance – for service in certain command/management, self-contained positions or in particular military units, an allowance for long-term military service, incentive pay for professional soldiers serving in commissioned and non-commissioned corps who have an appropriate qualification and have been awarded for a top evaluation report, a functional allowance and compensatory additional payment (Act of 11 September 2003 on Professional Military Service, Article 80). The professional soldier is also entitled to other financial benefits, such as the soft landing bonus, additional annual salary, prizes and allowances, service anniversary awards, travel and business transfer bonuses, holiday payments and many other arising from military service. In addition, there is a system of bonuses for service in a specific military unit or performing tasks at specific posts. The most important goal of the remuneration policy should be to attempt to match the salaries received by professional soldiers in Poland to the salaries received by soldiers in highly developed countries – NAtO member states. All tasks carried out in the sphere of shaping the system of remuneration of professional soldiers should aim to improve the terms of service so as to create a more attractive offer in all the corps of military personnel. The said activities are intended to reinforce the motivational function of remuneration, thus translating to the stable acquisition of highly qualified personnel for professional military service and the maintenance of highly qualified soldiers in service. Nevertheless, in order to attain this goal, it is imperative that appropriately high financial resources are allocated to enable the creation and maintenance of a competitive level of salaries for professional soldiers, which would dwarf the salaries of other uniformed services and are generally available on the civil labour market. It is particularly important in the face of declining levels of human resources available on the labour market and increasing employment in the private sector. The Polish Central Statistical Office (GUS) data indicates that in the last decade, the number of the employed has been steadily rising: in 2005, it was 12,890.7, whereas in 2016 the number reached 15,293.3. In the analysed period, there is a clearly visible upward trend in employment in the private sector, while there is a slight decline in the public sector.

The private sector is ideal for creative people with initiative, who are able to push themselves forward. There are great career opportunities for development and promotion, earnings are unlimited, but employees must have very high qualifications, skills or education; however, at present, it seems that education is not as important as actual skills. The private sector comes with the full package of advantages (above) and disadvantages. With regard to the latter, the primary factor is the lack of stability in employment. A private employer, although establishing an employment relationship on the basis of an indefinite duration employment contract, can effectively terminate the contract for any reason, as it is the employer who determines who he wants to work with. Lack of stability is equal to job insecurity, which translates to psychological discomfort for employees because it is the market that decides the current employment levels in given sectors at any given time.

There is a lot of competition in the private sector, which requires employees to constantly prove themselves and show creativity and initiative. They are burdened with new responsibilities and expected to constantly train and educate. These severe circumstances are frequently the cause of tension and stress, which consequently results in burnout over time. It should be also remembered that the private employer will look to pay the employee as little as possible, while expecting them to carry out as much work as possible; in comparison, state employers work with limited budget resources, and yet show more extensive care about their employees. The private employer often pays lower wages particularly in times of an economic slow-down, which means that the unemployment rates increase, and so do the numbers of candidates for the job who are willing to work for lower rates. Private employers often prefer unfavourable forms of employment, typically in the form of civil law contracts, so as not to pay national insurance contributions and not to be liable for the employee; on the other hand, the private employer keeps a detailed account of the employees’ work and demands that the tasks be performed up to standard, which is an additional source of stress and anxiety.

Work in the state administration entails privileges but also duties; still, it appears that the privileges overweigh the drawbacks. jobs in the public sector have become more prestigious and desirable, thus unattainable. Work in the public sector is also inaccessible due to prevailing nepotism; it is believed that work in the public administration is available exclusively for those who have backing. As a result, convinced of its futility, many may not even make an effort to apply. Unavailability of work in the public sector also results from the economic crisis. The crisis has made millions aware of the importance of job security and convenient forms of employment, which is what the public sphere offers.

