Introduction

Today’s security environment calls for a stronger and more responsive Europe. In both the East, Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine and the illegal annexation of Crimea, and the South and across the Mediterranean, Europe is facing instability running from Syria up to the Sahel region in Northern Africa (EPP 2015). These and other challenges test the ability of EU CSDP to ensure peace and stability on the European continent and in its neighborhood, to prevent threats from inside and outside. It took a while for the EU to realise the need for a strong EU defence. The implementation of new EU ideas in defence and security domains (such as PESCO, the European defence Fund (EDF) and other initiatives) may be valuable for Lithuania because of the security challenges, its geographical location and the opportunities.

Lithuania, as a member of the EU, has its own agenda in CSDP since it is sometimes challenging to align national interests with the common EU position. Agreeing on a new platform that could enable positive developments in the field of national defence and boost NATO’s overall capabilities was a priority and, at the same time, a unique opportunity for Lithuania. Negotiations that were framed mostly by initial German and French positions forced Lithuania to choose its own stand while carefully balancing own vs common interest, Lithuanian’s deeper participation in the majority of CSDP activities reinforces assumptions that the risk of US self-isolation and post-Brexit are high and the “EU strategic autonomy” option is the best national option for the moment.

The aim of this paper is: to acknowledge historical and current developments in the EU CSDP and analyse the interdependency between new EU initiatives in CSDP and the impact for Lithuanian national defence po`licy. To achieve this aim, the following tasks were designed:

Describe the path of EU CSDP development.

Define roles and responsibilities of EU structures that act in the EU CSDP context.

Examine current trends in EU CSDP.

Investigate the main outlines of Lithuanian national security policy and its deviations.

Analyse current Lithuanian activity in the EU CSDP and consider the national decision making aspect in terms of PESCO.

While writing this essay, the comparative scientific literature and document analysis method was used. Further data was systematised and framed in a descriptive way. The paper is structured in two big parts. The first part is devoted to a review of EU CSDP by firstly acknowledging the historical facts of this framework, then looking at the decision making bodies and finally at the contemporary CSDP situation and outlining current developments in PESCO. The second part is committed to analyzing the Lithuanian context in EU CSDP, by firstly examining the National Security Strategy, current Lithuanian activities in EU CSDP in the military and civilian domain, and lastly providing a short analysis and insights on current Lithuanian involvement in PESCO. Special focus is given to national decision making aspects and current policy deviation. The main findings are listed at the end.

EU CSDP

The roots of EU CSDP

The concept of a common defence policy in Europe dates back to 1948 when the United Kingdom, France, and the Benelux countries signed the Treaty on Economic, Social and Cultural Collaboration and Collective Self-Defence, also known as the Treaty of Brussels. The agreement included a mutual defence paragraph that later facilitated the creation of the Western European Union (WEU) which remained until the late 1990s. Following the end of the Cold War and conflicts in the Balkans, the EU assumed an enhanced role in the field of conflict prevention and crisis management (Márquez Carrasco et al. 2016, p. 17). The already established forum served as a foundation for the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) introduced in the Maastricht Treaty in 1993. The Maastricht Treaty states that the CFSP comprises all questions related to the security of the Union, including the framing of a common defence policy (Márquez Carrasco et al. 2016, p. 18). The Petersburg tasks agreed at the WEU Council meeting in Germany 1992 were incorporated into the Treaty of Amsterdam defining military actions and functions that the EU can undertake in its operations (humanitarian and rescue tasks, peacekeeping tasks, tasks of combat forces in crisis management, including peacemaking) (Churruca 2000, p. 206, Koutrakos 2013, p. 31). Before the Amsterdam Treaty was ratified on 1 May 2000, the Cologne European Council of 4-5 June 1999 strengthened the CFSP through the development of a military crisis management capability. With this aim, the EU Member States decided to build a Common European Security and Defencse Policy (CESDP) backed by credible military forces and appropriate decision-making structures (Koutrakos 2013, p. 32). Another key development was the adoption of the Berlin plus Agreement which gave the EU, under certain conditions, access to NATO assets and capabilities (Rehrl, Weisserth 2012, p. 15). The European Council meeting in Santa Maria Da Feira in 2000 reaffirmed “its commitment to building a CESDP capable of reinforcing the Union’s external action through the development of a military crisis management capability as well as a civilian one” (Council of the European Union 2000). In 2003, the first European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP) mission was launched in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Shortly after, in December 2003, the European Security Strategy (ESS) was formulated. This was a landmark in the development of the EU’s foreign and security policy, as the EU, for the first time, agreed on a joint threat assessment and set clear objectives for advancing its security interests (Solana 2003, p. 56). With the ratification of the Lisbon Treaty on 1 December 2009, the ESDP was renamed as the CSDP. The Lisbon Treaty was a cornerstone in the development of the CSDP, while incorporating in the Treaty the notion of political and military solidarity among EU Member States via the inclusion of a mutual assistance clause in Article 42 (7) Treaty on the European Union (TEU) and a “solidarity clause” in Article 222 TEU. Responsibility for guidance on the CSDP was transferred from the rotating presidencies of the Council of the EU to the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and the Vice-President of the European Commission (HR/VP), supported by the European External Action Service (EEAS) (Whitman and Juncos 2009, p. 40).

Roles and responsibilities of EU structures in connection with CSDP

Decisions relating to the CSDP are taken by the European Council and the Council of EU. They are taken by unanimity, with some notable exceptions relating to the European Defence Agency (EDA) and PESCO. Proposals for decisions are normally made by the HR/VP. Twice a year, Parliament holds debates on progress in implementing the CFSP and the CSDP, and adopts reports: one on the CFSP, drafted by the Committee on Foreign Affairs; and one on the CSDP, drafted by the Subcommittee on Security and Defence (European Parlament 2017, p. 1-2). The HR/VP occupies the central institutional role, chairing the Foreign Affairs Council in its “Defence Ministers configuration“ (the EU’s CSDP decision-making body) and directing the EDA. Parliament examines developments in the CSDP in terms of institutions, capabilities and operations, and ensures that security and defence issues respond to concerns expressed by the EU’s citizens. Following the HR/VP’s 2010 declaration on political accountability, Parliament participates in Joint Consultation Meetings held on a regular basis to exchange information with the Council, the EEAS and the Commission (European Parlament 2017, p. 3).

The list of EU instruments to project stability is long: development co-operation; external assistance; economic co-operation; trade policy instruments; humanitarian aid; social policies; environmental policies; diplomatic instruments (political dialogue, mediation); economic or other sanctions (Márquez Carrasco et al. 2016, p. 30). The European Commission and the various European agencies may also be engaged in the crisis management with active support from the EEAS, the EU Special Representatives in priority regions and a network of over 140 EU delegations around the world (Pirozzi 2013, p. 12). The EU is in a unique position to make different contributions to complex crisis management situations as it has a broad range of political, economic, civilian and military instruments at its disposal. The full range of instruments provides the EU with a unique external capacity, but all the lines of action taken by the players involved with the need to ensure proper coordination.

EU CSDP in action. How does it work?