The work in the public sector will typically require comprehensive education and general knowledge. On the other hand, through employment, the state takes the employee under its wings, and sometimes provides further education opportunities and provides them with prospects for development and promotion. Such an employer is particularly suitable for largely passive people with little initiative or lacking the force of penetration. It is often claimed that working in the state sector is less profitable. however, this appears to be a case of over-generalisation as earnings in the public and private sectors are comparable. In fact, it may emerge that the earnings in the public sector may be even higher, as the average remuneration frequently does not account for the large discrepancy between the levels of earnings in senior management or top management who, in the case of private business, earn large amounts of money. On the flipside of high earnings in the private sector, there are the employees of food discount stores, who earn a minimum salary, are employed on civil law contracts, and whose situation and working conditions are far worse than in the public sector. An additional positive aspect of working in the public sector is that specialist knowledge is rarely required of new employees, as is often the case with private sector employment, where broad knowledge or qualifications are required of candidates for even the lowest positions.

Poland is a country where a process of democratisation began in 1989, and thus the process of moving away from socialism to capitalism and the free market. This type of approach meant that Polish society began to diversify and social stratification ensued. today, several social classes can be distinguished, which constitute a layered structure of Poland. The basic social classes, covered in the preceding sections, can be classified as the upper, middle, lower and underclass.

The upper class is the rich and highly qualified, very often big entrepreneurs, members of the government, top government or local government officials, etc. They are simply specialists and experts in a given field, which earns them comfortably high earnings and high financial status. This group should not be considered as potential candidates for military service.

The middle class denotes medium and small entrepreneurs, owners of shops and factories, as well as specialists working on a full-time basis for an average national wage. Another class is the lower class. These may be individual farmers who run small farms but also the unemployed, unskilled, and unqualified labourers. It seems that the offer of employment in the armed forces should be directed to the latter two.

The last class is the underclass, these are usually people from the social lowlands, living on the margins of society, who are unable to find their place in the society, are at the very bottom of the social ladder, and live in extreme poverty and undernourishment. Very often, they are people who live in conflict with the law and who do not want to develop in the social structure of Poland.

The stratified structure of society is a concept classifying and explaining the position of individual people in the society, coined by a sociologist Max Weber. Sociology has separated several layers to show social diversity. The layered structure, much as the Marxist classification of classes, lists the differences that occur in society within individual units coexisting with each other. The arrangement and division of social classes in Poland is constantly changing as a result of technological development, an increase in the level of education and an increase in social awareness.

At this point, it should be remembered that the increase in the level of education is one of the key factors determining the progress of society. Data presented by the Polish Central Statistical Office (GUS) indicates that the level of education of Poles is constantly increasing. In the fourth quarter of 2016, the number of graduates in higher education reached 7,122, 4,323 of whom were women. The levels exhibited an increase by approx. 200,000 compared to the preceding year; the rise was observed for both men and women. Simultaneously, the figures for men in higher education in 2015 and 2016 did not change, i.e. remained at a level of approx. 2,890. Considering the minimum qualification requirements for particular military personnel corps, this is the group to explore in a search for potential candidates for the commissioned officer corps. As was mentioned in previous sections, professional officers serve on either a permanent or contractual basis, having obtained the professional Master’s degree or equivalent. Obviously, the main source of recruitment to the officers’ corps are graduates of military universities, which educate candidates for professional soldiers. Currently, there are four such institutions, i.e. General tadeusz Kościuszko Military University of Land Forces, Polish Naval Academy, Military University of technology and Polish Air Force Academy. The universities are approached predominantly by secondary school graduates, who, upon successful graduation, hold a Master’s degree following a 5-year training. An additional source of enrolment candidates are graduates of Officer Candidate Schools, which educate future officers in specialties not trained in Master’s studies at military universities. Owing to the fact that the course is shorter, this allows an on-going response to personnel needs in all military specialties.

Recruitment for military training as part of the Officer Candidate School at military campuses is conducted among holders of a Master’s degree or equivalent, including: non-professional-military university graduates in courses compatible with a given corps, non-commissioned officers who are graduates of faculties of studies in demand from a specific personnel corps or with experience and qualifications in a specialty useful in a specific corps, professional privates – graduates of faculties useful in a specific corps, graduates of national medical schools. Therefore, the growing interest in obtaining higher education, seen in society seems to be highly beneficial for the armed forces; however, considering the gender structure in the armed forces, it would be more beneficial for men, especially those with technical inclinations, to show a further-reaching interest in higher education.