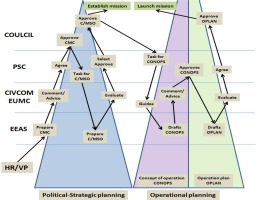

Assessments and reports carried out within the EEAS and the European Commission are valuable sources for assessing new or ongoing CSDP missions or operations. Within the EEAS, the EU Military Staff (EUMS) serves as a coordinating platform for Member States’ military intelligence, while the EU Intelligence Analysis Centre (EU INTCEN) handles Member States’ civilian intelligence. The periodic reports issued by the Heads of Mission or Delegation constitute valuable sources of information (Márquez Carrasco et al. 2016, p. 87). In the case of existing crisis situations, at the request of the UN or the initiative of one of the Member States, the Commission, the HR/VP and Political and Security Committee (PSC) will discuss whether, and in what way, the EU could contribute to stabilising the situation. The PSC requests advice from Council Working Groups, while a joint fact finding mission of the Council Secretariat and the European Commission is deployed to provide recommendations on potential risks and the most appropriate form of action. EU INTCEN reports on the situation on a daily basis, while military and civilian personnel at the Council Secretariat work on the strategic planning of the CSDP operation. The Crisis Management Planning Directorate within the Council Secretariat is tasked with drafting the Crisis Management Concept (CMC). Simultaneously to the drafting of the CMC, the PSC asks the Committee for Civilian Aspects of Crisis Management (CIVCOM) to develop Police Strategic Options and Civilian Strategic Options. It also requests that the EU Military Committee (EUMC) develop Military Strategic Options (Schematic is outlined in Figure 1). The PSC evaluates all these strategic options taking into account the Commission’s view. Later, the PSC agrees upon the final CMC to be forwarded to the Council of Ministers for approval. All EU CSDP missions and operations are established by the Council of the EU acting unanimously under Article 42 TEU (Márquez Carrasco et al. 2016, p. 88-89). The Council adopts two formal decisions. The first establishes a mission or operation on the basis of the CMC which marks the beginning of the planning phase. The second decision, for launching the mission or operation, is adopted once the planning and force generation of the missions or operations have been concluded (Mattelaer 2010, p. 6).

Figure 1

EU Decision making process (Churruca 2000, Lintern 2017, Márquez Carrasco et al. 2016, Mattelaer 2010)

The European Council defines the general political direction and priorities of the EU and agrees unanimously on common strategies that set the objectives, duration and means for EU crisis management. The Council of the EU, in its configuration as the “Foreign Affairs Council” (FAC), is chaired by the HR/VP instead of the EU presidencies. Member States’ ambassadors meet in the Committee of the Permanent Representatives, which deals with institutional, legal and budgetary aspects of CFSP/ CSDP and prepares the Council Decisions to launch CSDP missions and operations (Márquez Carrasco et al. 2016, p. 93).

The EUMC is the highest military body within the Council and it is composed of the chiefs of defence of the EU Member States, who are regularly represented by their permanent military representatives. The EUMC provides military advice and recommendations to the PSC and monitors the proper execution of the military missions and operations. EUMS, under the direction of the EUMC, coordinates military operations and missions requiring military support and the creation of military capability (Kirchner 2006, p. 949). The Politico-Military Group carries out preparatory work in the field of CSDP for the PSC which covers political aspects of EU military and civil-military issues. The CIVCOM is a consultative body composed of national representatives and officials from the Commission and the Council Secretariat. CIVCOM formulates recommendations and gives advice to the PSC on civilian aspects of crisis management (Bantas 2015, p. 240).

The European Commission is responsible for administering the CFSP budget and cooperates with the Council in decision-making in order to promote coherence and synergies between CSDP operations and the activities of the Commission. The relationship between the EEAS and the Commission is crucial to implement security-related programmes. The Member States remain central to EU CSDP, they take the ultimate decision to launch and extend the mandate of CSDP missions and operations. As noted above, the main decision-making organs within the Council are composed of EU Member States representatives. However, the main challenge arises from the fact that EU Member States do not share the same vision in the areas of defence and security, and CSDP is not equally supported by all. National Parliaments and civil society organisations play a modest role in the making of CSPD. The parliamentary control mechanisms over foreign policy differ from one Member State to another. Most Member States’ national parliaments carry certain political weight in overseeing and shaping foreign policy including CFSP/CSDP decision-making processes (Márquez Carrasco et al. 2016, p. 96-97). The European Parliament has a limited role in the framework of CFSP/CSDP, and is restricted to being regularly informed on the development of foreign and security policy. The Treaty has mandated the HR/VP to “regularly consult” the European Parliament on the main aspects and basic choices of common foreign and security policy, CSDP and informs it of how those policies evolve (Thym 2006, p. 113). This part provides details on the processes and procedures that are established within the EU to enable external action or activity via the CSDP format. Different nations have different understandings on the situation and required action that could be implemented, and they definitely have a word to say in different established forums. Different EU structures execute different actions in operation planning and execution processes and make sure that wills of the nations are best reflected, and all future actions will be implemented with the support of all EU member states.