The percentage of the population with secondary education remains consistent and amounts to approx. 10,300. As far as the education profile is concerned, it is relatively similar among women and men in postsecondary and secondary vocational education (3,688 thousand women and 3,571 men), secondary comprehensive education is the level reached by 800 thousand women more than men, i.e. 1,937. This social group may apply for an appointment in the non-commissioned officer corps of the armed forces, where the minimum level of education is secondary or secondary trade education. Currently, the training for candidates for non-commissioned officers is present in two forms. Firstly, there is the training within the Non-Commissioned Officers School for non-military candidates, which provides education in a limited scope, i.e. for orchestra members in the Army Musical bands, as well as for the needs of the territorial Defence Forces. The other form of education is the training of professional privates with secondary education, which currently constitutes the main source of recruitment to the non-commissioned officer corps, at the same time enabling professional development of outstanding recruits for higher professional ranks. At present, there are five Non-commissioned Officers Schools in the armed forces, at: the Military University of Land Forces, the Polish Air Force Academy in Dęblin and Koszalin, the Polish Naval Academy and the Military Medical training Centre.

According to the data provided by the Polish Central Statistical Office (GUS), the share of people with primary vocational, primary and incomplete primary education has decreased. According to the 2016 data, the number of people with only basic qualifications was about 13,000, whereas for the sake of comparison, it decreased by about 600,000 citizens in 2015. For this social group, the armed forces offer service in the rank of professional privates. The professional military service appoints candidate service soldiers, graduates of lower secondary, vocational or trade schools, who have completed military training in a training centre or reserve soldiers in the military rank of private or private 1st class who have finished active military service, have lower secondary or vocational education and professional qualifications or skills useful in the corps in which they are to perform the professional military service.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the educational level of the population has a large impact on the military manpower, particularly at lower levels (secondary school) where military training is not implemented. Military training at higher levels of education largely satisfies the personnel needs of all components of armed forces. Therefore, special attention should be focused on high school graduates, and the search efforts for potential candidates for military service should be focused on this particular group. This group provides human resources for both commissioned officers (upon graduating from a military college) and non-commissioned officers corps.

The manpower of the armed forces, including appropriately trained mobilisation reserve forces, must account for the emerging threats as well as the factual potential of the state. Currently, additional soldier force is in high demand not only due to the creation of Territorial Defence Forces but also to supplement the personnel count in operational units. The analysis of the dependence of the armed forces on the social structure has shown that its different elements exhibit a varying degree of impact on the military manpower. The demographic structure of Polish society is the most sensitive element of the social structure regarding the size of the armed forces. The continuing demographic slump in Poland leads to a decrease in the personnel resources in the productive age. The labour market is competing for the employee, and, as a consequence, the armed forces must also rise to the challenge. It is essential that the created employment offer is an attractive alternative in comparison with the opportunities on the market. however, simultaneous efforts are required on the part of the state to curb the demographic decline. human capital is an important factor conditioning the state security, the growth of the national economy and the efficiency of the state.

Undoubtedly, withdrawing the restriction that formerly prevented contracted soldiers from obtaining pension entitlements was a step in a good direction. Nevertheless, at the same time, the need arises to devise employment mechanisms in the army so as to avoid scenarios in which the posts for young privates would be occupied by 50-year-olds: for understandable reasons, the military may under no circumstances become a sheltered workplace. It is certainly obvious that the requirements for soldiers should vary depending on the nature of their service – a different level of fitness is expected from a soldier in air-mobile forces, compared to the security services. Stable salary and benefits have become a tempting alternative for young people beginning their careers. Nevertheless, it seems that it is necessary to undertake more intensive recruitment activities in order to reach wider audiences of recipients. Furthermore, years of experience indicate the need for maximum simplification of the military service appointment procedures.

The level of education in society is increasing, yet it does not exert such a considerable impact on the number of armed forces personnel, which is secured by the military education system. What does pose a significant difficulty is its capacity. The ministerial decision to increase Polish military manpower was not followed by the necessary development of training opportunities for the personnel in all ranks. Furthermore, the changes have failed to account for the demographic and economic situation in Poland.