Current developments in EU Common security and defence policy

Over the course of the last decade, the EU has acquired an operational capability enabling it to deploy military and civilian crisis management missions in pursuit of its foreign and security policy. To date, the EU had launched 34 operations and missions, 10 of which were military, 23 civilian, and one mixed civil-military mission. Among all the 34 CSDP missions and operations there are 10 military operations1, nine assistance/supporting missions2, six police operations3, three rule of law missions4, three border missions5, and two monitoring missions6 (EEAS 2017, p. 11). EU missions and operations take different forms: civilian missions can be classified as strengthening missions, monitoring missions and executive missions; military CSDP operations are generally labelled as training or advisory operations. Only EUFOR RCA has deployed combat units in an executive operation. EU military operations tend to be oriented towards cooperation with the UN or based on formal invitation from the local authorities, not meaning that they act against UN guidelines and mandates (Márquez Carrasco et al. 2016, p. 33-35).

The Global Strategy (EUGS) for the EU’s Foreign and Security Policy was presented to the European Council on 28 June 2016. With its emphasis on security, its ambition for strategic autonomy and its pragmatic approach to Europe’s environment, the EUGS signifies an important change of philosophy from the 2003 European Security Strategy. The new strategy identifies the following priorities:

The security of the Union.

State and societal resilience to the East and South of the EU.

The development of an integrated approach to conflicts.

Cooperative regional orders.

Global governance for the 21st century (European Parlament 2017, p. 3).

In order to give effect to the new strategy, the EU is revising existing strategies and arranging new thematic or geographical strategies in line with the EUGS’s priorities. Member States welcomed the EUGS, and, in July 2016, stated their readiness to continue the work in the implementation phase. To ensure a solid follow-up, the implementation of the EUGS will be reviewed annually in consultation with the Council, the Commission and the European Parliament (European Parlament 2017, p. 3). On 14 November 2016, the Council was presented with an “Implementation Plan on Security and Defence” that sets out 13 proposals which encompass a coordinated annual review of defence spending, a better EU rapid response, including through the use of EU Battle groups, and a new PESCO for those Member States willing to undertake higher commitments on security and defence. In December 2016, the European Council endorsed the Implementation Plan. The Council conclusions called on the HR/VP to present concrete proposals on the development of civilian and military capabilities, on the Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD), on the establishment of a permanent operational planning and conduct capability at the strategic level, on PESCO, and on the EU’s rapid response tools (European Parlament 2017, p. 3).

Current developments in EU PESCO

During a speech in Prague in June 2017, Juncker referred to PESCO as the “Sleeping beauty of the Lisbon treaty” (European Commission and Juncker 2017, p. 7). Indeed, the use of PESCO has been discussed many times, but the member states failed to agree on criteria and modalities. Current PESCO focused to:

Cooperate on military investments.

Bring defence apparatus into line with each other.

Make forces more interoperable, flexible and deployable.

Cooperate on capability development.

Develop major joint equipment programmes (Koenig and Walter-Franke 2017, p. 11).

EUGS re-launched the debate on PESCO by calling on the member states to “make full use of the Lisbon Treaty’s potential”. The French and German Defence Ministers took this call up in their joint paper of September 2016 and advocated a voluntary, inclusive and open PESCO creating binding commitment on clear goals and benchmarks. In June 2017, the European Council agreed on the need to launch an “inclusive and ambitious” PESCO “with a view to the most demanding missions”. The member states committed to drawing up a list of criteria and common commitments within three months, including a precise timetable and specific assessment mechanisms (Koenig and Walter-Franke 2017, p. 11).

On 13 November 2017, 23 EU Member States signed a joint notification addressed to the FAC and HR/VP on their intention to participate in PESCO7. On 11 December 2017, (after Ireland and Portugal joined in) 25 Member States8 agreed to “ambitious and more binding common commitments” and issued an initial list of 17 PESCO defence projects to fill the EU’s strategic capability gaps. On 6 March 2018, the Council – meeting for the first time ever in the PESCO format – formally adopted the list of projects to be developed (Lazarou and Friede 2018, p. 1):

European Medical Command.

European Secure Software defined Radio.

Network of Logistic Hubs in Europe and Support to Operations.

Military Mobility.

EU Training Mission Competence Centre.

European Training Certification Centre for European Armies.

Energy Operational Function.

Deployable Military Disaster Relief Capability Package.

Maritime (semi-) Autonomous Systems for Mine Countermeasures.

Harbour & Maritime Surveillance and Protection.

Upgrade of Maritime Surveillance.

Cyber Threats and Incident Response Information Sharing Platform.

Cyber Rapid Response Teams and Mutual Assistance in Cyber Security.

Strategic Command and Control System for CSDP Missions and Operations.

Armored Infantry Fighting Vehicle / Amphibious Assault Vehicle / Light Armored Vehicle.

Indirect Fire Support.

EUFOR Crisis Response Operation Core (Council of the European Union 2018).

At the same time, the Commission’s launched EDF on 7 June 2017 aims at enhancing member state investment and fostering cooperation through three elements:

Research: From 2020, the EU will spend €500 million from the EU budget to fully and directly fund collaborative defence research.

Development: The Commission will provide €500 million in 2019 and €1 billion from 2020 to co-finance (20%) the development phase of collaborative projects between at least three companies in at least two member states.

Procurement: A condition for co-financing in the development phase is sufficient member state commitment to procure the final product in a coordinated manner (Koenig and Walter-Franke 2017, p. 13).

Launching projects requires participating states to invest. Integrating forces requires them to bring capabilities to the table. Hence the need for binding commitments is required, to ensure that everybody contributes a fair share, and continues to do so over time (Biscop 2017, p. 3). Participating member states also commit to providing “substantial support with means and capabilities” to every CSDP operation. The Council launches operations by unanimity, of course, but no member state that is in PESCO should vote for an operation and then decline to take part in it. Or, if it does not possess any relevant capability, to co-fund it. Once enacted by the Council, these commitments will be not just politically but legally binding as well, unlike NATO’s Wales’s pledge. A proposal for a governance mechanism is on the table, including sanctions for non-compliance, which indicates that PESCO is becoming equally successful. For those joining PESCO, CARD can be an important assessment tool (Biscop 2017, p. 3). A trial run started in autumn 2017 with all member states. Full CARD implementation is supposed to be built up incrementally until autumn 2019 (Koenig and Walter-Franke 2017, p. 14).

Important points that were brought forward by EU leaders in different formats to inform citizens and national decision makers about the need for Europeans to take more responsibility for their own security. This also was outlined in different EU documents and agreements. The contemporary situation shows that closer defence cooperation among EU Member States is now at the top of the agenda. The aim is to make European defence spending more efficient, and work towards a strategically autonomous European defence union. The launch of PESCO in December 2017 is also seen as a crucial step in that direction, despite some doubts regarding the success of this initiative. The PESCO project illustrates that the EU is becoming more united and less fragile, while interests for common security are on the agenda again and that supported the launching of this contemporary initiative. This positively enables movement towards a conceptual European Army ambition that could be influenced by different perceptions of separate nations participating in this initiative talking at the practical level.

Since Brexit remains unclear, the impact on PESCO is only evaluated. The UK, as the biggest military spender and possessing nuclear arsenal and capabilities to launch deployable military operations, is critical for Europe’s security. The absence of the UK will make France a stronger nation amongst PESCO participants, not neglecting the fact that 3rd parties (after Brexit - UK) could continue participating in the project. It is highly likely that France will try to raise the European army idea, which is in line with the German position, while distancing itself from the US to implement a self sustainable defence policy. The focus of a future EU army could shift to implementing tasks that are in line with the interests of France and Germany. If Brexit does not happen and the current US policy under Trump is changed (isolationism), certain PESCO projects will probably sustain their momentum due to complementary supporting efforts for NATO and certain projects will be hampered due to their support for own defence industries, which are obvious competitors of the US. EU “strategic autonomy” will be compromised and discouraged.

National Security and Defence Policy of Lithuania in connection with EU CSDP

Main outlines of National security and defence policy, national activities in the context of EU CSDP

On 17 January 2017, the Seimas of Lithuania approved the National Security Strategy (NSS) which informs and reaffirms that the national security policy (NSP) of Lithuania is an integral part of the security of NATO and the EU. NSS foresees the strengthening of EU solidarity as one of the NSP priorities. The strategy identifies threats, risks and risk factors that must be given particular attention by institutions ensuring national security (Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania 2017a). Lithuania contributes to the creation of the EU’s efficient foreign policy, CSDP, supports decisions that are based on international law and reflect the EU’s common security interests through its participation in the activities of the EEAS and contribution to the development of the EU’s civil and military capabilities (Ministry of Foreign Affairs the Republic of Lithuania 2017). As it is stated in its annual review of National defence Policy: “Lithuania, considering the role of NATO as the foundation for Euro-Atlantic security, supports the development of the EU CSDP providing additional security guarantees”. Lithuania backs the EU initiatives that further contribute to building military capabilities in Europe, fosters the EU role providing additional security guarantees as well as the solidarity of the EU members in the area of security and defence. From Lithuania’s point of view, these initiatives have to complement NATO efforts and remain voluntary (Ministry of National Defence Republic of Lithuania 2017, p. 21). While defining strategic priorities and the direction of Lithuanian security and defence policy in 2017, it became clear that EU CSDP provides valuable additional tools in which NATO has lower capacity and flexibility. Since Lithuanian decision makers are concerned with a “hybrid” threat scenario, CSDP provides decent support in terms of boosting defence. Cyber, information operations and economic warfare are the domains that could be successfully covered from the EU side, recognizsing their increasing tempo for the future. In more detail, these are the main directions of vital importance to Lithuania within CSDP:

Capacity to respond to hybrid threats (Lithuania supports the EU efforts to develop capabilities to recognise hybrid threats, increase national resilience as well as cyber and information security. Lithuania is a contributing nation to the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats).

Development of the EU crisis management capabilities (taking part in EU operations and EU Battle Group, which enables interoperability between the forces).

Cooperation with the Eastern Partnership countries (Lithuania advocates for European integration of Eastern Partners (especially Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova)).

Strengthening NATO and EU cooperation (in the areas of: response to hybrid threats, military operations, capabilities development, local capacity building, defence industry and research, maritime security, and cyber security) (Ministry of National Defence Republic of Lithuania 2017, p. 22).

Before looking for Lithuanian involvement in military activities, we should be aware of the Defence Minister’s position in that role: “Participation in international operations is a way to implement the Lithuanian commitment to international security […] the EU CSDP [...]. If we want to be defended, we also need to contribute to the defence of other countries and their interests. As beneficiaries, we are contributing in so far as we can and in accordance with our level of economic development, defence and military capabilities, and the current security situation in Lithuania” (Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania 2017b). This statement provides a clear indicator that Lithuanian understanding of the strong and sustaining strategic trans-Atlantic partnership is not certain anymore and requires deeper engagement in the EU CSDP framework that in practical terms means supporting other EU members’ engagements in military and civilian operations and active participation in all aspects of this framework.

To illustrate using figures, Seimas made a decision on the following participation of Lithuanian troops in international operations for 2018-20199:

EU Naval Force Operation ATALANTA for counter-piracy and fighting armed robbery at sea: up to 30 members of the military and civilian staff.

EUNAVFOR MED operation Sophia, EU’s military operation in the Southern Central Mediterranean: up to 20 members of the military and civilian staff (Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania 2017b).

As an active and responsible member of the international community, Lithuania contributes to the efforts to maintain peace and stability, preventing international and ethnic conflicts, solving frozen conflicts and the fight against international terrorism (Table 1).

Table 1

Lithuania‘s contribution to international operations (1994 – 2017) (Ministry of National Defence Republic of Lithuania 2017, p. 28)

Lithuania is also involved in the EU civilian missions and sends experts to the EU Monitoring Mission in Georgia, the EU Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo, and the EU Advisory Mission Ukraine. In addition, Lithuanians held management positions in some EU civilian missions (Ministry of Foreign Affairs the Republic of Lithuania 2017). Provided figures illustrate a shift in national defence and security policy towards wider engagement in EU military and civilian operations, which could be influenced on the one hand by decreasing requirements for troops from the NATO side, while NATO operations are shifted towards NATO’s Eastern flank to support Ukraine, and on the other hand increasing national interest in EU CSDP.

In the context of new threats, Lithuania has reoriented its involvement in international operations. Besides its role in Ukraine, Lithuania currently contributes more to international operations, training and advisory missions focused on building local defence capacity in the Middle East and Africa. Lithuania is becoming more involved in maritime operations, supporting efforts to stop illegal migration in the Mediterranean Sea and fight piracy in the Indian Ocean. By participating in the mentioned international operations, Lithuania positions itself as a competent and reliable ally while contributing to a more secure environment, diversely recognising that this cooperation could be vital if the situation deteriorates in the Baltic region and the US distances itself from Europe’s security.

Lithuanian activities in the EU PESCO context

The initial national decision to join PESCO that was initiated within the framework of the CSDP was taken in Parliament by the Committee on European Affairs, the Committee on National Security and Defence, and the Committee on Foreign Affairs of the Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania on 20 September 2017. It was stressed that “the effectiveness and value of the EU CSDP will depend on the success of the new initiatives in the area of the EU security and defence” (Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania 2017c, p. 1-2). Lithuania leads one of the 17 PESCO projects approved by EU member states: cyber rapid response force formation and mutual assistance in cyber security. 6 EU members are participants (Spain, France, Croatia, Netherlands, Romania, and Finland) in the project and 5 more EU countries are observers. As Minister of National Defence Raimundas Karoblis said: “Multinational EU cyber teams would be an entirely new capability that would reinforce response to cyber incidents” (Ministry of National Defence Republic of Lithuania 2018). A similar idea was introduced by President Dalia Grybauskaite’s adviser Nerijus Aleksiejunas, one of the authors of this initiative “Cyber security challenges go beyond the boundaries of an individual country, which is obvious not only in our region. Therefore, we propose to create cyber rapid response teams at the EU level. EU member states would appoint experts to these (teams)” (Baltictimes 2017). According to the diplomat, such teams could start working in 2018-2019. In addition to the mentioned project, Lithuania serves as a member of the Dutch-led military mobility initiative that focuses on smooth and effective removal of procedural, legal and infrastructural obstacles for quick movement of forces in Europe. “Fluent movement of military forces and equipment across inner borders of European countries is a crucial factor in ensuring expeditious response to threats in our region,” R. Karoblis said. According to the Minister, implementation of this initiative will be a shared interest of NATO and the EU. This will allow both organisations’ tools to be used for removing existing obstacles in the most effective way (Ministry of National Defence Republic of Lithuania 2018).

Once PESCO was launched and the common statement of German and French representatives was made on September 2016, it remained unclear how PESCO would work. The German approach, assuming support from the Lithuanian side, positioned PESCO within the EU CSDP context, while an alternative approach lead by French indicated PESCO as a tool for power. Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaitė said she “will block any initiatives that challenge existence of NATO” (BNS 2016). Once negotiation started, it was clear that there were two main national interests: the new EU initiative must complement NATO activities; the Lithuanian position should remain at the EU’s core. Detailed EU actions that could contribute to NATO were developed and further proposed by representatives from the President’s Office, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Defence (activities boosting NATO effectiveness; initiatives facilitating defence capabilities; actions that enable countering activities below the NATO Article 5 threshold). At the same time, national representatives were making sure that PESCO could have a variety of projects available for nations and not designed solely for big manufacturing states (Mickus 2018). Lithuania agreed with the position for possible 3rd party involvement (UK, Ukraine, US) in PESCO (Blatgé et al. 2016), but was not in line with the proposal to buy oEU defence production alone while building their own militaries. The final agreement that was reached after a consensus amongst different stakeholders was in line with national guidance.

Selected projects according to decision makers correspond the best with the capabilities of Lithuania and current threat perception. At the same time, PESCO projects fall in to NSS priority directions and facilitates aims as described in NSP. It is believed that these activities in the medium and long term will enable better cyber security and cooperation and, at the same time, will permit EU or NATO troops to reinforce the Baltic region if needed. Furthermore, it is crucial that PESCO projects do not jeopardise and block ongoing NATO, US initiatives in the Baltic region but remain complementary in boosting Lithuanian resilience and preparedness for defence.

Conclusions

The conceptual developments in common European security that have continued since 1948 were finalizsed by CSDP. CSDP remains the actual EU framework that adapts accordingly to the security and strategic environment, EU members perceived threats, and sustains notion of political and military solidarity amongst members.

EU CSDP is mature, since the structural establishment is functioning: there were more than 34 military and civilian operations conducted in the EU interest zone which were in line with the UN mandate. Established mechanisms ensure that CSDP is at best reflecting the interests of all nations. At the same time, the EU possesses different instruments in economic, political, and military domains than could be activated to face threats and support ongoing operations.

PESCO and EDF initiatives designed to boost EU nations’ military capabilities and, in the long run, to increase the competiveness of its own defence industrial base is gaining momentum. Voluntary commitment, particularly from all EU nations in PESCO, suggests positive outcomes within this framework. Foreseen sanctions for non-compliance could ensure the efficiency of overall results of this project.

The EU idea of “strategic autonomy” is definite since new initiatives in the CSDP framework are taking speed while neglecting the situation surrounding Brexit and predicted US isolationism. Changes in US and UK policy could slightly hamper current EU initiatives.

The approved National Security Strategy backs the EU initiatives that further contributes to building military capabilities in Europe, fosters the EU role in providing additional security guarantees as well as the solidarity of the EU members in the area of security and defence. It was recognised that PESCO and EDF could provide alternative resourcing and flexible response options without duplicating NATO’s efforts.

Lithuanian policies’ shift for greater engagement in CSDP is probably shaped by recognition that a strong and sustaining strategic trans-Atlantic partnership is not certain anymore, and in practical terms can be achieved with bigger engagement in EU military and civilian operations.

Lithuania is active in the joint PESCO initiative and is currently involved in two projects: cyber rapid response force formation and mutual assistance in cyber security; and the military mobility initiative. The decision for particular participation was dictated by the perceived threats, state ability and available technological base. Participation in the mentioned projects in the medium and long term could enable better national cyber security and enhance EU and NATO allies’ reinforcement deployment and access to the region.

Lithuanian participation in support of a comprehensive PESCO, in line with the initial German position, achieved the given political aims to seek wider projects (not only applicable for big nations that possess major military industries) and positioned itself was one of the core members of the EU.